The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has released a draft project list intended to go along with its mammoth Seattle Transportation Plan, still in development and set to be finalized over the coming months. The list, which includes 80 discrete ideas for projects that would overhaul segments of Seattle’s street network over a long time frame, isn’t yet prioritized, doesn’t include the full scope of improvements for each mode, and doesn’t have any costs attached to it.

The list includes many of the types of projects that you’d expect a transportation levy to deliver: multimodal corridor upgrades, future RapidRide lines, upgrades to existing trails, and some concepts for new bridges. It also includes projects that build on the Seattle Transportation Plan’s “People Streets and Public Spaces” element, including a proposal to create a cafe street at Pike Place Market, and an idea for more people-oriented streets in South Lake Union.

The Center City Connector streetcar is on the list, as is Lake Washington Boulevard. So are safety-minded redesigns of Aurora Avenue N and Rainier Avenue S, two of Seattle’s deadliest streets where advocates have long demanded changes. But without scoping or a dollar figure, deciphering the extent of the improvements the Harrell administration has in mind is difficult. And in the streetcar’s case, the lack of funding to restart the project (stalled since a 2018 decision by Mayor Durkan) in the mayor’s recent budget proposal does not suggest an urgent timeline to complete the project.

The list also includes brand new projects, such as proposals for a new pedestrian and bike bridge across the Lake Washington Ship Canal, a RapidRide bus route between Capitol Hill and Beacon Hill, and Complete Streets improvements to some of the city’s most dangerous streets, like Lake City Way, 4th Avenue S, and Airport Way S.

The brand new list provides a fresh perspective on what projects could be included in Seattle’s next transportation levy, as the Harrell administration works behind the scenes to craft a follow-up to the 2015 Move Seattle levy, which is expiring next year. Move Seattle included several high-profile, flagship projects called out directly in campaign literature: a replacement of South Lake Union’s Fairview Avenue Bridge, the Lander Street railroad overpass in SoDo, as well as some projects that faltered like Accessible Mount Baker and Graham Street’s infill light rail station in Sound Transit’s control. Those delayed projects now find themselves on the project list.

Getting a handle on which projects might get tackled first will be one way to ensure that no ground is lost in the transition from one levy to another. A major selling point for a transportation levy is the opportunity to leverage funds for federal grants that just wouldn’t be available without the local funds to match, but SDOT is in an awkward position right now, and lacks the ability to put up local matching dollars that could potentially be included in any levy approved in 2024.

The Seattle Transportation Plan as a whole has been subjected to criticism, including from the Seattle’s Planning Commission, that it doesn’t contain enough details on how the ambitious vision laid out in the plan will actually become reality. The project list does provide some concrete proposals that SDOT is advancing, but implementing the projects on the list, and ensuring it doesn’t just sit on a shelf, is another question.

The Urbanist chatted with SDOT’s Jonathan Lewis, one of the department’s project managers on the Seattle Transportation Plan, about how the project list came out of the work on that plan. “This list, it has 80 projects, and quite frankly, we probably couldn’t afford to do all 80 of these over the 20 years,” he said. “And that was intentional because we wanted the community to help us in refining this.”

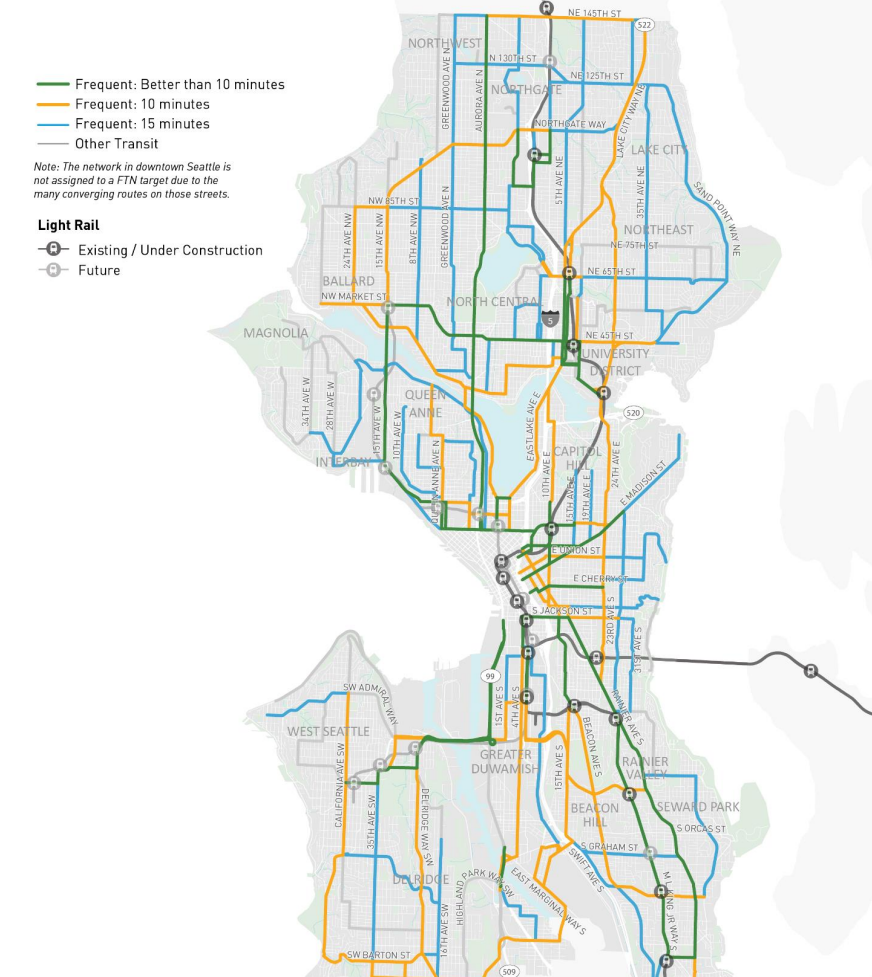

Lewis explained the full project list came from previous lists that had been developed as part of the city’s existing modal plans, like the 2015 Transit Master Plan, with safety data that is informing SDOT’s forthcoming Vision Zero implementation plan — showing corridors on the city’s high-crash network or areas with a significant history of bicycle and pedestrian crashes.

The list was also informed by the growth strategies envisioned as part of the update to Seattle’s comprehensive plan. On account of growth, the city expects to accommodate an additional 800,000 additional transportation trips per day, most of which will need to be accommodated via walking, biking or taking transit. Many corridor projects in the list are in areas where those trips are anticipated by laying future network maps for each mode on top of each other. “Bringing those priority networks together helped identify corridors of opportunity,” Lewis said.

The list may see future updates as SDOT completes a full analysis of pavement conditions on arterial streets, work that is wrapping up now. Streets that are in need of repaving open up opportunities for the city to implement improvements, as required by the city’s Complete Streets ordinance.

Smaller projects, which are referred to as “programmatic elements,” including individual blocks of new sidewalks, bike lanes, or bus lanes, aren’t included in this larger list but will likely make up a big part of any future levy.

Ultimately, any specific project being on the list won’t mean that specific outcomes are guaranteed, with familiar fights expected over use of street space for specific modes and any change in the use of current street space taken up by parking.

“We say in the [Seattle Transportation] plan and in the comp plan, and this has been the case for a very long time, that our priority investment networks are higher policy priorities over curbside parking,” Lewis said. “But you know, that’s controversial, and that will, I imagine, continue to be controversial. So we have a strong policy framework for that shift. But that doesn’t negate people’s ability to weigh in on that.”

Decisions on which projects should be prioritized first, and included in the next levy, will likely be made in Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell’s office. So how is development of that levy going? We know that the Harrell administration is holding regular meetings with transportation and climate advocacy organizations, with Deputy Mayor Adiam Emery, a former division head at SDOT, taking the lead on the issue. So far, there are no concrete proposals that have been released to the public.

At a groundbreaking earlier this month, in response to a question about the next levy from The Urbanist, Mayor Bruce Harrell said the City was “aggressively and thoroughly and urgently, but not haphazardly, looking at the conceptual foundations for the new levy… looking at our projects, where we need to pick up the pace, where we’re capable of picking up the pace. Again, to do it without compromising the quality of the projects, or the core foundation, which is safety.”

Harrell also gave a nod to environmental sustainability and maintenance needs.

“Using the cornerstones of what I call the 3 S’s, safety, sustainability, and structural integrity — making sure we’re maintaining our current assets — using that as a sort of conceptual framework, we’re looking at this levy,” Harrell said. “I think the voters have an appetite for a strong, safe transportation system.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.