An appeal brought by neighbors threatens to delay construction and heap costs on cash-strapped Seattle Public Schools.

Construction on a new Alki Elementary School in West Seattle has stalled. The former school, demolished this summer and now a vacant lot, sits quiet, with the process to issue a permit to start construction on a new school stalled after an appeal of the project was filed this spring. At issue is a small number of parking stalls, with Seattle Public Schools set to take the issue to King County Superior Court this week. Even in a best-case scenario, the ordeal looks to add substantial delays — and costs — to a project that is supposed to open by the fall of 2025.

Seattle Schools’ design for a new Alki Elementary includes no off-street parking. That design is fairly well-aligned with decades of school construction in Seattle, including recent schools and older schools built in the 1950s and 60s. Most of the parcels where schools are built, directly in the middle of built-out residential neighborhoods, don’t include enough land for off-street parking and the city’s transportation department has encouraged walking and biking to schools rather than driving.

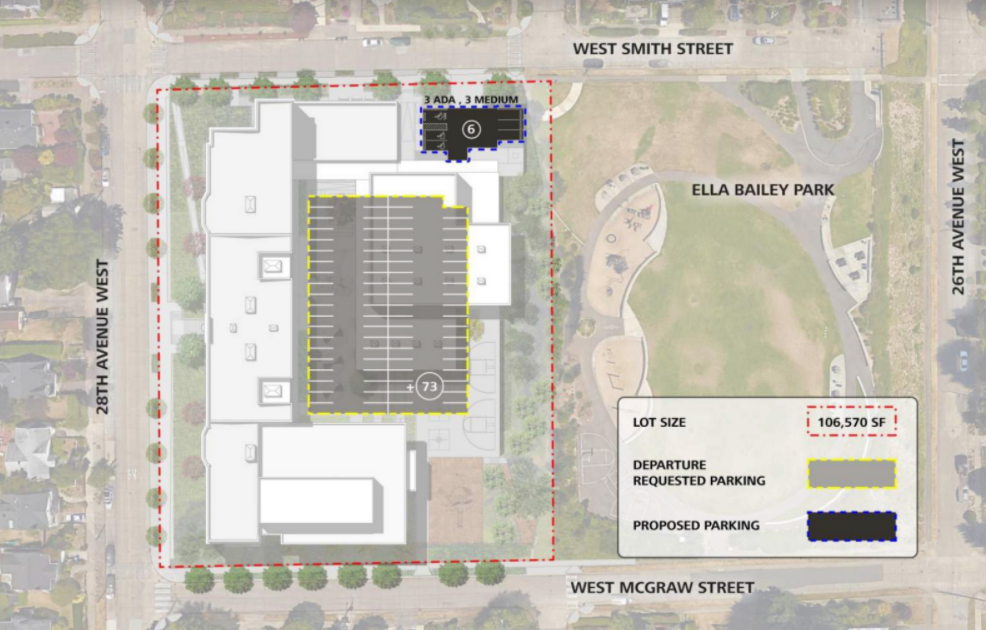

Yet Seattle’s land use code still includes minimum parking requirements, a certain number of stalls based on the amount of new assembly space being added — not classroom space. At Alki, this would mean 48 off-street stalls, an amount that would take over the small site, or require an expensive underground garage.

At full capacity, the new building at Alki Elementary is intended to serve around 500 students at any one time, with up to 75 staff members; the requirements for off-street parking did not stem from expected transportation needs of the students or teachers, however. While teachers are expected to make due with transit, walking, biking, or parking elsewhere, Seattle’s code assumes that would be too much to ask for members of the general public attending events at the school.

This disconnect between how Seattle Schools actually builds its buildings and the requirements on paper means the district has to apply for a “departure” from the code. Off-street parking isn’t the only area in which the district regularly has to apply for departures when constructing schools: adding HVAC systems to the roofs of buildings in residential neighborhoods also regularly requires a departure, as does the simple act of installing an electronic sign in front of a school to notify families of upcoming events. In most cases, even when an appeal adds time — and expense — to school construction, these departures are granted without much rigmarole.

Seattle’s Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) granted Seattle Schools’ request for a departure around parking at Alki this May. “Due to the limited nature of this site, providing on-site vehicular parking would result in sacrificing educational program and outdoor learning opportunities,” the approval noted. “The Director finds that the departure is appropriate in relation to the character and scale of the area.”

A number of nearby residents disagreed, and filed an appeal shortly thereafter. Many of them separately filed appeals argued that a lack of off-street parking would cause increased traffic in the neighborhood, and that Alki’s special parking overlay district, which requires more parking with residential construction than elsewhere in the city, meant the departure should not have been granted.

The appeal was not unusual, and mirrored appeals of new school buildings elsewhere in the city that have been dismissed in recent years, including for Rainier Beach High School and a new building for Montlake Elementary. Most appeals filed try to make an issue out of every departure that is sought, hoping to make one stick.

This one did. In August, the Seattle Hearing Examiner ruled that all of the other departures requested in the case of Alki, including around bicycle parking, were fine, but that the requested variance in the number of off-street parking spaces was not. In her analysis, deputy hearing examiner Susan Drummond gave substantial weight to the testimony of the appellants regarding the availability of parking on both city streets and the informal, unmarked lot that formerly existed adjacent to the former school building.

“The experiences of neighbors who live and observe street conditions daily was that the street network density and shorter block faces, coupled with the site’s unique conditions, and the removal of on-site parking, will make the situation considerably more difficult for parents dropping off their children and for circulation generally,” Drummond wrote.

In handing the issue back to SDCI, Drummond went to far as to suggest that the district could consider acquiring existing homes to the south of Alki Elementary to demolish them and make room for 48 parking stalls. “The School District did not identify underground parking as an option and while it prefers not to acquire local residences for the school, it did not detail why land acquisition is otherwise infeasible,” she wrote.

Now Seattle Public Schools is taking the matter to King County Superior Court, with an initial hearing set for this Friday, hoping to retain the design of its school building as developed by Mahlum Architects. While SDCI agreed with the decision to leave out parking at Alki, the City of Seattle argues that the decision can’t yet be appealed in court because it’s not final, and that it’s up to SDCI to provide updated guidance around the issue of parking.

That leaves Seattle Public Schools in the position of having to look at options that add some, if not all, of the required parking laid out in code. While Seattle Public Schools didn’t directly confirm that it was considering removing early learning facilities from the plans for Alki Elementary, saying only that the district is continuing to explore options, multiple sources with close ties to the district confirmed that option is on the table.

“I don’t think that we should be prioritizing cars over kids,” Seattle School Board Director Vivian Song Maritz told The Urbanist. “The choice that we have is to create 10 to 20 parking spots, or we can create space for 20 to 30 kids to have the benefits, all the academic, social, emotional benefits, from having early learning. There’s so much research that shows that when kids are prepared before they start kindergarten, they’re successful all the way through 12th grade and beyond.”

If a King County judge doesn’t force Seattle Schools to pursue that option after this week’s hearing by dismissing the case, resolving the issue could still take months, likely pushing back the construction timeline and leaving kids who would be attending Alki at a temporary school. Those delays, and added changes to building designs, add costs to a district that is already facing a significant revenue shortfall.

The larger issue being highlighted at Alki is the need to reduce code departures that result in appeals like this in the first place by reforming Seattle’s land use code to accurately reflect current educational needs. One of the loudest voices for doing just that has been Seattle’s school traffic safety committee. That committee cited a figure of $2.5 million per year from the district’s school construction budget that could be saved if the district didn’t have to apply for a laundry list of departures on every project.

“I hope that we can have a code that reflects the way Seattle physically is, and that the school district knows that they can add heating and ventilation equipment to the top of a school without a completely unknown delay period,” Margaret McCauley, a member of that committee, told The Urbanist. “And that we can manage transportation as a sort of network of getting people to and from and around, and not try to push it onto the school district, which is not, in fact a parking demand management organization … their mandate is different.” McCauley has been advocating for change in the code for many years now, authoring an op-ed on the topic in 2021.

A spokesperson for SDCI confirmed that early work is underway to revise the city’s land use code when it comes to schools, with the process currently set to take around a year. In the meantime, Seattle Public Schools is stuck with few good options when it comes to Alki Elementary.