Adding light rail, rebuilding Memorial Stadium, and keeping tenants happy through it all is the challenge before Seattle Center.

Walking around in Seattle Center and the neighborhood surrounding it, you quickly realize that one of the city’s largest pedestrian-only spaces has a lot of untapped potential.

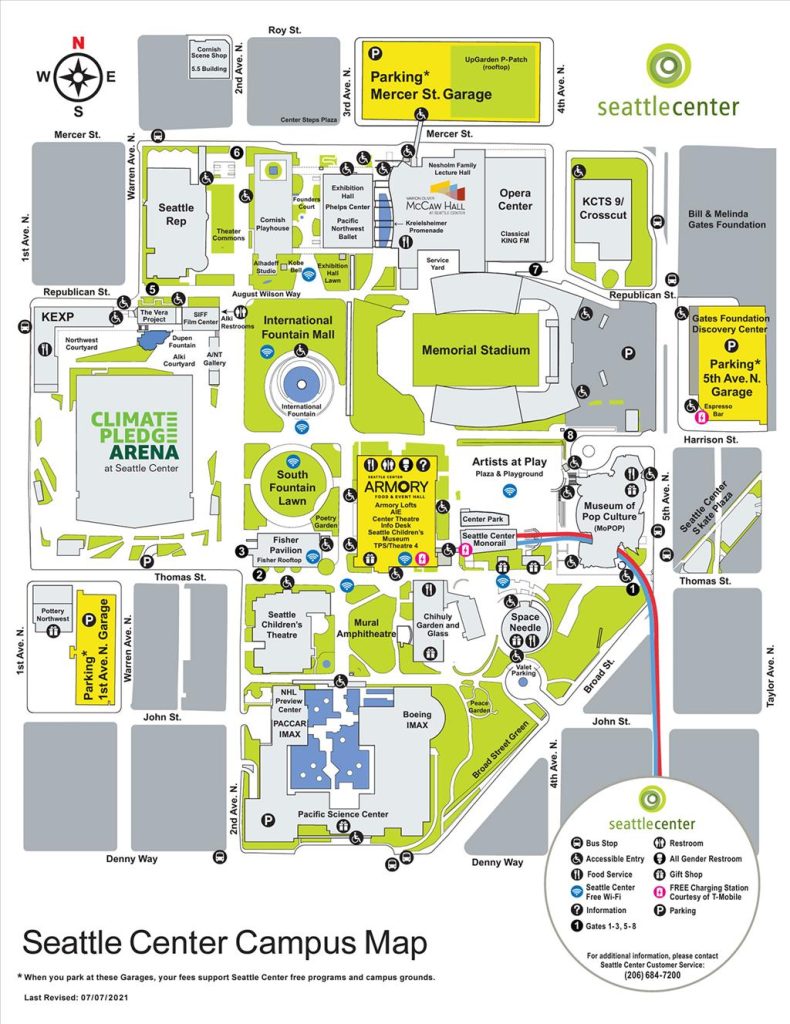

One morning in early October, I explored Seattle Center and the area around it with Debi Frausto, an activist with the Uptown Alliance, a community-based group that promotes transit, density, and pedestrian access. On an hour-long walk we examined the site of Sound Transit’s preferred alternative for the Seattle Center Link station, wandered Uptown’s sidewalks and pondered what a truly pedestrian-oriented future for Seattle Center could look like.

Near the entrance to McCaw Hall, for instance, we admired the elegant arcade that provides a refuge from the noise and traffic on Mercer Street.

“This is a nice entrance for people coming through,” Frausto said. “But where are they coming from? They’re coming from a parking garage.”

This is the strange irony of Seattle Center: The city’s artistic and cultural hub is an almost exclusively pedestrian-only space, and yet it’s also one surrounded by busy infrastructure for cars. It doesn’t help that the site, which got its start as the 1962 World’s Fair, was originally designed as a gated, ticketed space.

In the decades since the World’s Fair closed, Seattle Center has tried to become more integrated into the Uptown neighborhood – with mixed success.

“One of our big goals for this campus is that the boundaries between the edges of the community become blurred and we get more integration between them,” said Marshall Foster, the new director of Seattle Center, who was recently confirmed unanimously by the Seattle City Council on September 27.

With 17 years of experience with the City, most recently as director of the Office of the Waterfront, Foster has big ambitions for Seattle Center. In the next few years, he’ll have plenty of challenges to keep him busy, including a major renovation of Memorial Stadium, finding a new use for the KCTS building after its tenants vacate next year, updating the monorail station to ADA standards, and creating a long-term strategic plan.

In addition, the debate in the past year over Sound Transit’s proposed Link station has helped clarify what’s at stake for the neighborhood and cultural institutions on the Seattle Center campus such as KEXP, Seattle’s most renowned radio station.

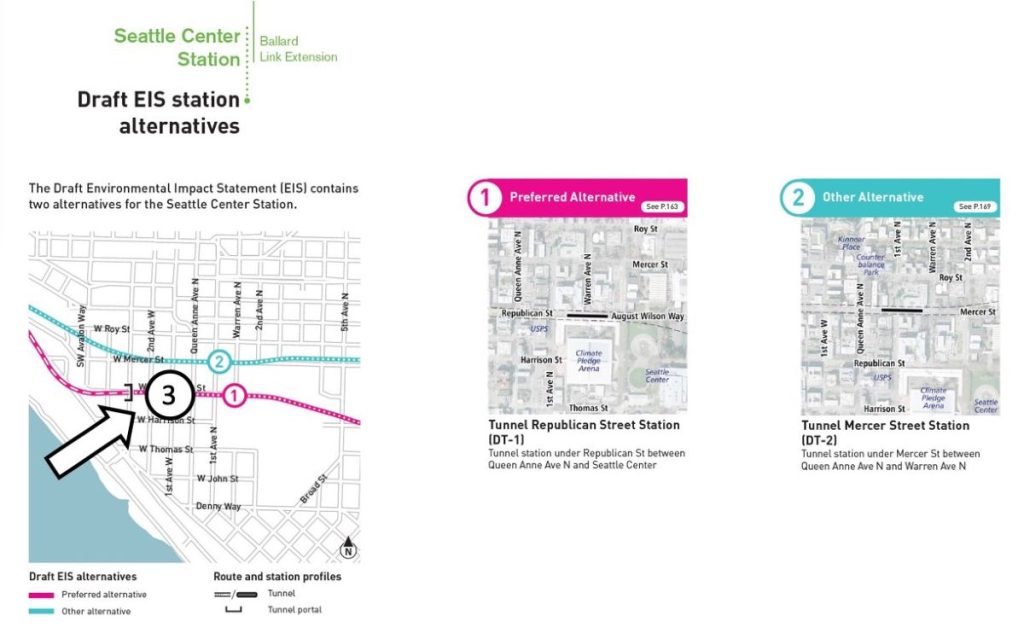

Foster says that over the past year Seattle Center forged an alliance with KEXP and the youth music and arts center, Vera Project, to express concerns about Sound Transit’s original preferred station proposal announced in January 2022, which would have been located at Republican Street between 1st and 2nd Avenue. Both KEXP and Vera Project raised alarms that construction noise and vibration would doom their current locations, and in response to a campaign of opposition, Sound Transit revised its preferred option for the station, moving it a block west to Queen Anne Avenue and 1st Avenue. The location means a longer walk for Seattle Center patrons, but tenants hope for a less disruptive construction period.

Fitting in with its focus on mitigating construction impacts across the Ballard Link line, the Harrell administration took the side of KEXP and other Seattle Center stakeholders and supported the new station alternative.

“To their credit, we actually got their attention,” Foster said. “They were willing to sit down and willing to do the hard work.”

Along with the three other late-addition station alternatives that Harrell supported for shifting Denny Station north and skipping Midtown and Chinatown, the changes to the plan mean that Sound Transit has to complete another Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS), which will take at least a year, since the new options did not exist when the original DEIS was released early in 2022.

Relatedly, Ballard Link’s targeted opening date has slipped from its initial 2035 timeline to 2039 at best according to the agency. To make up for lost time, Sound Transit has authorized preliminary engineering work to begin even as nearly half the line is being redesigned and going through the environmental study process anew.

Renovation of Memorial Stadium and an uncertain future for the KCTS building

One aging component of Seattle Center that predates the World’s Fair is Memorial Stadium, built in 1947 and owned by Seattle Public Schools. It’s been long overdue for an overhaul, and on September 27, the Seattle City Council approved a resolution designating $40 million in funds toward Seattle Public Schools’ agreement with the One Roof Partnership to redevelop the stadium into a venue supporting student sports – as well as a space for public events and concerts.

The Memorial Stadium renovation plan, announced earlier this summer, also includes $66.5 million from Seattle Public Schools’ (SPS) capital levy, as well as a commitment from the One Roof Partnership (comprised of the Kraken, Oak View Group, and the One Roof Foundation) to raise additional funds needed for the $150 million renovation.

On October 4, the Seattle Landmark Preservation Board voted to designate the memorial wall at the stadium – which honors Seattle high school graduates who died in World War II – as a historic landmark. The designation of the wall rather than the entire stadium paves the way for the renovation, which SPS says will be completed by the end of 2027.

“We’ve been trying to get this to happen for a decade,” Foster said. “It’s an unusual partner, one who wants to redevelop Memorial Stadium into a state-of-the-art community stadium. It’s not a big commercial venture like Climate Pledge [Arena].”

A surface parking lot has long disconnected the stadium from the surrounding neighborhood, and Foster is optimistic that the renovation will help transform the northeast corner of Seattle Center into a more welcoming entrance for pedestrians. “We’re very excited to begin to make it more open and porous,” he said.

Another key element in that northeast corner is the Cascade Public Media building, which serves as home to KCTS Channel 9 public television and the online news site Crosscut. With both tenants leaving in early 2024, the city-owned property will likely be used temporarily for storage and warehousing while the City considers options for the property.

Foster says the City will be deliberate in how it redevelops the site. “It’s probably our best opportunity to create a revenue stream that will support the cultural life of Seattle Center,” Foster said.

About 65% of Seattle Center’s $47 million annual budget is supported by tenants and events, while about 35% comes from the City’s general fund.

With city departments under pressure to trim their budgets, the KCTS site presents the most likely possibility to increase revenue for Seattle Center, Foster says. He notes that a hotel, market-rate housing or office/commercial space – in combination with some sort of civic or cultural use, in keeping with Seattle Center’s mission – are all on the table. “Probably not something that gives up ownership but maybe a long-term ground lease.”

One intriguing possibility that Foster says he’s open to investigating would be to include affordable housing for artists into whatever else happens with the site. This would dovetail nicely with the wide range of cultural organizations that reside at Seattle Center, including the Seattle Repertory Theater, Pacific Northwest Ballet, and Seattle Opera. It’s also a good fit with the Uptown neighborhood’s designation as one of the city’s four Arts and Cultural Districts.

“If you’ve got a band visiting to do a live performance at KEXP and they need a place to rehearse for two or three days, that’s a very hard problem to solve,” Foster said. “Or, what happens when you have a ballet company visiting for two months or three months to do performances and they have to put up 50 dancers?”

The future of light rail and and Uptown’s dense neighborhood

The year-long controversy over the proposal to site the Seattle Center/Uptown Link station adjacent to KEXP has for the most part been resolved, now that Sound Transit reworked its plan to offer as its preferred option the “Republican Shifted West” site – which is currently a Key Bank branch at Queen Anne Avenue.

Ethan Raup, the new director of KEXP, is relieved that Sound Transit moved its preferred Link station one block west of the radio station’s studios and gathering space, which has become a neighborhood hub. Raup says he still has some concerns about construction impacts and sound and vibration once the light rail station is complete, but he’s optimistic those concerns can be addressed.

“The tunneling will still cut underneath our building and so ongoing noise and vibrations from trains is a concern. But Sound Transit has a history of and the technology exists to mitigate for that, Raup said. “I feel like we’re on a pretty good path right now.”

Frausto says that the kerfuffle over the Mayor’s now defunct proposal to cut the planned South Lake Union light rail station definitely impacted thinking about how light rail will interact with Seattle Center and the Uptown neighborhood. In addition to offering transfers to Aurora Avenue buses, the South Lake Union station planned at Harrison Street will be important for serving the eastern half of Seattle Center and Uptown. That’s why the Uptown Alliance came out staunchly against abandoning the station, as some Sound Transit boardmembers like Dave Somers had pushed as a cost-cutting measure.

As we walk west on Republican past the KEXP Gathering Space, Frausto notes that some eight blocks of the street will be torn up and cross streets such as First, Second, and Fourth will be blocked during construction – impacting the neighborhood for half a decade or more.

We note the extremely narrow sidewalks at the approach to Seattle Center, which will clearly be inadequate for the crowds of people arriving for concerts, events, or hockey games. Frausto notes that the city’s lauded (but perennially delayed) Thomas Street Redefined project to improve the pedestrian approach to MoPOP and the Space Needle could be a model for this area.

“You have to ask the question: Where are there other Thomas street-like programs that we can have ready in four years?” she asks.

Foster says Seattle Center’s vision for Republican is an extensive pedestrian-forward route to and from the station, especially for times when thousands of visitors leave Climate Pledge Arena. He says that SDOT director Greg Spotts is open to that possibility. “We’d love to see Republican Street completely transformed into pedestrian use, from the moment you walk off Seattle Center’s campus to the moment you walk on the escalators down to the station.”

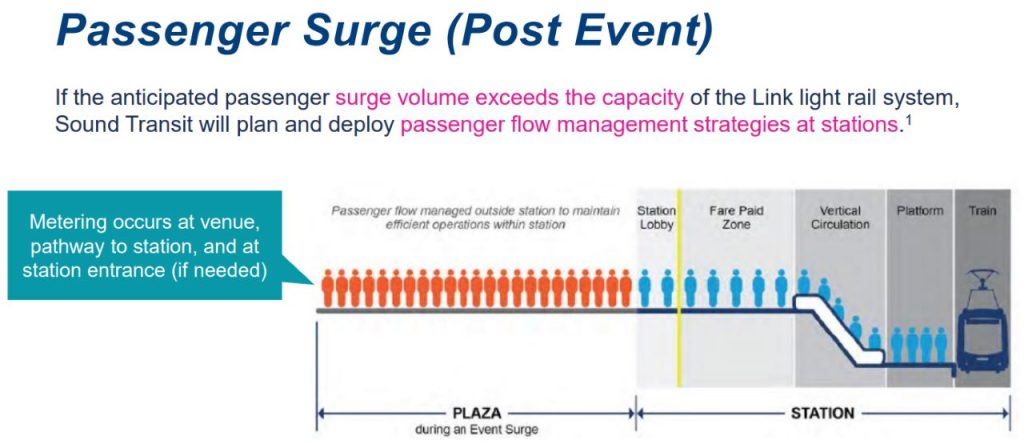

Frausto took me further west along Republican, which will be cut-and-cover construction down to Elliott Avenue. She’s concerned Sound Transit hasn’t fully considered impacts to the neighborhood during construction. She also questions whether Sound Transit has enough capacity to move people after an event at Climate Pledge lets out. “They can only move 4,800 people per hour,” she said. “That means they’ll have to queue people, hold them back.”

In another part of the neighborhood we visited the quirky P-patch community garden on the roof of a city-owned parking lot across Mercer from McCaw Hall and Seattle Rep. The building is a money-maker for the city, but Frausto wonders if it could be put to better use. She notes that Climate Pledge, by giving transit passes to ticket-holders, has far surpassed their goals for getting people out of cars.

“We need housing. We’ve got a full city,” Frausto said, looking out at the Space Needle from the roof of the garage. “Parking and revenue and all that, it’s legit. But this is an opportunity, on City-owned land, right here.”

A block over on Mercer, we walked through a lovely pedestrian pathway in a multi-use space that includes both affordable and market-rate housing – one that could be a model for the parking garage next door. Plymouth Housing’s new housing project at 200 Mercer offers 91 units of permanent supportive housing (and also features the ground floor offices of Path With Art, a nonprofit that provides healing through art for those who have experienced homelessness). In addition, the Center Steps complex offers 269 market-rate units.

Frausto notes that during a recent Sound Transit board meeting, King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci told the Uptown Alliance that her neighborhood has already embraced transit oriented development in ways that other neighborhoods near potential Link stations should be emulating.

“We have really embraced that we are an urban center,” Frausto said. “Bring us buses, bring us light rail – if it’s done well.”

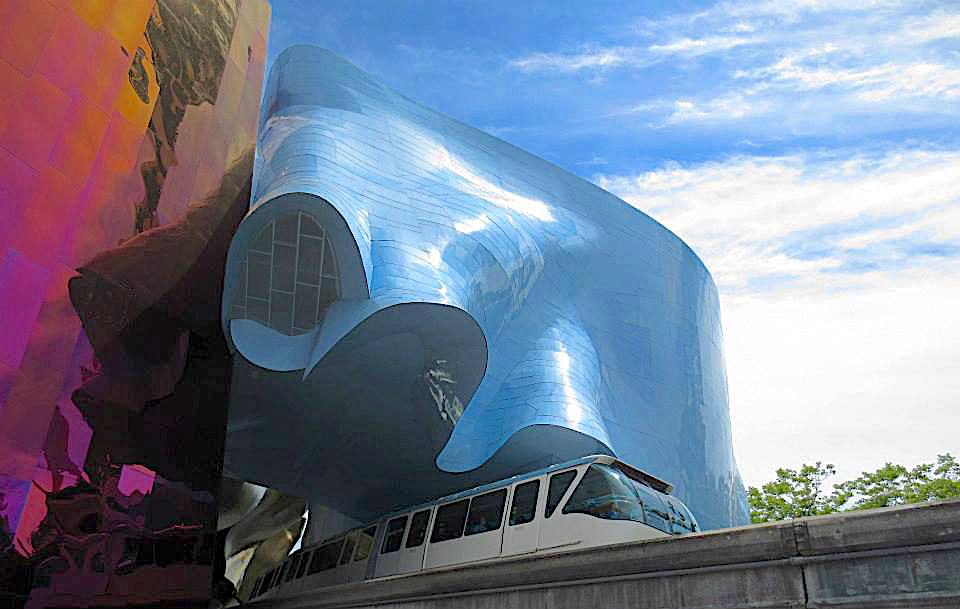

One surprisingly important transit link for Seattle Center is the 60-year-old Monorail, which provides a key connection to light rail at Westlake station. Foster notes that thanks to a $15 million federal grant the Monorail will get an upgrade to become fully ADA accessible.

Another long-term improvement Foster is especially interested in on the Seattle Center campus is substantially upgrading pedestrian infrastructure – he notes that many of the walkways that date from the original World’s Fair are asphalt. He points to the “theater commons” approach toward Seattle Rep from 2nd Avenue as a template for the rest of Seattle Center: “It has paving, high quality lighting, high quality landscaping, all done as a system,” he said. “I’d like to see if we could extend that model to the rest of the campus.”

That of course will require a capital campaign and long-term planning. One of Foster’s immediate goals is to put together a new strategic plan for Seattle Center. Though it has shorter-term planning documents, Seattle Center hasn’t had a major long-term vision document since the Century 21 Master Plan was adopted in 2008.

“I want to end 2024 with a strategic plan for the future,” Foster said. “It’s not going to just deal with the physical setup. We’re talking about programming, and equity will be at the center of it. And sorting out financial sustainability.”

He also sees this year’s successful return of Bumbershoot, on its 50th anniversary as a featured Seattle Arts Festival, to its artistic roots as emblematic of Seattle Center’s potential. Though the Labor Day music festival brought in 40,000 visitors, Foster says the real success was making it more affordable, and centered on quirky, local arts events in addition to bigger acts.

Foster noted that in a city that’s increasingly facing income inequality and polarization over gaps in wealth and opportunity, Seattle Center offers a unique space where everyone in the city comes together. “We have an opportunity to be a force against that polarization and in helping to bridge that gap.”

Andrew Engelson

Andrew Engelson is an award-winning freelance journalist and editor with over 20 years of experience. Most recently serving as News Director/Deputy Assistant at the South Seattle Emerald, Andrew was also the founder and editor of Cascadia Magazine. His journalism, essays, and writing have appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, The Stranger, Crosscut, Real Change, Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Seattle Times, Washington Trails, and many other publications. He’s passionate about narrative journalism on a range of topics, including the environment, climate change, social justice, arts, culture, and science. He’s the winner of several first place awards from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.