The Seattle Waterfront is set to get a big makeover and the scope of those upgrades got larger thanks to a $45 million gift from a group of local philanthropists led by Melinda French Gates and Mackenzie Scott — two of the richest women on Earth. The infusion of cash has led to a public-private partnership called “Elliott Bay Connections” that is aiming to deliver the waterfront park and trail extension and overhaul in just three years — in time for the 2026 World Cup soccer matches that Seattle is hosting.

The Urbanist sat down with project consultants earlier this month to get a closer look at plans. Former Seattle mayor candidate Colleen Echohawk (whom The Urbanist endorsed in 2021) is leading outreach efforts in her new role as president of Headwater People, an Indigenous-owned and led consulting firm. Ben Franz-Knight of urban development firm Shiels Obletz Johnsen (SOJ) is taking on planning work in partnership with the City of Seattle. Emily Crawford is working on the project with Luminosity, the communications firm tapped in for the project.

Design work (with firm Walker Macy taking the lead) will begin in earnest in early 2024, but their excitement and enthusiasm to improve the waterfront was already palpable as I sat down with the team. Project planners aim to make the waterfront park a true showcase and recreational focal point for the city — in addition to working better as part of the bike and pedestrian network thanks to a new greenway and trail upgrades. The team painted a picture of families coming down to the waterfront park from all over the city to stroll, picnic, and fish off the pier.

The project area stretches from Smith Cove to Pier 62, at which point people walking, rolling, and biking can connect with the new signature feature of the Seattle Waterfront: the Overlook Walk that connects the expanded Seattle Aquarium (both currently under construction) to Pike Place Market. The idea is to integrate the whole waterfront with downtown and make the connection seamless for pedestrians and bicyclists.

The Elliott Bay Trail is also getting a revamp through Interbay in a separate Port of Seattle project, which means trail users will see improvements farther north too. The Alaskan Way Viaduct came down in 2019, unlocking immense potential for the waterfront now free of the hulking elevated double-decker highway and all the noise and pollution it brought, but the last details for pedestrians and bicyclists are still getting sorted out and funded.

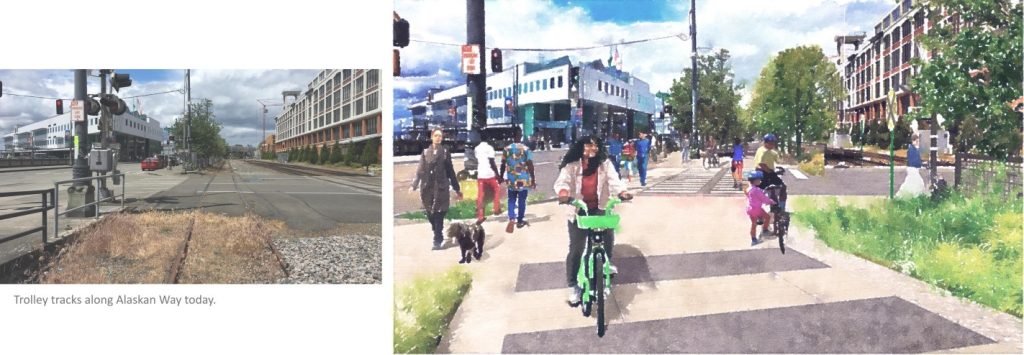

Whether the route is in fact seamless will depend on the connection across Alaskan Way at Broad Street, where the project team said they’d be working closely with the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) and BNSF (whose railyard borders and interacts with the crossing) to provide a good crossing. The Seattle Times first reported on one of the splashier elements of the plan — the conversion of old waterfront streetcar tracks to a multi-use trail. The waterfront streetcar ceased operation in 2005, leaving the abandoned tracks as an obstacle for pedestrians rather than an asset.

“We’ve seen this in response from the community at-large since the announcement, this is a project that people really want to see,” Franz-Knight said. “They know most people love the idea of a greenway coming into this particular section, making it easier to navigate on your bikes, with your strollers and your wheelchairs, and pedestrians, through this area. And so, I’ve already seen a groundswell of support and excitement.”

SDOT is also building a protected bike lane on the waterfront side of Alaskan Way, but that connection will close when cruise ships are loading and unloading, which pushes users to the greenway on the other side of Alaskan Way — or to use the street if they’re brave or impatient enough to do so. The new greenway will stretch three-quarters of a mile from Pier 62 to the edge of the Olympic Sculpture Park.

Cascade Bicycle Club Executive Director Lee Lambert heralded the plan in a City press release and noted that the two facilities serve different types of users, providing a better experience for all.

“Cascade Bicycle Club is excited about this historic investment in making Alaskan Way more bikeable, walkable, and safer for all users,” Lambert said. “Along with the planned bike lanes on the western waterfront side, the green space and additional bike path and better sidewalks on the eastern side of Alaskan Way will support multiple user groups — leaving the western side for transportation and the eastern side for recreation.”

The greenway improvements along Alaskan Way are limited by the fact the Elliott Bay Connections project isn’t touching the street itself and was designed to fit within existing permits to move on a fast timeline. Unfortunately, decisions were made long ago to design the new surface Alaskan Way to have more car lanes than it really needed, which means it’s still unpleasant obstacle for pedestrians and not as green as it could be. However, the new multi-use trail replacing the streetcar tracks will help green the street, the team noted.

“This will be more of a greenway that provides some of that relief, more trees, more plantings, and then wider paths on the east side,” Franz-Knight said.

Staying to the side of the street also sidesteps major construction work on the horizon with the seawall project.

“The other thing that we’re keeping track of is that the City of Seattle will advance the seawall project at some point in the next five to 10 years. And our goal here is to really future proof this side of the street,” he added. “So another reason for us to stay out of the street itself and stay east of the curbs is there’s a whole bunch of utilities, all sorts of things that will have to be relocated and torn out for that next phase of the seawall project.”

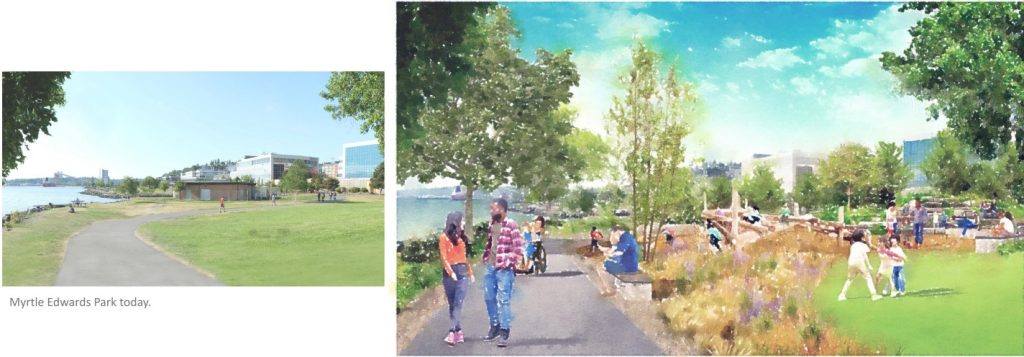

The emphasis for the public parks west of Broad Street will adding native plants to upgrade the monoculture grass and invasive non-native plants that have taken over some sections. Muckleshoot tribal members also advised waterfront project planners about the salmon-friendly plantings being added at the new aquarium, Echohawk said.

“There’ll be a community engagement process, and we’ll be talking with these Indigenous plant experts and hearing what their thoughts are and how we can incorporate those into the space,” Echohawk said. “There are some invasive plants that are down there already. There’s blackberry, there’s ivy, so those will be taken out, and then we’ll replace them with incredibly beautiful plants. What will be exciting is that it’ll be so lush and have more depth — it’s kind of one dimensional right now.”

The project aims to make the two beach coves at Myrtle Edwards Park easier to reach and navigate. Scrambling across uneven rocks and strewn about driftwood is necessary to reach parts of the beach today. Erosion and invasive plants have hit parts of the shoreline hard as well.

The team envisions multi-use trail upgrades throughout, with special attention to the awkward section in Centennial Park where the trail hooks around the public restroom, creating a blind corner with pedestrians. The goal is to straighten out some curving sections and widen the trial where possible to make it more comfortable for people biking to use — and in preparation for a linear park and major bike route that will only get more popular with cyclists and pedestrians alike.

Planners are lavishing special attention on Pier 86 where they will add a food concession stand and restore the public restroom to activate an area that currently feels like more of a pass through. The project will reopen public fishing access at the dock at Pier 86, which has been closed since 2016 due to structural concerns, and plans to introduce artistic projections on the Terminal 86 grain facility — currently drab, plain silos.

Crawford noted fishmongers used to sell fish they caught right out of Elliott Bay the same day at Pike Place Market stands.

“We were talking to Pike Place Fish’s original owner, Johnny, who talked about growing up in the market, and everyone fished down in Elliott Bay,” Crawford said. “They were pulling fish out and then selling it at the market that afternoon.

Salmon runs decreased in recent decades due to pollution and overfishing, but 2023 has seen an uptick in pink salmon, which is restoring hope that the Salish Sea will continue to support plenty of salmon. Bringing back fishing to the pier was important to Echohawk, who noted Muckleshoot anglers still catch fish out of Elliott Bay and eat them today.

“They’re Muckleshoot tribal members, and they’re out there in the boat, and they’re sending pictures of them out there doing what they should… what they’ve been doing there since time immemorial in this space,” she said. “They’ve had a good fishing year, because I’ve gotten lots of pictures.”

Racial equity and environmental justice was a big point of emphasis for the team; they noted hanging at the waterfront park is something a family can do on a budget and that the trail upgrade will make it a lot easier to navigate for families with strollers. Many of the activities are free — from wandering Olympic Sculpture Park to playing at the beach.

The French Gates-led group of philanthropists is not planning to fund park upgrades and tree plantings in South Seattle anytime soon (I asked), but making an accessible welcoming marque park in downtown Seattle will be a welcome improvement — even as low-income people of color tend to live in urban-heat-island neighborhoods most lacking tree canopy and large parks in their immediate midst.

The waterfront project still has a lot of pieces to put together. The bike, pedestrian, and green space elements are on slower timelines than elements focused on cars and freight. The new Elliott Way arterial opened earlier this year, providing a four-lane bypass between Belltown and Colman Dock and SR 99 to the south.

Meanwhile, The Urbanist revealed the Alaskan Way bike facility still under construction ended up being narrower than earlier promises. The two-way protected bike lane and the off-street greenway replacing the streetcar tracks are still to be built between Pier 62 and the sculpture park, as is the Overlook Walk. And the whole thing was latched on to a giant double-barrel highway project that cost more than $4 billion and set the region back on its climate goals.

But, even if some of the pieces were slow to materialize and didn’t fit together perfectly, people are starting to see the end picture and finding it’s something to get excited about. Seattle could soon finally have a waterfront welcome mat befitting an Emerald City with a mariner reputation.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.