The County’s cringeworthy move suggests more attention is needed on boosting service and electric trolleys.

King County Metro will roll out new light yellow paint jobs to differentiate its new battery-electric buses from the rest of its fleet of older hybrid diesel buses and electric trolleys. The yellow branding wraps will begin appearing on new battery-electric buses that enter service starting in 2025.

Intended to celebrate the agency’s 50th anniversary, the announcement ended up earning criticism from transit advocates and came across as clumsily timed and out of touch given the serious problems that the agency faces. Despite the battery-electric bus branding scheme dubbed “New Energy,” the new buses are less reliable and have a shorter range than the previous generation of buses due to the limitations of battery technology. Nonetheless, Metro is betting on them — even though keeping buses in service is at a premium given shrinking service and reliability issues.

Constantine attracts the ire of transit riders again

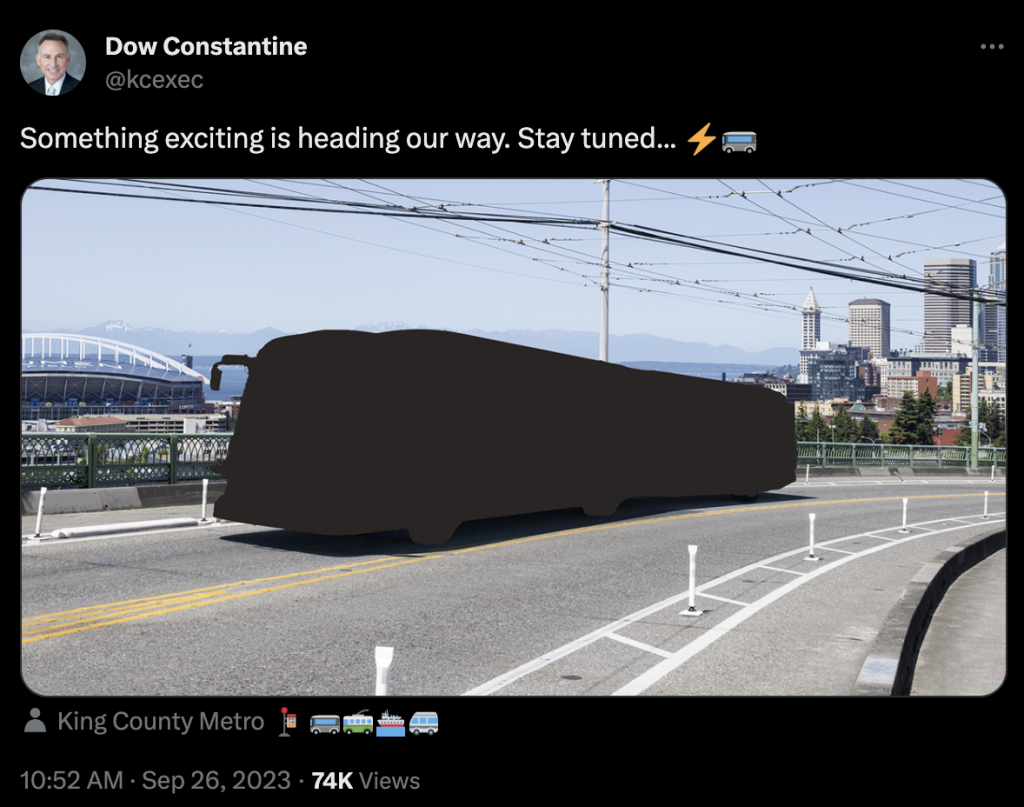

On Tuesday, King County Executive Dow Constantine shared a photo on social media of a silhouetted bus below electric trolleybus wires ordinarily used by Route 36, a workhorse of the system. The silhouetted bus, however, clearly was not an electric trolleybus — the greenest type of bus in Metro’s portfolio and accounting for about 12% of its fleet — since there was no pantograph to connect the trolley to the overhead wire.

On social media, Constantine was pilloried by transit riders pointing out the odd background choice for the silhouetted bus and the fact that Metro is failing riders on service quality and frequency. Just this month, the agency took a dramatic cut in transit service to match available staffing and equipment levels. That meant cutting back on both all-day high-ridership service as well as peak-hour commuter routes.

Hampered by a bus operator shortage, Metro is still well below pre-pandemic service levels at around 90% of service, factoring in missed trips. Relatedly, ridership is around 60% of pre-pandemic levels.

In 2020, King County Council was considering running a countywide transit measure (similar to Seattle’s transit measure) that could have boosted bus service, but it shelved the measure amid the pandemic. Even after officials declared the pandemic vanquished, Constantine has not pushed for bringing back the county transit measure and councilmembers have let it stay in the dustbin despite interest from the original sponsor Claudia Balducci and leading candidates for open county council seats (see The Urbanist’s endorsements for who those are).

The great reveal on Wednesday similarly did not go over well when the silhouette was removed to show a rendered battery-electric bus in place of a trolleybus. Transit riders appeared even more riled than before. Constantine was undeterred and flooded his social media timeline to highlight new bus branding and promote Metro’s risky and condensed zero-emissions fleet conversion strategy.

Unfortunately, the county executive being out of touch is increasingly a theme. Constantine has been heavily focused on what appears to be aesthetics and legacy-building moves. He’s thrown his support behind an unrealistic vanity redevelopment of county properties in downtown Seattle. Flashy images of structurally unbuildable highrises were plastered about his press releases in the announcement this spring. And despite broad opposition to his plan to kill the voter-approved Link light rail stations in Chinatown and Midtown, he hasn’t made any effort to make them preferred and ensure that they move forward, rather sticking by his “Jail Station” location on the county campus.

Meanwhile, Constantine has moved much of the county’s staffing footprint out of downtown Seattle, an action that is less convenient for users of County services and will contribute to disinvestment and destabilization of local communities.

New Energy coming soon

The new branding, called “New Energy,” will only appear on battery-electric buses in two forms as vehicles come off the factory line. A modern yellow and seafoam green blend will replace the blue/gold and green/gold livery for non-RapidRide buses. A separate modern blend of red and purple will replace the red/gold on RapidRide buses. Metro plans to emblazon the word “ELECTRIC” on the seafoam green and purple accents. As for electric trolleybuses, they will stick with their current purple/gold branding.

Teague, a design consultancy tapped by the county last year, carried out the simple rebrand at a cost of about $130,000. Procurement documents show that the county directed Teague to provide at least one or more designs for Metro’s regular fleet (i.e., non-RapidRide buses) and a design for the RapidRide fleet, provided that some key branding elements be retained. While the county is not poised to replace the relatively new electric trolleybuses for several more years, the lack of attention on the electric trolleybuses is conspicuous.

Nevertheless, the new branding will appear on a lot of buses in the years ahead. Between now and 2035, the county is set to replace about 1,350 buses. The bulk of those are hybrid diesel-electric buses, but 174 are electric trolleybuses.

Battery-electric buses really aren’t all they’re cracked up to be

There are very real tradeoffs with battery-electric buses. The biggest is their reliability and the distance that they can travel. Battery-electric buses are still in a nascent stage of development and as a consequence they aren’t nearly as reliable as their hybrid diesel-electric counterparts. The distance they get on a single charge also isn’t that great and charge times can be significant. Manufacturers are trying to address this with more fast-charging equipment, particularly in the field with induction chargers, but that still doesn’t bring vehicles back anywhere close to a full charge when passively charging at a layover or short dwell spot.

As an example, the best 40-foot battery-electric New Flyer Xcelsior variant only gets about half the range of its hybrid diesel-electric counterpart. Lower performing battery-electric Xcelsior variants can only reach a third of the range. And it bears mentioning that weather conditions can wildly affect battery performance with cold weather being a serious culprit in zapping range.

The reliability and distance issue therefore translates into a related problem. A much larger number of battery-electric buses is required to operate the same level of service that hybrid diesel-electric buses provide. That means more storage space, which comes at a serious premium, is also required if existing service levels are even just to be maintained and this is to say nothing of the fleet displacement impacts that converting parts of bus bases to battery-electric creates.

Another issue is that unit costs for battery-electric buses are usually a third or more higher than their hybrid diesel-electric counterparts — not accounting for pricey charging equipment. New grant opportunities under the Climate Commitment Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law can partially close that gap, but it doesn’t change the fact that costs are so much higher and that hybrid diesel-electric buses still qualify for other state and federal grants.

Metro’s timing of all-out battery-electric bus acquisition could be complicated by a changing bus manufacturing environment. The number of Buy America-approved manufacturers actually offering battery-electric buses is going down, not up — thereby reducing innovation, production capacity, and competition.

The main benefit of battery-electric buses is that they’re quieter, require less maintenance, and provide localized elimination of tailpipe emissions. However, the amount of climate emissions avoided by them is fairly negligible as public transportation buses only make up a very small fraction of area emissions. Regular vehicles make up most of Puget Sound’s emissions and go unaddressed by transit fleet choices.

Burning diesel fuel does create considerable particulate pollution, but again freight vehicles account for far more of this than hybrid diesel-electric buses. Plans to tackle freight pollution have been timid and have not gotten much attention from local officials.

So with that context, it really begs the question of what a transit agency is and isn’t getting by being an earlier adopter of a fully zero-emissions fleet. Bragging rights are certainly a bonus. Bona fide emissions reduction from operations to report on spreadsheets is another. But what a transit agency is leaving on the table, absent a growing fleet and source of funding, is more service and transit riders who leave their cars behind eliminating more significant greenhouse gas emissions and toxic tire particulate pollution.

In 2035, riders could still be squawking about infrequent local bus service and a shrinking bus network all in service of a 100% zero-emissions fleet.

Under Constantine’s watch, trolleybuses have been neglected

Despite the county’s bluster over pursuing a zero-emissions fleet transition, a big area of neglect has been the electric trolleybus network. Expansions like Route 48 via 23rd Avenue and a small extension down NE 45th Street to Laurelhurst for Route 44 have been proposed for years with little action. Indeed, installing new traction power stations and poles with wires is not without some upfront costs, but expansion costs actually aren’t all that great on a per-mile basis. The county could qualify for special and very lucrative grants since electric trolleybuses and their infrastructure are considered fixed guideway transit under federal law.

Given the volume of ridership, frequency, and length of many routes, there are a bunch of obvious corridors like Routes 5, 8, 40, and C, D, E, G, and H Lines that are worthy of electric trolleybus network expansion in Seattle. That might not be a prudent choice in the more sprawling suburban areas of the county, but it is a financially and environmentally sound choice in the city that the county continues to overlook without justification.

The county is in desperate need of political leadership around transit, but this week Constantine reinforced that it won’t be coming from him anytime soon. Instead, he’s sticking with superficial talking points and meaningless feel good gestures. But hey, enjoy the shiny new bus renderings.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.