What comes next when a “transformational” levy didn’t transform Seattle streets?

On a Monday morning in late August, Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) Director Greg Spotts started his workweek with a walking tour in West Seattle. That’s a usual day for Spotts, who has made a point of regularly meeting with staff in the field since officially starting work in the role last September. But what was unusual is that the tour wasn’t in the vicinity of a planned project or a neighborhood problem spot in need of a fix, but in an area where SDOT had already wrapped work on a street repaving that added a protected bike lane and peak-hour transit lane more than three years earlier.

The project, along Avalon Way SW, had been completed just a few months into the Covid pandemic during the summer of 2020, a time when a new bike lane and a freshly paved street was slightly overshadowed by other events happening, locally and nationally. But the visit this year, a chance to circle back and look at the improvements that the city made along with its maintenance work, signaled something much bigger: the days of Seattle’s current Move Seattle transportation levy, which has funded many projects including this one on Avalon Way, is coming to a close.

With nine years of projects, multiple mayoral administrations and a fairly steady pace of new leadership at SDOT since the passage of the levy in 2015, getting a sense of what the levy actually did will be central to figuring out where the department is heading next, as Mayor Bruce Harrell’s administration starts to put together whatever will succeed it.

“The most equitable transportation package Seattle has ever seen”

The Move Seattle Levy, introduced by Mayor Ed Murray in spring of 2015 and revised by mid-summer into the form voters ultimately approved, represented a big step up in transportation funding for SDOT compared to the previous Bridging the Gap levy. As its name implied, Bridging the Gap had been an attempt to use a property tax levy to fill in the city’s growing maintenance backlog of projects.

Move Seattle was a step above that. With a plan to collect a total of $930 million over nine years compared to the $365 million from Bridging the Gap, the new levy was framed as getting the city out ahead of its problems by upgrading bus lines, adding bike lanes, and improving connections to light rail, in addition to making the significant investment in road maintenance that would keep the backlog from continuing to compound. The levy constitutes a staggering 30% of SDOT’s overall budget.

Dubbed by Councilmember Mike O’Brien as “the most equitable transportation package Seattle has ever seen,” the proposal also took aim at some of the places in the city where investments hadn’t traditionally been made, and used the city’s new “racial equity toolkit” to determine where those investments should go. Safety corridor projects on MLK Jr Way S and Rainier Avenue S were promised, the conversion of the Route 7 into a RapidRide line, and funding to help Sound Transit add another light rail station in the Rainier Valley at Graham Street.

The levy also became closely associated with the city’s new goal of redoubling efforts to get to zero fatalities and serious injuries from traffic by the year 2030. The new Vision Zero program, which was rolled out just a few weeks before the Move Seattle package and vision, jumped on a trend of U.S. cities adopting safe streets language from Europe and added urgency to ensure that the investments in the coming levy centered safety improvements, an aspect that became highlighted in the ballot measure’s ad campaign.

While Bridging the Gap had directly funded King County Metro service, Seattle had just passed another ballot measure in 2014 to do exactly that, setting Move Seattle up to fund upgrades to streets to keep buses moving. While Murray had originally proposed just three full transit corridor upgrades when rolling out the initial proposal for the levy, by the time that went to voters that had been upgraded to seven. The proposal set aside $104 million, which was to be matched with federal dollars, with the hopes of rolling other needed improvements, like bike lanes, in with those projects as well.

When elected in 2013, Murray had not been the safe streets candidate. Mike McGinn had earned that distinction after winning as an outsider candidate in a shocking upset in 2009, buoyed by advocates for safe streets and climate action. Murray narrowly edged McGinn out in 2013, but, once in office, he set about winning over McGinn’s multimodal supporters by quickly implementing the safety projects McGinn had queued up, committing to a Vision Zero pledge, and backing it up by lowering speed limits on non-arterial streets.

Falling short of expectations

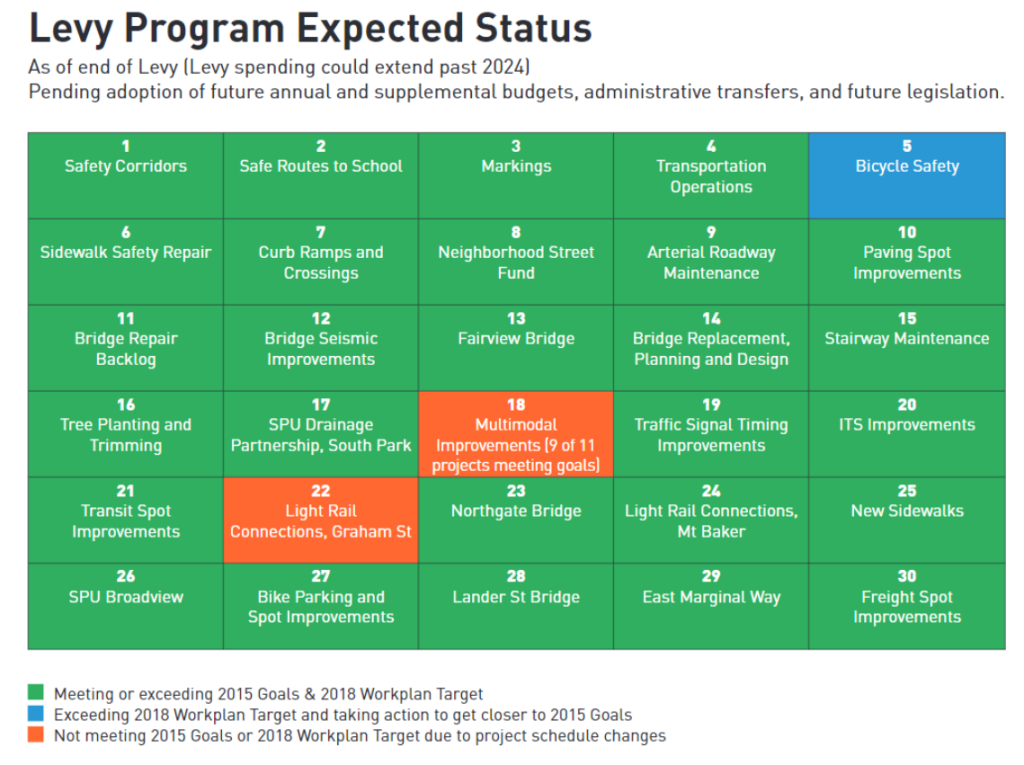

Earlier this year, the Seattle City Council’s transportation committee got a status update for the entire levy, with about 18 months left in its lifespan. Center stage in that presentation is a chart showing green and orange boxes for each individual levy program: green meant the program achieved what voters approved, orange or blue meant it fell short.

The chart was a sea of green; just three programs, 10% of the total, were falling short and unlikely to meet their original target by the end of 2024, according to SDOT. But with so many individual promises and ways of looking at the targets, that chart doesn’t show the entire picture, and it also gets to the heart of why so many people have differing perspectives on how Move Seattle performed.

One example: the 16 promised seismic upgrades to the city’s bridges are on track. But only because two of the biggest-ticket expenditures planned for that program, upgrades to the Fremont and Ballard Bridges, were swapped out for other, smaller bridges that were more feasible given the program budget. But those larger projects still loom on the horizon.

Similarly, SDOT set a goal of completing 12 to 15 “safety corridors” across the city, and the chart shows the department set to clear that goal with room to spare. But MLK Jr Way S, Airport Way S, or Aurora Avenue N, all called out by name in 2015, didn’t see any significant safety upgrades. If you were voting for the levy in the hopes of seeing your dangerous and busy street nearby tamed and turned more walkable, a green box could be seen less as consolation and more as an insult.

The event that likely did the most to shape broader public perceptions of the how Move Seattle actually performed was the 2018 “reset” conducted during Mayor Jenny Durkan’s first year in office. At the time, SDOT sought to grapple with a number of overlapping issues. Costs for projects were coming in much higher than had been projected on paper, and federal grants, which were a big part of the planned levy portfolio, were proving to be incredibly hard to secure under the Trump administration.

The reset was also an exercise in lowering expectations for a Durkan administration that didn’t want to be held to the dreamier visions of the preceding Murray and McGinn era and didn’t have the resources (without raising additional resources locally) to achieve them even if it did. Nonetheless, it compounded a perception during the early years of Move Seattle that things were being scaled back.

“We had a really strong mandate to build out significant walking, biking, and transit improvements. And it’s still continuing to be a slog throughout the last nine years to get those projects implemented,” Gordon Padelford, the executive director of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, told The Urbanist. “So there’s definitely disappointment that SDOT wasn’t able to move faster, and more boldly to implement some of those projects. There are a bunch of factors that lead into that: external, internal, political. But I think the sense was just a lot of optimism coming out of the passage of that levy because it was a fairly bold levy that had a really strong multimodal and safety component.”

Looking back on ambitious goals

At a Capitol Hill cafe this summer, looking out on the still under-construction RapidRide G project, I met with Francisca Stefan, SDOT’s Deputy Director in charge of capital project delivery, and Serena Lehman, project and portfolio team manager for Move Seattle, to discuss how the expiring levy is viewed inside the department. What became clear over the course of our conversation is the degree to which Move Seattle is seen as providing a significant benefit to the department that sets SDOT up for more positive steps forward in the future.

“There’s an interesting dynamic about the levy: If you were to think about, what if we hadn’t had it?” Stefan told me. “I think if we hadn’t had the commitments, numeric or otherwise, you know, would we have gotten as much as we have gotten as a community? And I would argue, no, even if there’s a sense of disappointment. The sheer striving for a target delivers a lot more than an amorphous attention.”

The 2018 “reset” of levy goals received a great deal of attention, but another recalibration in 2021 received far less notice. That year, SDOT worked with the levy’s oversight committee to update the portfolio of projects funded by the levy and look at reinvesting some additional funding that included excess funds from the Lander Street Overpass and the John Lewis Pedestrian Bridge. The agency sought to prioritize projects that were most behind their original 2015 goals.

Due to the levy’s commitment to build 110 miles of new bike infrastructure, funds were moved over onto projects like the Georgetown to Downtown bike route. “[The] bike [program] is one of those that was falling short,” Lehman said. “And without that goal, that very public goal? I don’t know…I don’t have a sense one way or another, if there would have been enough will to move that funding over there.”

Stefan painted a picture of a transportation department, at least on the project development side, that was able to hit its stride with the funding provided by Move Seattle… just not on the timeline that the city might have expected.

“I understand that there was a certain lag time and like, okay, Bridging the Gap was a third of the size, right,” Stefan said. “And so to effectively manage, track, implement that kind of funding, it did take a different structure. But I think we have a pretty good structure in place now,” Stefan said, citing new back-of-house systems to track projects and staff in place to conduct audits. “So while it may have taken some time, it wasn’t put in place as temporary.”

Building the bike network

The high profile goal of adding more than 100 miles to the city’s bike network was a big selling point for Move Seattle, and has become a focal point for advocates who say the levy didn’t live up to its promises. The original funding allocated to the bike program in the levy definitely fell considerably short of what would ultimately be needed, and it took an extraordinary amount of additional pushing. For example, advocates lobbied and convinced the Seattle City Council and Mayor Durkan to use funds from the sale of the City-owned Mercer Megablock, and they won bike and pedestrian investments from public benefits packages from megaprojects like the Washington State Convention Center expansion and Climate Pledge Arena overhaul.

Vicky Clarke, policy director for Cascade Bicycle Club, was less interested in what the final number of miles will end up being, and more eager to zoom out to the big picture of what the investments started by Move Seattle were able to do.

“When I think about where the bike network was in the beginning of 2016, and where it is now, and the things that I hear from people… we have a Downtown Seattle that has a basic bike network,” Clarke said. “The fact that I could get on a bike in Pioneer Square to go to the neighborhoods: Magnolia, Fremont, affluent North Seattle neighborhoods — almost to Northeast Seattle, except for Eastlake… you couldn’t do that before.”

“There’s clearly so much more to do, right,” Clarke said. “This was clearly a levy that was, project-wise, really heavy downtown, heavy North Seattle, a lot lacking in West Seattle, in Southeast Seattle, [where] biking down there is like going back in time a decade,” Clarke said. “And so there’s more to do, but I don’t want to discount what has been done.”

On the other hand, moving projects forward that were intended to correct some of those imbalances of the past decades that have centered investments in areas like downtown and North Seattle was a central promise of the levy.

What happened to Accessible Mount Baker?

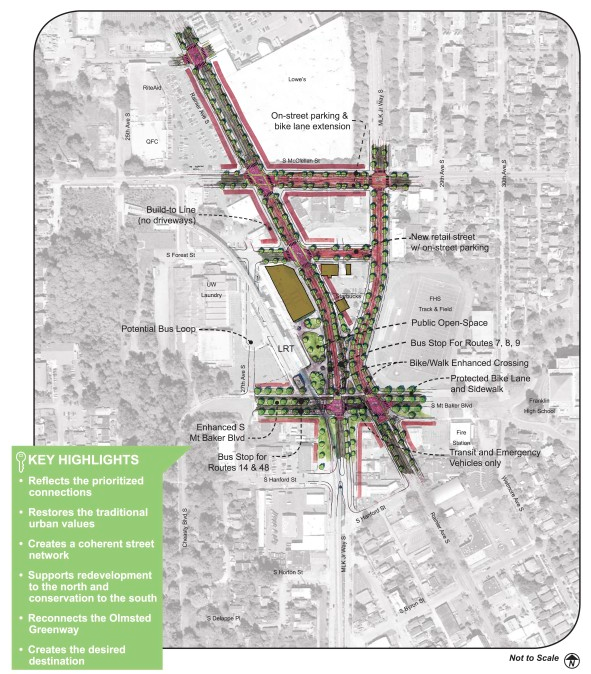

Standing among the cadre of elected officials in 2015 touting the potential for Move Seattle was Rebecca Saldaña, future State Senator, at the time the executive director of Puget Sound Sage. Taking the microphone, Saldaña touted two projects that would help drive equitable outcomes and allow residents of the Rainier Valley to access transit: Sound Transit’s planned infill light rail station at Graham Street, which the City of Seattle would be contributing $10 million, and a bold idea to transform the streets around Mount Baker’s light rail station: “Accessible Mount Baker.”

“What we’re doing is trying to bridge the gap, to make sure that our policies and our investments as a city are about making sure that we are building an inclusive, affordable, city for all,” Saldaña said at that press conference. “The investments at Mount Baker and the investments to support Graham Street station, are critical. We have multiple schools, mosques, the Filipino Community of Seattle, that are all right there, not being able to access this huge investment that we’ve made in light rail.”

The Graham Street infill station between Columbia City and Othello fell victim to cost pressures at Sound Transit that forced the agency to prioritize other projects and push out the timeline for Graham Street to 2031; the City of Seattle says it remains committed to providing its share of funding for that station when the time comes. But from today’s perspective, few projects represent the difference between the lofty goals of Move Seattle and what actually came to pass more than Accessible Mount Baker does.

Move Seattle was intended to get the ball rolling and create momentum for the bold vision to tame the daunting intersection that is Rainier Avenue S and MLK Jr Way S by carving out street space for walking, biking, public space, and transit. But what appears to have happened instead was the project falling through the cracks as one mayoral administration turned to another and the city’s elected leaders lost sight of that vision.

The levy earmarked $6 million specifically for “early portions” of Accessible Mount Baker — improvements that still haven’t started construction 15 months from the expiration of the levy. The fact that those dollars were specifically earmarked can be traced back to an amendment by the city councilmember from District 2 at the time: Bruce Harrell.

Harrell said that his amendment, introduced as the city council prepped Move Seattle to head to the ballot, was intended to do “what the director and the executive will do anyway” in moving Accessible Mount Baker forward. But while construction is set to start on some modest improvements at MLK and Rainier, including a long-needed crosswalk across the final leg of the intersection, the City is no further along today in advancing the new vision around Mount Baker that prioritizes people outside cars at one of the city’s most dangerous intersections.

With so much faith put in federal grants in 2015 to be able to provide matching funds for Move Seattle projects, by the time those dollars actually started flowing, the city wasn’t ready to grab them. In 2022, SDOT passed on applying for construction funds as part of the U.S. Department of Transportation’s RAISE grant program, with an internal memo noting that no projects were at the stage where they were ready to go out for grants, even just for planning. One of the projects considered? Accessible Mount Baker.

Lessons for the next levy

Behind closed doors, the next transportation levy is being shaped right now, against the backdrop of a stretched-thin city general fund that will almost certainly be able to provide less support for transportation and a construction climate in the city that is providing fewer real-estate taxes for capital projects. But this levy won’t need to respond just to the immediate future, but the next decade of the city’s growth, as Move Seattle did with mixed results.

On SDOT’s side, leadership is clearly interested in learning from the mistakes of this levy when it comes to measuring performance. “Looking forward, whatever we craft, whatever our next package is … we want there to be a consistent North Star that we’re holding ourselves to, because it’s been very confusing for the public,” Lehman told me.

“I think it has by its very nature had to be a dynamic process. But we’re also trying to manage the opportunistic dynamism of it with a predictable transparency piece of the puzzle,” Stefan said.

But given the widely held perception that Move Seattle set its sights too high, the question of whether 2024’s levy should aim lower is top of mind. Advocates looking for the city to live up to the transformative vision set out in Move Seattle don’t want to see that happen.

“No, I think it needs to be more ambitious if anything, but we need to have a realistic plan to get there,” Padelford said. “I think Bridging the Gap was progressive for its time, and moved us incrementally towards a vision of a more multimodal city. I think the Move Seattle levy took a bigger step forward. But fundamentally, I still think they were still sort of incremental approaches to changing our streets. And I think folks are now ready and hungry for transformational change. And we need a transportation levy that pushes us boldly forward, and not just for taking incremental steps.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.