Under the pilot program, up to 35 qualifying projects could get a density boost for adding affordable homes in historically marginalized communities.

Workforce housing is in short supply in Seattle. Councilmember Tammy Morales (District 2 – Southeast Seattle) wants to change that. A new initiative she’s backing would introduce an equitable development pilot program into the city’s land use code. Focused on community-based projects, the initiative would direct new workforce housing and equitable development uses in historically disadvantaged portions of the city and areas of the city where racism was inherently incorporated into property covenants.

Dubbed the “Connected Community Development Partnership Bonus Pilot Program,” Morales’ legislation would offer non-profit organizations and public development authorities a new pathway to achieve substantial density bonuses and establish community-oriented services. Eligible projects would be able to use those new density bonuses and zoning flexibility in the city’s myriad Neighborhood Residential, Multifamily, and Commercial zones.

At a city council committee meeting on Friday, Morales said that the proposed land use code changes came out of a stakeholder process that’s been ongoing since 2022 with about 35 community organizations. The goal of the changes, she said, is to “shift the city toward one where everybody can live in their chosen neighborhood with access to services and commerce that meet their needs, all ideally within a 15-minute walk or roll of their home.”

There are a lot of moving parts to Morales’ legislation.

Firstly, the legislation being a pilot program means that it would be limited. The number of eligible project applications would be capped at 35 with the pilot program running to 2029. The pilot program, however, could end earlier if 35 bona fide applications are received sooner than the sunset date.

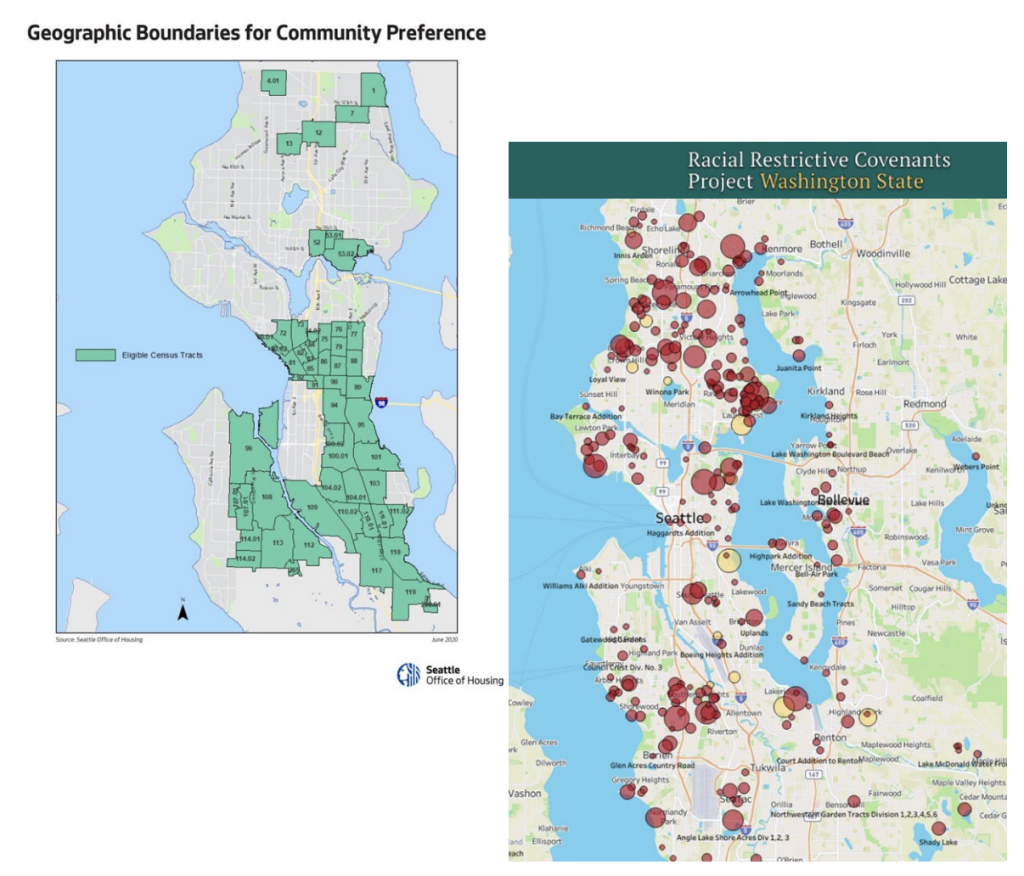

Secondly, the legislation stipulates several circumstantial and locational limitations. Eligible projects would need to be located on property owned or controlled by a community development organization and either located in a Community Preference Policy area or area with documented racially restrictive covenants. In Commercial zones, at least three-quarters of the project floor area would need to be residential in nature. And eligible projects would generally be prohibited in designated historic districts, though not in areas that have documented racially restrictive covenants.

Thirdly, the legislation would exempt eligible projects from the city’s design review and the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) programs — negating the need for a lot of public process and requirement to either pay a fee or provide on-site affordable housing. Eligible projects, however, would still need to meet certain affordability requirements that on balance may be the same as or greater than MHA, but by targeting potentially higher income levels and income-restricting many more units. MHA requirements restrict rents below 60% area median income (AMI) for participating rental units, which typically must equal between 5% and 11% of a building’s total units depending on the intensity of the upzone.

The legislation calls for at least 30% of units in projects to be affordable for 75 years. That’s defined differently depending upon tenancy type, with rental units restricted to households at or below 80% of AMI and ownership units restricted to households up to 100% AMI. Rent and sales prices of such units would also then be made affordable for an ongoing basis, generally no more than 30% of a household’s monthly income.

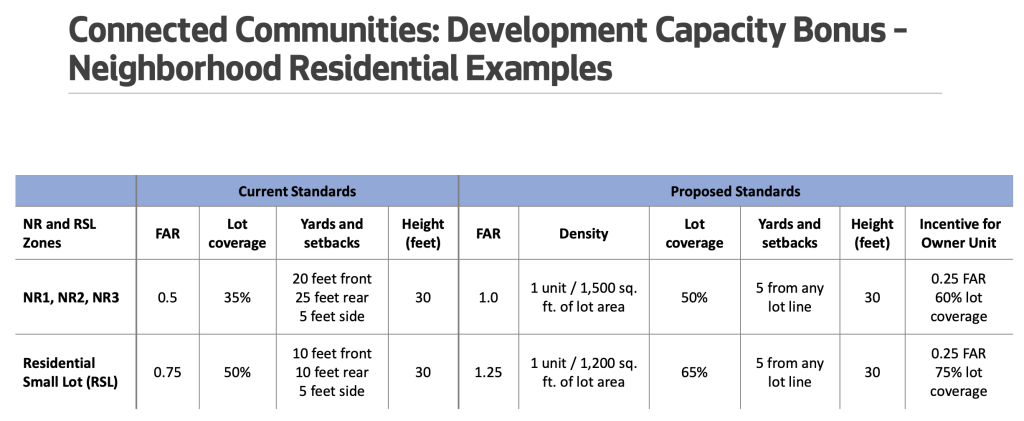

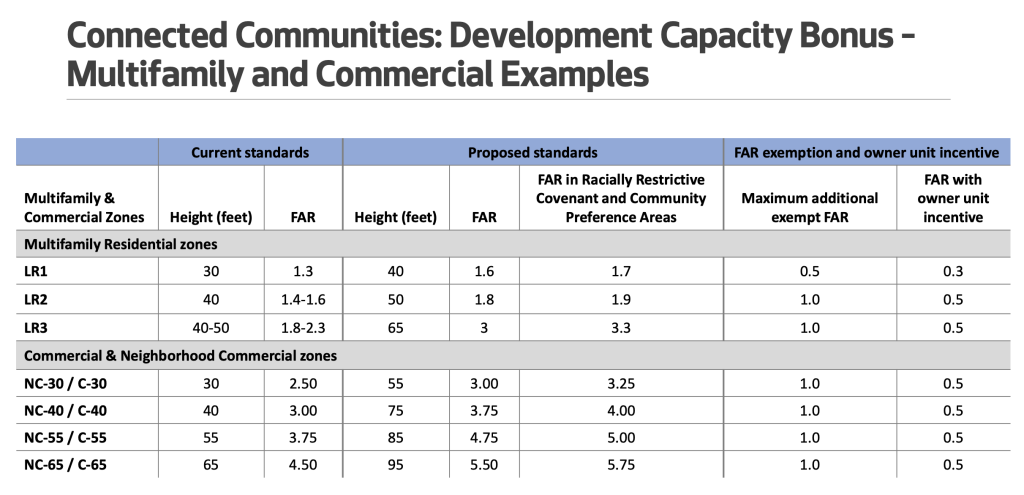

Finally, the legislation has much to say about how alternative development standards could apply in the city’s Neighborhood Residential, Multifamily, and Commercial zones. A presentation put together for Friday’s meeting provided fairly comprehensive tables detailing current zoning standards and how the alternative development standards would offer meaningful bonuses over the status quo.

For Neighborhood Residential (NR) 1, 2, and 3 zones, the alternative development standards would significantly reduce setbacks, raise lot coverage allowances by 15% to 25%, double or more the allowed floor area ratio, and generally allow two or more additional principal dwelling units on most lots. Similarly, Residential Small Lot (RSL) zones would see consequential jumps in development capacity with up to an 80% increase in units per lot, 15% to 25% increase in lot coverage, 0.50 to 0.75 increase in floor area ratio, and a meaningful reduction in setbacks.

In the NR zones, a spectrum of new housing types would be allowed under the alternative development standards, including cottage housing, rowhouses, townhouses, and apartments. Those housing types are already allowed in RSL zones, but both NR and RSL zones would see the additional allowance of equitable development uses — things like gathering, arts, and culture spaces, job training spaces, and light commercial activities.

Eligible projects in the NR and RSL zones, however, would need to be on sites that are at least 10,000 square feet in size. Perhaps at that scale, some projects could pan out but assembling sites from abutting single-family lots could be challenging.

In the Multifamily and Commercial zones, the increases in development capacity under the alternative development standards are probably more significant and enticing to potential project applicants. The legislation details substantial increases in height limits across the many Multifamily and Commercial zoning types as well as boosts in floor area ratio increments and exemptions. Like NR and RSL zones, equitable development uses would be permitted even in the Multifamily zones, and naturally in Commercial zones. A small sliver of Multifamily zones have density limits on units in certain cases, but the alternative development standards would fully waive those for eligible projects.

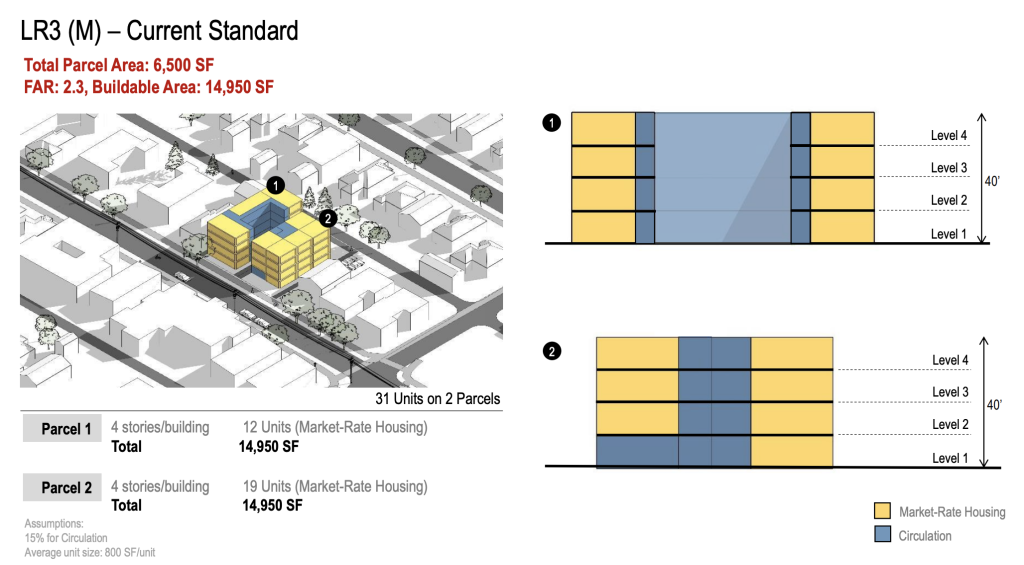

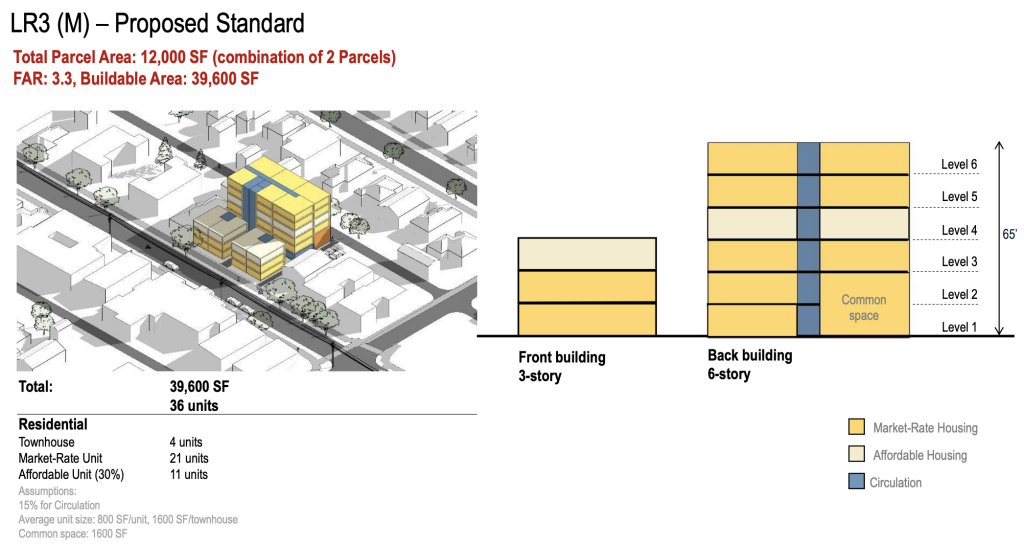

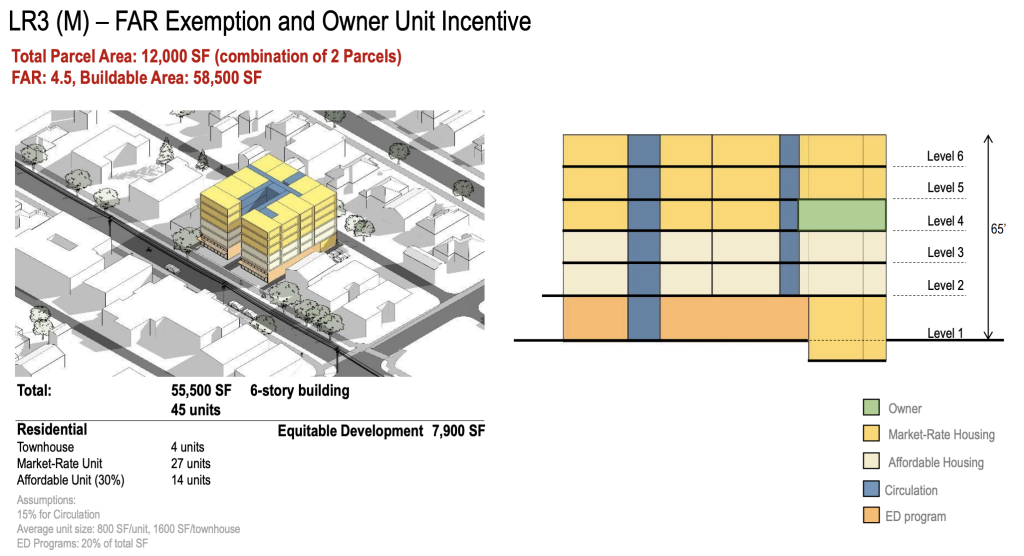

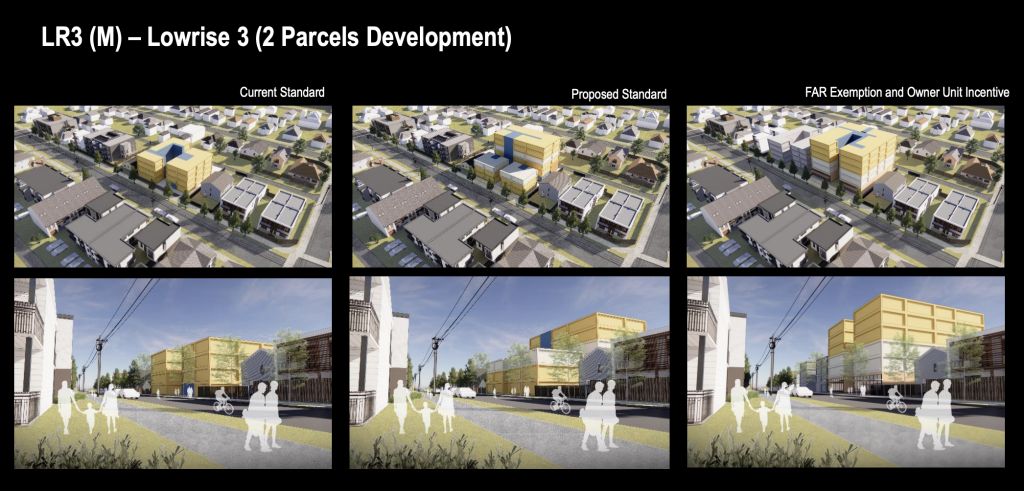

City staff have already done a lot of legwork in modeling the potential impact of the legislation. Using a Lowrise 3 zone scenario, the city council’s design consultant, Schemata Workshop, produced theoretical projects on a two-lot site using rough height/bulk/scale massings. The modeled scenario considered projects trying to maximize zoning regulations under current regulations, the proposed standard alternative development standards, and proposed alternative development standards with all possible bonuses.

The City’s modeling found varied outcomes depending on the type of project pursued. Using the basic proposed development standards, an example LR3 site could go from maxing out at two, four-story apartments with 31 market-rate units under today’s regulations to supporting 36 units with four townhouse units (across two buildings). Of those 36 units, at least 11 would be income-restricted. But if the developer maxed out proposed development standards with all bonuses, a project could deliver 45 units and equitable development programming in a single 6-story building. Of those 45 units, at least 14 would be income-restricted.

At Friday’s meeting, fellow Councilmembers Sara Nelson (Position 9 – Citywide) and Dan Strauss (District 6 – Northwest Seattle) didn’t exactly tip their positions on the proposal, but Strauss did explicitly thank Morales for continuing work on the effort. The legislation will eventually make its way to the land use committee that Strauss chairs.

Before the legislation can move forward, environmental review under the State Environmental Policy Act must be completed. That process always presents a risk of delay due to potential appeals, but the tight nature of the pilot program may ward off that specter. If all goes according to plan, Morales’ legislation could get a formal consideration in committee sometime in December with final adoption in the new year, but process and the budget season abound.

Wrapping up her discussion on Friday, Morales said this effort is ultimately about creating the kinds of communities people want, the kind that “provides for a mix of incomes in any given building and makes sure that we are setting an intention that the ground floor of these buildings provides a service to neighbors.”

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.