A Strauss resolution would give the freight board more oversight and chance to block changes to truck streets.

An under-the-radar resolution moving through the Seattle City Council could be about to open the door to additional scrutiny of high-impact safety and mobility projects planned for some of the city’s most dangerous streets. Originally intended to encourage city departments to work with industrial businesses and organizations to improve operation of Seattle’s freight networks, last-minute changes raised eyebrows among safe streets advocacy by appearing to prioritize vehicle movement over safety.

The resolution, which has been shepherded by Land Use Committee Chair Dan Strauss, directs the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) to analyze its existing transportation plans in order to “prioritize freight movement on streets classified as major truck streets” and includes language that would empower the city’s volunteer board that advises on freight mobility issues to more forcefully push back on any changes intended to reduce fatal or serious injury crashes.

“When a transportation project may result in the reduction in the number or width of lanes along a major truck street, the Council requests that SDOT offers a briefing to the Seattle Freight Advisory Board and the Seattle City Council’s Transportation and Seattle Public Utilities Committee, or successor committee with purview over transportation issues, with a goal of demonstrating that adjacent land uses and through traffic will not be compromised,” the new language in the resolution reads.

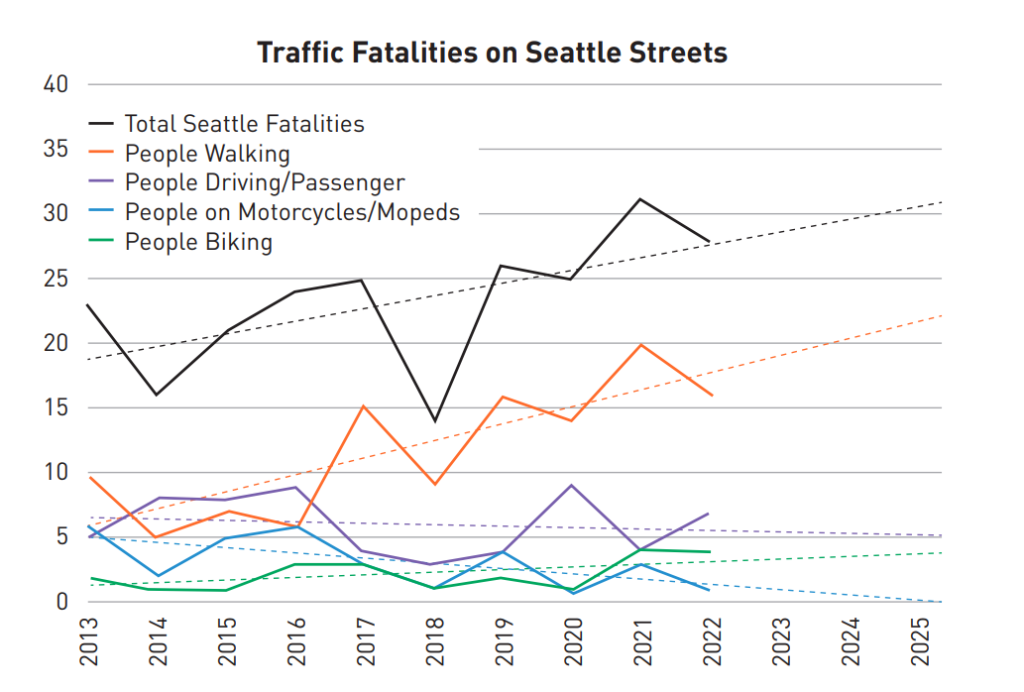

That wording seems to be in conflict with some of the City’s broader goals around reducing serious crashes and shifting city residents out of their single-occupancy vehicles. It could throw up obstacles to completing planned safety projects and making progress toward the City’s Vision Zero pledge to eliminate traffic deaths by 2030. That Vision Zero pledge is already is well off-course at the current pace of building safety infrastructure, and adding more hurdles would not help.

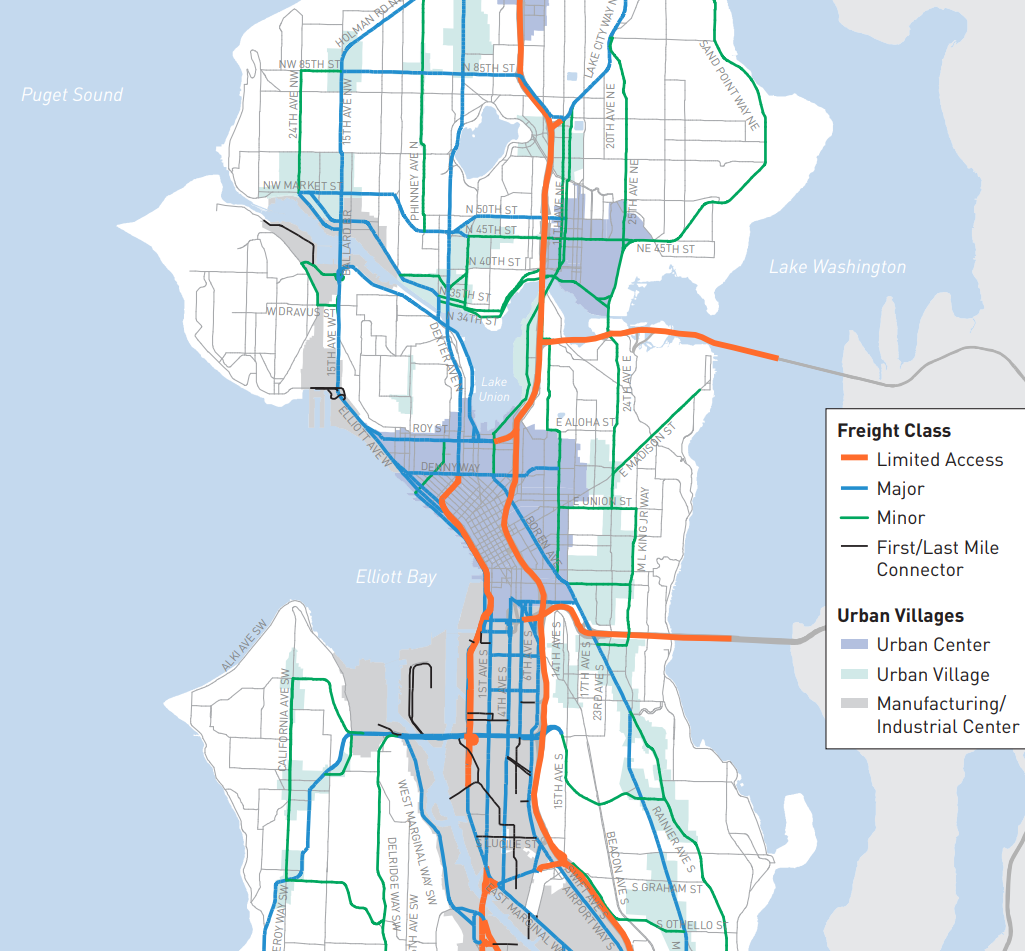

Some of the most impactful street improvement projects across the city, from a planned bike lane on Airport Way S in Georgetown, to a new plan to study rerouting the Burke-Gilman Trail’s missing link on Leary Way NW in Ballard, to a complete safety overhaul of Aurora Avenue N, all impact “major truck streets,” and establishing a bar of no impact whatsoever to vehicle throughput on those streets could create a considerable new hurdle.

The resolution was originally introduced in July, to be paired with a long-awaited overhaul of the city’s industrial and maritime land use regulations. The changes tweak zoning in the city’s industrial lands to potentially allow 3,000 new units of housing that wouldn’t have been permitted, but freight and industrial interests pushed back on the idea of allowing more housing around the sports stadiums in SoDo, a collision hotspot with more serious and fatal traffic crashes than any other part of the city. The goal of maintaining freight vehicle capacity in that area of the city played a major role in their advocacy on the topic.

Originally, the language around maintaining “through traffic” was not included in the resolution. Instead it had only directed the city to “improve the movement of workers and goods by making transit and freight networks more efficient” — work the city is already doing by exploring new programs like dedicated freight lanes and freight spot improvements around the city. But early this week, the city council’s land use committee reviewed a new version of the resolution that included the stronger language.

Major truck streets aren’t just located in the city’s Manufacturing and Industrial Centers (MICs) but extend throughout the entire city, and include important pedestrian-oriented transit corridors like NW Market Street in Ballard, Rainier Avenue in Mount Baker, and Westlake Avenue in South Lake Union. The way these streets operate now, there is a fundamental tension that exists between providing incredible amounts of vehicle capacity to get freight traffic in and out, and being local neighborhood streets.

The resolution also directs the city to “support Vision Zero projects with unique industrial-area applications to reduce traffic deaths and injuries,” but many of the Vision Zero projects that have been proposed in recent years have received considerable pushback from businesses concerned about freight.

For example, plans to implement traffic-calming measures including center medians to prevent high-speed passing along West Marginal Way SW, a city-controlled street with some of the highest average vehicle speeds in the city, were paused indefinitely after a presentation to the freight advisory board prompted intense skepticism and fears of traffic backups. SDOT’s analysis of the proposed changes found “negligible impacts to traffic,” but that did little to assuage the freight board.

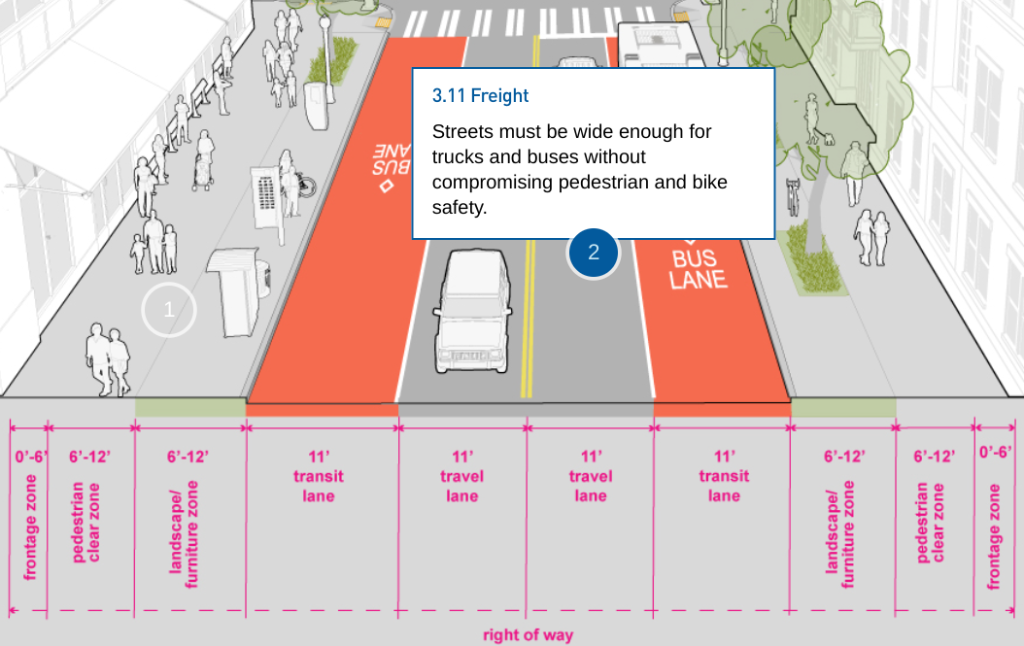

Just this week, the freight advisory board pushed back on plans to implement 10.5-foot lanes on a very short segment of a planned rechannelization of N 130th Street — a minor truck street, where trucks are 3% of overall traffic — in order to accommodate protected bike lanes. Seattle’s Chief Safety Officer Venu Nemani presented the board with information laying out how narrower vehicle lanes lead to slower vehicle speeds, but given the fact that Seattle’s own transportation design manual calls for 11-foot lanes even on minor truck streets, the argument was not well-received. It’s unclear whether SDOT will push forward or back off.

Even though this proposed change is included in a resolution, which has less force than a full city council ordinance, transportation advocates are taking it seriously as an impediment to some of progress Seattle has made in recent years around safety, as SDOT gears up to tackle some of the city’s most problematic streets.

“If safety is truly our city’s #1 transportation priority, the goal should not be to demonstrate that ‘through traffic will not be compromised’ (as in the amendment language), but rather to implement improvements will make everyone safer,” Gordon Padelford, the executive director of Seattle Neighborhood Greenways, wrote to city councilmembers this week, asking for a fix to the language.

Padelford pointed out the broad public support for safer streets.

“For example, the major truck streets of Aurora, Rainier, MLK, Lake City Way, and 4th Avenue S are the top five most dangerous streets in our city because they were historically designed to feel comfortable to drive at speeds we now know are dangerous,” Padelford added. “Changes to these and other streets may mean, at times, that through traffic in the hearts of our communities is a bit slower than it used to be — but that is a compromise Seattleites have said they are willing to make in polls and surveys.”

The resolution still needs to be approved by the full Seattle City Council, leaving time for a last-minute amendment that could scale back some of the strongest language in the text. But even if that happens, the episode underscores the disconnect that will continue to exist between encouraging freight mobility, which enables the entire city to access goods and services, and safety — at least so long as narrowing or eliminating general purpose vehicle lanes continues to be viewed as an existential threat to freight. Keeping streets exactly as they are right now isn’t going to make that conflict go away.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.