One in four Seattle blocks lack sidewalks, but a new bill would require that significant repaving projects add or repair them.

In 2016, after the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) repaved a long stretch of Greenwood Avenue N in North Seattle, between N 112th Street and N 125th Street, road users were left with an asphalt street that looked like-new. The repaving project was one of the first completed since voters had approved the Move Seattle Levy the year before, a transportation funding source that promised to invest $250 million into maintaining the city’s streets. But people walking or rolling on Greenwood Avenue wouldn’t have noticed much change, because the stretch of roadway, with one of the city’s most frequent buses, remained without sidewalks.

It would be another five years until the city was finally able to complete the installation of new sidewalks along Greenwood, using the dedicated funding for sidewalks earmarked in Move Seattle. But there was no requirement that the city coordinate sidewalk installation with the repaving project, even as the city’s existing Complete Streets ordinance does require that repaving projects coordinate to fill in gaps in the city’s bike network.

But that all could change thanks to a new proposal moving forward at the Seattle City Council.

The Council’s transportation committee got a first look Tuesday at a proposal that would require SDOT to build new sidewalks, and repair existing ones, whenever it completes a “major” repaving project on the adjacent street. Currently, the Cty’s Complete Streets ordinance falls short of making that an explicit requirement, leaving the issue to the city’s discretion. The legislation also hands SDOT additional reporting requirements around decisions to skip making sidewalk upgrades, in cases where it won’t become an explicit requirement.

The proposal was introduced by District 2 Councilmember Tammy Morales, who represents South Seattle, which is home to hundreds of blocks of missing sidewalks, with many more in very bad condition. Morales cited a number of mobility organizations and advocates who worked with her office to cocreate the legislation, including Disability Rights Washington, America Walks, and former SDOT Director Sam Zimbabwe.

“We know that there’s something like 4,000 miles of roadway in the city for cars, and about a quarter of it lacks sidewalks,” Morales said in a conversation with The Urbanist ahead of Tuesday’s committee meeting. “Whether it’s North or South Seattle, or just any part of the city that is lacking sidewalks, it creates a real safety hazard for our neighbors, but especially for folks who can’t drive. And it’s something that I think we have an obligation to address.”

SDOT already leverages its major repaving projects as an opportunity to repair sidewalks: a planned repaving of Denny Way through the heart of South Lake Union includes a $100,000 allocation from the city’s sidewalk safety repair program. The planned repaving of 15th Avenue NW and the deck of the Ballard Bridge includes a $500,000 add-on from that program. But sidewalk construction, an even more expensive and time-intensive process, is frequently put on a different timeline if it’s not postponed altogether.

Virtually all of Seattle’s large repaving projects, with a cost of over $1,000,000 — the main target of this legislation — occur on arterial streets. As of 2015, the last time a full-scale audit was done, around 14% of the city’s arterial streets were missing sidewalks, which amounts to nearly 2,000 blocks. By contrast, over 30% of non-arterial, or neighborhood, streets in the city lack sidewalks — nearly 12,000 blocks. Overall, nearly one out of every four blocks citywide lacked sidewalks.

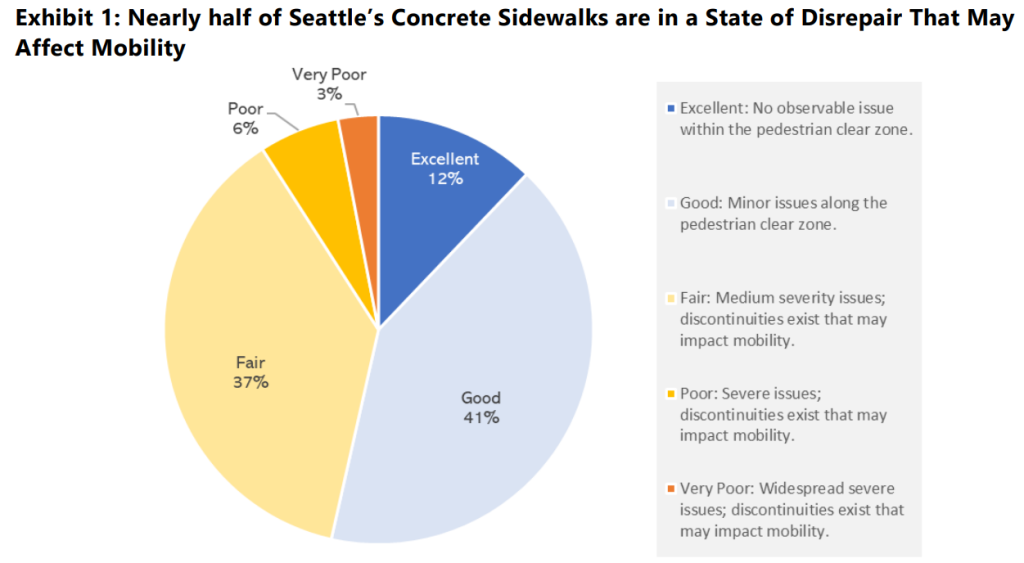

In addition to the staggering tally of blocks missing sidewalks, a 2021 audit of the existing sidewalk network revealed that almost half of the sidewalks in the city are in a “fair” or worse condition. In other words, only slightly more than half of the existing sidewalks in Seattle are in a state where full mobility can be ensured.

Minor repaving projects, referred to as pavement “spot improvements”, as well as routine pothole repairs completed by city street crews, would not be covered by this change in city law.

“Our cities have been made for roads,” Cecelia Black, an organizer with Disability Rights Washington’s Disability Mobility Initiative, told The Urbanist. “Roads have been the major priority of all our transit movement, and I think that when we build roads without sidewalks, it’s not just that we’re prioritizing cars over pedestrians and bicyclists. But also, we’re creating roads that are in complete contrast, and in contradiction to these huge Vision Zero goals and climate goals.”

Black pointed to the fact that sidewalks, unlike roadways, are currently left to the adjacent property owner to maintain.

“We have considerably more funding for road maintenance,” Black said. “But also, there’s a clear jurisdiction for roads. Which is just kind of crazy that a major piece of transportation infrastructure for pedestrians, there’s just no overarching jurisdiction responsible for sidewalks in that in a similar way. No other public space that we think of operates in such an ambiguous way, without any jurisdiction responsible for maintaining or regulating public spaces.”

The patchwork of jurisdictions in charge of sidewalks doesn’t just come up when it comes to sidewalk repair: it rears its head every winter when snow or ice blankets the city and people who rely on sidewalks need to depend on every single property owner (often including multiple city agencies) to clear a sidewalk. One failing link in the chain can block passage or lead to a dangerous situation. These issues have begun prompting increasing calls to shift responsibility for sidewalks, a city asset, away from the adjacent property owner and onto the City.

“I would like to see us shift our responsibility, and really also understand that perhaps we have too many roads in our city,” Morales said. “Maybe we can pedestrianize some of our roads altogether. I think I’ve been pretty vocal about wanting to see at least one pedestrianized street in every neighborhood, particularly around, commercial areas, so that we can start to reduce interactions in every community with cars.”

This change will not substantially alter the conversation about how to fill the vast majority of the city’s missing sidewalks along neighborhood streets, a conversation that’s largely centered around funding. Seattle is on track to have spent close to $100 million on new sidewalks over the nine-year Move Seattle Levy’s lifespan, with around half of that funding coming directly from the levy. With that, around 275 new blocks of sidewalks will be added, a mix of full concrete sidewalks and lower-cost alternatives like asphalt pathways that don’t require drainage improvements.

Morales wants this legislation to provide a new “benchmark” level of funding, without people who are pushing to expand the city’s sidewalk network required to show up every year at the city council’s budget hearings to get more funding allocated.

With only around 30 blocks going in per year, advocates are looking for the pace to accelerate and are looking for new forms of revenue to make it happen.

Transportation committee chair Alex Pedersen is touting the potential of transportation impact fees, which are levied on new development to ensure that “growth pays for growth” as a source of new sidewalk funding. Developers are already required to build new sidewalks directly in front of their projects, and housing advocates worry that additional fees on badly needed housing will stifle growth and push housing out of the city. Pedersen also wants to see impact fees replace a portion of the existing levy, a move that would not necessarily grow the amount of funding the City could allocate to new sidewalks.

Councilmember Morales does see the potential for exploring impact fees to fund sidewalks and take a bigger chunk out of the 11,000 block sidewalk deficit that the city has. “Some folks consider it controversial,” she said. “But I do think that it is something we need to consider, I think it is an important tool for us to raise revenue. And I will also say that I think of this as sort of a ‘both and’ — like I think this is important work to do, and we also have important work to do to reduce some of the other fees that are costs that our developers have.”

This update to the city’s Complete Streets ordinance, while it leaves that conversation around funding until another day, represents a big step forward when it comes to how the mobility of people who walk and roll, and depend on the city’s sidewalks, is treated when it comes to maintaining essential infrastructure.

“My hope is that this is the beginning of a new way to contemplate our interaction with the public right of way,” Morales said. “I really think that if we are going to meet our Vision Zero goals, if we’re going to meet our climate action goals, if we’re going to meet our interest in increasing community cohesion, the vibrancy of our neighborhood commercial districts, this is a really important way to do that: something that can can help meet all of those goals is to get people out of their cars and walking safely through their communities.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.