Late changes to add curving nine-foot-wide bottlenecks and remove bollards will hinder the new bike path.

On Seattle’s waterfront, visitors are now able to get a fairly good idea of the final form the long-planned redevelopment will take even though a final ribbon-cutting is still close to two years away. The Overlook Walk and the Aquarium’s new Ocean Pavilion is starting to really come into view at the north end of the project, and the final improvements around Colman Dock at the south end are starting to take shape. In recent weeks, the start of another flagship element that’s been central to achieving the long-promised vision for the project has been going into place: the new waterfront bike trail.

For nearly a decade, the plan for a continuous path for people on bikes to replace the former, unpleasant path that used to wind underneath the Alaskan Way Viaduct finally opening to the public has been worth the incredible amount of disruption for people who need to travel through the area. Finally, Seattle will have a waterfront bike path worth showing visitors, on par with facilities like the Hudson River Greenway in New York City. But now that several segments, not yet open to the public, have been constructed next to the new Alaskan Way, questions are coming up about how well the actual reality aligns with what had been presented in renderings and presentations.

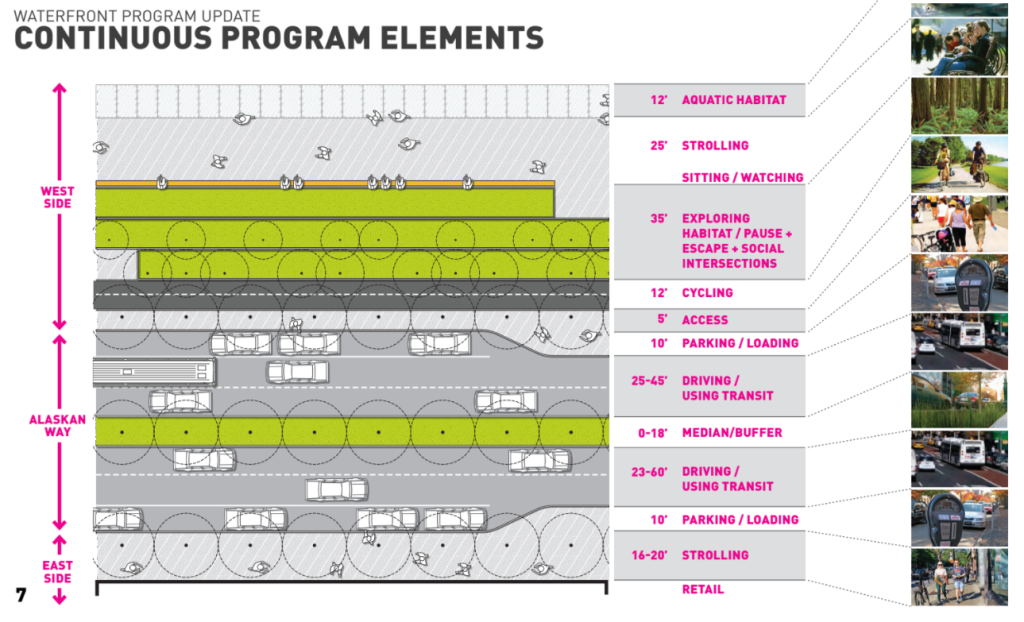

In early September, the City’s Office of the Waterfront posted a photo on social media of the new bike path. “What is dazzling, freshly paved and soon to be lined with native plantings?” the post read. “The Waterfront’s future two-way separated bike path!” But many noticed the photo seemed to show a fairly narrow path that included a sharp curve, prompting several people, including this reporter, to go out and measure the pathway. One segment of the asphalt portion of the path came in at nine feet. That’s a full three feet narrower than the 12 feet that has been touted on presentations coming out of the Office of the Waterfront since 2014. Combined with the curves the new pathway makes to jog away from Alaskan Way’s traffic lanes between intersections to accommodate space for on-street parking, it’s not hard to visualize how quickly the facility could become crowded.

This final design taking shape right now calls into question the degree to which the bike path, which had its design codified nearly a decade ago, lines up with the city’s goals around increasing bike usage. Side-by-side riding is basically off the table, and bike riders frustrated by the path may decide to utilize the wide pedestrian promenade being built closer to the water’s edge.

A Path Long in the Works

The idea of creating a dedicated bike path along the future waterfront dates to some of the earliest concepts for the redevelopment project. Materials from a 2012 “Waterfront into Focus” presentation, developed in partnership with James Corner Field Operations, fresh off the first phase of the Highline in New York City, show a path wide enough for side-by-side riding: other materials from around this time suggest a 16-foot pathway could be possible.

In 2014, the newly created Office of the Waterfront presented a unified program concept laying out exactly how space on the new waterfront would be divvied up after the Alaskan Way viaduct was removed. That’s when 12 feet became the promise — not a random number. The National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), released its urban bikeway design guide just a few years earlier, a move that had been considered a big step forward in design guidance for cities. It recommends a “desirable” minimum width of twelve feet, not including shoulders or buffers.

The next year, the Seattle Bicycle Advisory Board received an update on the Waterfront project, and during that meeting the 12-foot width for the “cycletrack,” as it was called at the time, came up. “This project is important because it is a north-south route that is flat with minimal intersections/crossings,” one comment recorded in the meeting minutes noted. “Therefore, SDOT should be expecting a lot of bike volume, so are 12-foot Protected Bike Lanes enough?”

The response described by the Office of the Waterfront was that “NACTO standards” (which are guidance) was used, but that the team would give the issue more scrutiny, and that there would be some flexibility with landscaped buffers on either side, a fact that doesn’t really seem to be true: most of the planters are being installed snugly against the bike facility within concrete curbs, making future expansion an expensive proposition.

That 2015 Bicycle Advisory Board meeting was also the one where a future connection to the rest of the downtown bike network was discussed, a connection that still doesn’t have a funding source or timeline eight years later. Making sure the waterfront project aligned with the city’s goals around making biking easier doesn’t seem to have been a top priority.

A 9- to 11-Foot Trail

In a statement, Iris Picat of the Office of the Waterfront and Civic Projects confirmed to The Urbanist that the city is counting the concrete curb on either side of the asphalt path as part of the trail’s width. “The width of the Protected Bike Lane ranges between 10 and 12 feet with the majority of the facility having a 12-foot width,” she said. “The areas that are 10-feet wide are for short segments at the intersections. In the image shared on social media, the width of the asphalt is 9-feet and there is a 6-inch wide curb on each side, which totals 10 feet. Since the curbs are level with the asphalt surface, they are considered as part of the overall available width between the planters.”

Guidance from the Washington State Department of Transportation, which is applied to mixed-use paths rather than dedicated two-way bike paths, is for the twelve-foot width to exclude shoulders. The flagship bike path along the Seattle waterfront won’t meet that standard.

The City also confirmed that some of the features seen as shortcomings were actually intentional design choices. “Note that the narrowing, as well as the curves provided near intersections, are intentional safety features that encourage bicyclists to slow down as they approach the crosswalks,” Picat said. “When traveling at slower speeds, bicyclists have more time to react to pedestrians in the crosswalk.” Alaskan Way’s vehicle lanes don’t include similar design elements to slow traffic, it must be noted.

More Last Minute Changes That Don’t Match Renderings

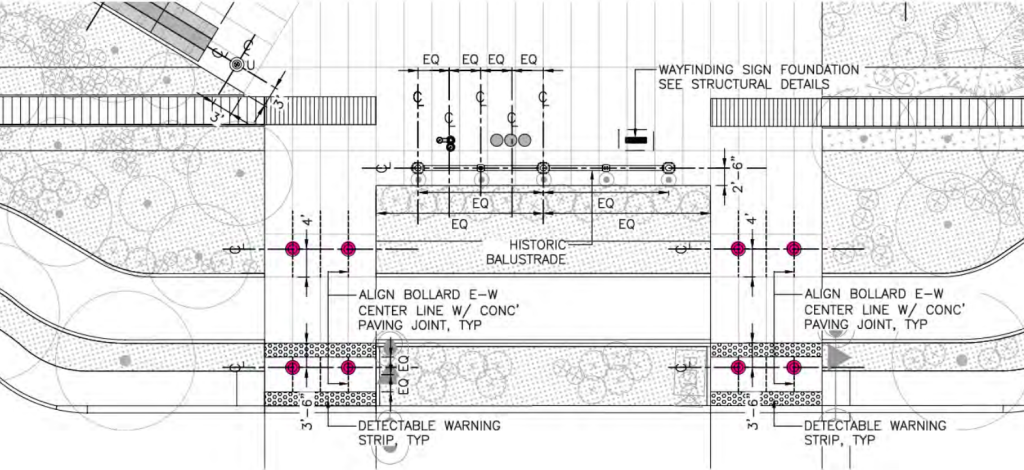

The width of the bike path isn’t a one-off in terms of elements of the project that look to be radically different compared to what was presented in renderings. Rendering after rendering, up until the 90% design phase presentation to the Seattle Design Commission in late 2017 — the last time minute details on the project were presented to the public before the long construction phase started — showed bollards separating entrances to the bike path from both the pedestrian promenade and the Alaskan Way street.

But no bollards are actually planned to separate the bike facility and the busy roadway, a frustrating continuation of Seattle’s allergy to using them across the entire city. After an eagle-eyed Seattle resident noticed no bollards being installed in real-life, the Office of the Waterfront confirmed that the illustration of bollards presented to the Design Commission in 2017 was merely to illustrate a “typical layout” of where bollards may be used, but that they are not “traffic rated,” i.e., intended to be able to block vehicle access. Bollards between the bike and pedestrian space will be surface mounted and installed closer to the completion of the promenade. “The bollards in the bottom row [of the illustration above] were deleted from the design plan before issuance,” they wrote in a statement.

Lack of bollards isn’t merely an aesthetic difference: their absence makes an event where a driver finds themselves on the bike trail a virtual inevitability, either by the driver’s error or their ill-intent. The narrowness of the trail, combined with the fact that the trail will be hemmed in on either side by planters, could spell disaster.

The question of how wide the final bike trail on the waterfront should be — and whether it should be protected by bollards to keep errant drivers from entering onto it — is a legitimate one worthy of a citywide conversation. But what appears to have happened here is a behind-the-scenes decision to go in one direction after all of the available information suggested otherwise.

Small details like those are adding up to many people’s perception that what they were shown over the past few years isn’t quite what’s being delivered now — and begging the question as to what else might have been changed at the last minute.

Drivers using the new lanes on Alaskan Way don’t have to wonder whether they’re standard widths for their cars, but the bike facility was treated separately. The fact that it won’t open to the public until next year, several years after the Alaskan Way roadway a few feet away, is a stark illustration of that fact in-and-of-itself.

Having a separated bike connection along the waterfront will be an appreciated upgrade compared to what existed before. But it also looks like Seattle’s waterfront plan took so long to come to fruition that what’s supposed to be a flagship element is set to be out-of-date before it’s even open to the public.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.