The issue of whether Seattle should impose a sizable fee on all types of new development to fund transportation network improvements is back in front of the city council, as several councilmembers who have long supported the idea try to move it forward before they leave office. Transportation impact fees, a tool authorized by the state legislature as part of the Growth Management Act, are levied by more than 70 cities statewide but have never been used in Seattle.

Under the auspices of asking “growth to pay for growth,” the legislature authorized impact fees to fund only projects that expand the capacity of the transportation network for users of any mode. But the issue of adding additional fees on new housing during a well-identified affordability crisis is causing additional scrutiny of the idea.

The proposal on the table now would update the city’s Comprehensive Plan to include specific details on how a transportation impact fee would be implemented and which projects could get funding, with any vote to actually adopt impact fees occurring down the road. But the discussion is happening against the backdrop of an active appeal of the proposal, with the appellants telling the city’s Hearing Examiner just last week that they don’t believe the City did proper due-diligence around the proposal.

That appeal is essentially a replay of a similar appeal from 2018, brought by the same shadowy group calling itself the Seattle Mobility Coalition. It argues the City cut corners in conducting environmental review of the overall citywide impact of impact fees. During last week’s hearing, a number of local housing developers testified and made the argument that the transportation impact fee proposal will add to the cost of housing and slow development, to the detriment of the city.

Bill sponsors Alex Pedersen and Lisa Herbold had originally scheduled an official public hearing this week to receive comments on the proposal, but were forced to cancel given the fact that this appeal is still active, with a ruling not expected until deep into the council’s budget season this fall.

Councilmember Herbold called the move a “small procedural step” that still leaves the issue of actually implementing impact fees to another time and a new set of councilmembers, but it’s not exactly clear why the city council couldn’t take that step if the body decided to move forward. The city’s Comprehensive Plan already says the city should consider the use of transportation impact fees, and the transportation project list will likely be updated as priorities change with a new council.

And it will be a majority-new city council since four sitting councilmembers are not seeking reelection and a fifth (Teresa Mosqueda) appears poised to win a King County Council seat, vacating her seat. Statements on the campaign trail from leading council candidates suggest there will likely be more skepticism of the entire concept next year, with candidates like D3’s Alex Hudson and D4’s Ron Davis strongly coming out against impact fees.

“They are perverse, raising the cost of supplying a good with significant positive environmental, economic, and social justice externalities,” Davis wrote to The Urbanist’s elections committee earlier this year. Davis led the field with 45% of the primary vote, suggesting he’s the leading contender to replace Pedersen on council.

The push for transportation impact fees is also tied to the fact that Seattle’s current nine-year transportation levy, dubbed, Move Seattle, is set to expire next year. Transportation Committee Chair Pedersen has been fairly adamant that the city move forward with implementing transportation impact fees as a replacement for at least a portion of the levy, currently funded entirely by property taxes.

“In the spirit of progressive tax reform — which is long overdue in Seattle — imposing this one-time new fee on just new for-profit real estate development could, in turn, enable City Hall to LOWER an ongoing expense for everyone’s housing: the property taxes charged to everyone for future transportation projects,” Pedersen wrote in a blog post on his council website earlier this year.

But an impact fee that discourages housing growth in Seattle, making sprawl more cost-competitive and drives up commute times would put more demand on the region’s transportation system overall, defeating the entire purpose of the impact fee program.

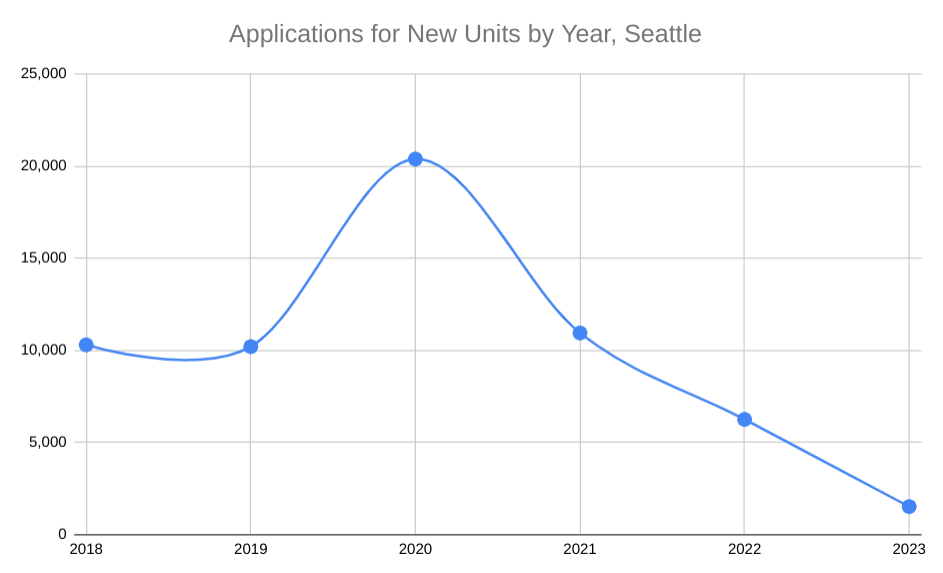

Housing Applications are Way Down in 2023

The new discussion about this potential source of transportation funding is happening at a time when city data shows the pace of development is slowing considerably. Permit intake data from the Seattle Department of Construction and Inspections (SDCI) shows that new applications for housing are at a fraction of the levels that they had been in recent years, as high interest rates continue to make borrowing to finance projects less and less feasible.

Applications for new units of housing through the second quarter of 2023 totaled just 1,514, a 62% decline year-over-year for that period.

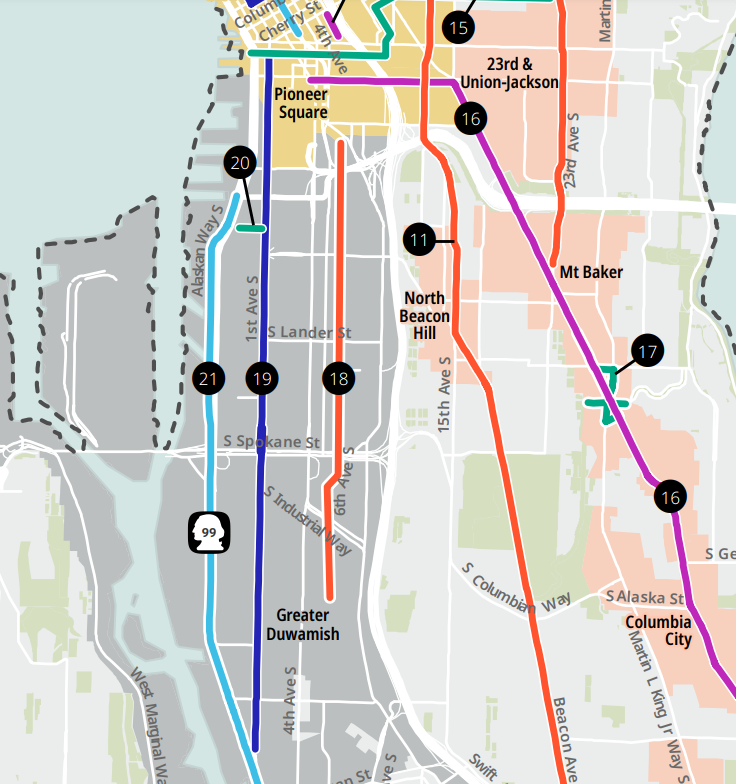

At Wednesday’s meeting, a number of housing developers spoke to the chilling effect a new fee could have right now. Pat Foley of Lake Union Partners, developer of the Midtown Square project at 23rd and Union — a project that the Seattle Times recently noted “offer[s] hope for Seattle’s future” by allowing the city’s cultural roots to have a new home — noted impact fees would have rendered that project infeasible.

“What I will tell you is if the impact fees that are being proposed were in place when we started that project a few years ago, we wouldn’t have built that project. Social impact projects like that would be done… we just can’t take the hit, there’s no more room,” Foley said.

State law allows jurisdictions to exempt affordable housing projects from impact fees, but the proposal has not defined what level of affordability would qualify for an exemption.

“I recognize that the reasons for the decline in projects that we’re seeing are complex,” Councilmember Mosqueda said at Wednesday’s committee meeting. “I do wonder about what impacts we would have if we were going to layer on a new fee.”

Mosqueda didn’t go so far as to say that the proposal shouldn’t move forward, but did want the city to consider the most up-to-date information on new units coming online. “The concern that I have is wanting to see any real-time analysis of potential impacts on housing production, given the impact of the pandemic on housing production and the slowdown that we’ve seen…all of these things have been identified as important factors for why we need additional funding, but we also need additional housing.”

A Project List from 2018

The big thing that the bill in front of the council right now would do is adopt an official list of projects that could be funded by a future impact fee. Only transportation projects that add capacity — for any mode of transportation — are eligible to be funded through transportation impact fees, and a project has to be specifically listed in the Comprehensive Plan to receive that funding.

The laundry list of projects developed for the city council’s impact fee proposal includes a number of multimodal corridor projects, like upgrading Lake City Way, Rainier Avenue, or Jackson Street into a “complete street” — though it’s not exactly clear what that means. It also includes multiple projects aimed directly at increasing freight and general-purpose vehicle capacity, including expansion of city streets around the I-5 ramps at 6th Avenue, truck improvements to S Massachusetts Street in SoDo, and vague improvements to First Avenue through Downtown and SoDo.

The current way the impact fee proposal is structured, developments in specific areas of the city do not directly fund projects related to expected capacity needed in that area. A new townhouse in Ballard, for example, could be charged an impact fee that funds signal upgrades or truck aprons in SoDo. On its face, that appears to be a big hole in the “making growth pay for growth” argument used to justify the policy. And then there’s the fact that the project list doesn’t seem to be aligned with the city’s Climate Action Plan and its goals around reducing emissions and vehicle miles traveled.

During Wednesday’s hearing, city council central staff noted that the list the city is moving forward with is largely the same one that was developed a half-decade ago by then-transportation chair Councilmember Mike O’Brien, who left the council at the end of 2019. While the list had been updated to do things like remove upgrades to Delridge Way SW that were completed as part of the RapidRide H project, it still includes Madison Street bus rapid transit, a fully-funded project that has been under construction for nearly two years.

The project list is not aligned with any of the projects in the draft of the Seattle Transportation Plan, underlining why the next council will likely want to take another look at what’s included.

The debate around whether impact fees are appropriate for Seattle, especially given the current development market, may clarify the issue for several councilmembers who may be on the fence. However, we can likely expect the policy debate to be repeated under the next version of the city council, raising the question of whether this is the best use of time for an 11th-hour city council.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.