The proposal resurrecting Route 47 brings deeper cuts to Routes 10, 11, and 49, which seem unlikely to curry support.

King County Metro is wrapping up its second round of proposed bus restructures around the forthcoming RapidRide G Line. In September 2024, the new line is supposed to launch with very frequent bus service along the Madison Street corridor between 1st Avenue in Downtown Seattle and Martin Luther King Jr Way in the Central District. As part of this, Metro is proposing adjustments to existing service on five bus routes that serve Capitol Hill and First Hill.

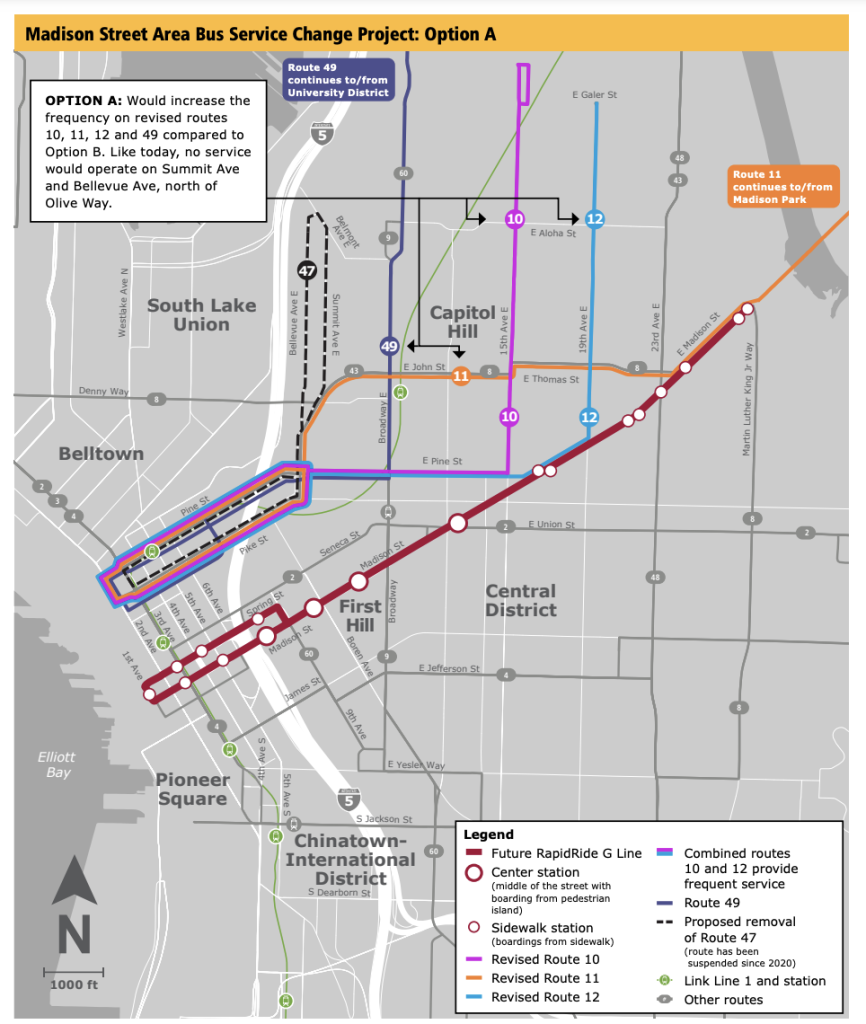

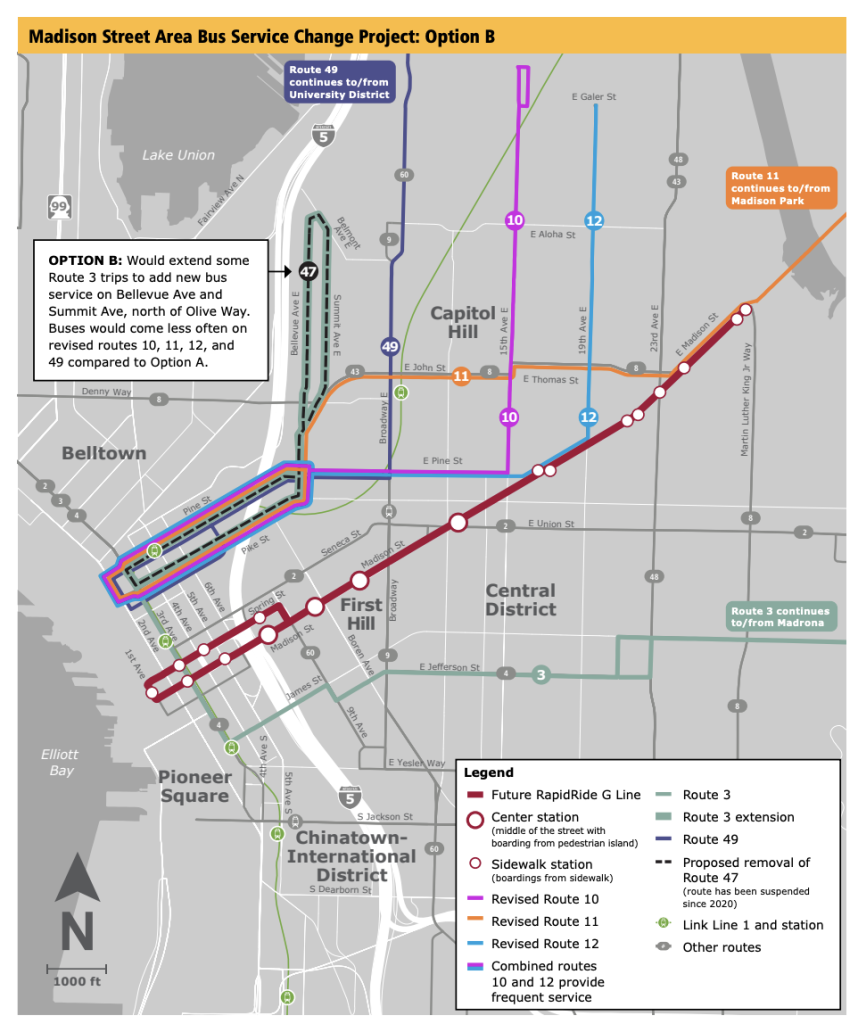

In this phase of the restructure process, Metro is offering two competing options. One is essentially the proposal shared in March (Option A) and the other would restore a suspended route (Option B). Generally speaking, both alternatives would reduce service in various parts of Capitol Hill and the U District, with the most noticeable impacts outside the Pike/Pine corridors. Underpinning both alternatives, too, is a move of Routes 11 and 12 off Madison Street west of 23rd Avenue E so as to deploy the RapidRide G Line on the street in their stead with higher frequencies as a single, direct service to the waterfront.

According to Metro, there was strong interest in the first round of public feedback to restore service on the long-suspended Route 47. That route is over a century old — a tram line turned trolleybus route — connecting the dense shoals of Capitol Hill. During its life, it ran on a circuit via Summit Avenue E and Bellevue Avenue E north of E Olive Way to Downtown Seattle, but was suspended in 2020. It was a short route, but it served a highly populated, hilly area with faster access to Downtown Seattle than alternative services.

As a result of public feedback, Metro is proposing restoration of Route 47 in Option B by extending some Route 3 trips to serve the corridor. The catch, however, is that service options for all other non-RapidRide G Line bus routes would be worse off than under Option A, which doesn’t restore Route 47.

It’s hard to see the Route 47 proposal as an honest attempt by Metro to restore the service, all but guaranteeing its continued demise.

This bus restructure is very challenging because Metro is largely operating under its policy to make annual service hour neutral changes. A small infusion of an additional 26,000 annual service hours is slated to be deployed into the restructure area, but most of that is going to the RapidRide G Line to meet its frequency targets required under a grant agreement with the Federal Transit Administration.

In March, fellow reporter Ryan Packer explained the general frequencies that will be provided on the RapidRide G Line in light of the agreement.

“[The] agreement commits Metro to providing six-minute service — 10 buses per hour — between 6am and 7pm, every day except Sunday. That’s a big increase for trips along Madison itself compared to the routes the G Line is replacing, the 11 and the 12,” Packer wrote. “After 7pm, service is kept very close to where it is now, with four buses per hour. (So make sure to leave for your 7:30pm show at the 5th Avenue Theater a little early.)”

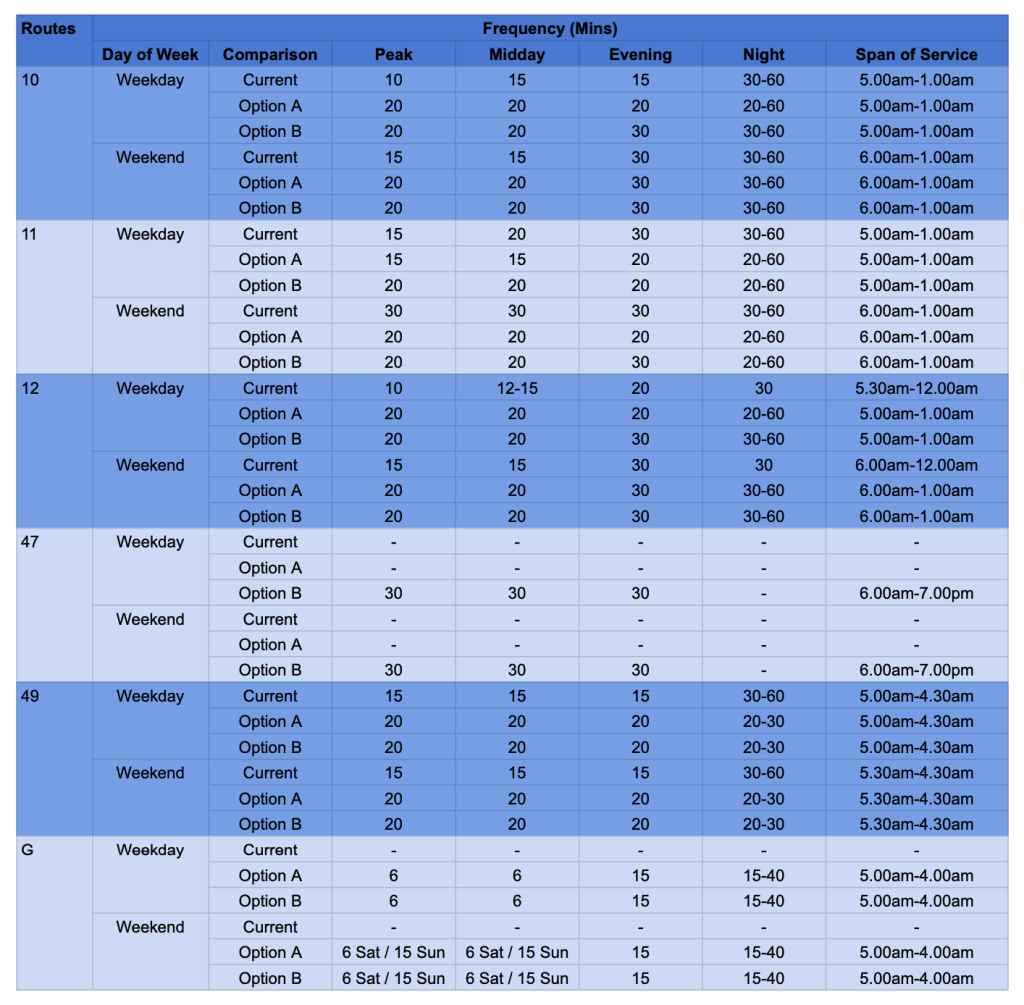

With the information Metro has been providing, it’s hard to really parse how the proposals stack up against today’s service levels. To illuminate that, The Urbanist put together a table comparing current weekday and weekend frequencies and spans of service against the two alternatives now on the table.

To be sure, there are elements of the proposed alternatives that are better than the existing schedule, but they are relatively few and mostly during nighttime periods, though midday frequencies on Route 11 are a little better in Option A than today.

On balance though, frequencies during most peak, midday, and evening periods would get worse by 5 to 10 minutes on Routes 10, 11, and 12, often offering 20- or 30-minute frequencies instead.

The impacts of the restructure proposals really hit hard outside the Pike/Pine corridor. Riders along Route 49 near Broadway E, 10th Avenue E, and Harvard Avenue — all areas with substantial levels of multifamily housing — would see a 25% reduction in daytime and evening service. That’s similar for riders of Route 10 along the very dense, mixed-use corridor of 15th Avenue E north of E John Street. But for Route 12 riders north of Pike/Pine, the daytime and evening service cut would be more in the 33% to 50% range on weekdays and 25% on weekends.

There are some other tradeoffs riders will also have to consider with the proposals.

- Route 10 would no longer provide direct access to Capitol Hill Station via E John Street and service along E Olive Way. But it would mean that riders would have more direct service to the heart of Capitol Hill at Pike/Pine and it restore bus service on 15th Avenue E south of E John Street — a dense, mixed-use corridor in its own right.

- Route 11 would be routed away from Pike/Pine, requiring a transfer to reach if east of Capitol Hill. But those same riders would have direct access to Capitol Hill station as a result.

- Route 12 riders north of E Madison Street would lose their one-seat ride to the Colman Ferry Dock and downtown office core. In the process though, they would gain more direct access to Pike/Pine and the downtown retail core.

Some of these tradeoffs might be worth it, but the reduction in service levels does make them a harder pill to swallow. With Metro continuing to cut back service in September and overall service reliability being poor, it’s very hard to say if the promised service in the proposals would actually be attained — though a new contract with Metro staff could be a saving grace in attracting more staff.

But more fundamentally, this restructure around new rapid transit — much like the Lynnwood Link restructure for the north end — really illustrates the need to reform Metro’s service guidelines which direct bus restructure processes. Bus restructures spurred on by new rapid transit lines shouldn’t result in local transit network service reductions. It violates the contract that has been made with riders and voters that new rapid transit lines are supposed to expand the pie, not eat away at it. At some point, riders and voters will catch on that new rapid transit investments aren’t delivering on that promise and the political consequences to transit is not likely to be good.

Ultimately, shiny new rapid transit doesn’t mean a lot if you can’t get to where you want to go in a timely manner.

Riders and transit advocates should provide feedback to Metro through RapidRide G Line restructure survey (open through August 31). Riders and transit advocates would also be wise to contact the King County Executive, King County County Council, Regional Transit Committee, and Metro via email about their concerns with Metro’s restructure processes and pending restructures.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.