In 1972, the City of Seattle asked a group of citizens, anyone who wanted to attend a series of meetings, to work together to produce recommendations for ways that the City could improve in the decades to come before the end of the century. That same year, Seattle voters decided to officially cancel plans for another north-south highway through the City and to grant King County Metro authority to expand the city’s bus system. The recommendations that this group, called the Seattle 2000 Commission, released one year later offered pretty clear and straightforward ideas on how the Seattle of the future should approach transportation: increase mass transit, make it easier to walk and bike in the city, and de-prioritize the role of the private automobile.

“Individual motor vehicles, in their consumption of land and energy resources, imposition of visual blight and physically dividing barriers, creation of vehicular congestion, noise, air pollution and more tangible hazards to life and safety, are the most disruptive present means of transportation in the city,” that final report stated.

Fifty years later, these citizens’ views seem pretty close to the majority of today’s Seattle residents. Over the past year, as the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has been conducting the broadest set of outreach work that has been done in several decades around priorities for transportation in the city, the results have been pretty overwhelming. One online survey the department ran about a number of potential future pathways the city could choose to improve the transportation network garnered a stunning 95% response for the most ambitious option out of more than 3,200 votes.

At an in-person open house this January, no attendee supported any option other than “rapid progress.” Making space for pedestrians on the city’s streets was the number one most responded-to option when participants were asked which specific actions they’d support, while readying the city’s streets for “emerging technologies,” like autonomous vehicles, ranked last.

All this feedback has been collected to update the city’s overall transportation plans, and the result, the Seattle Transportation Plan (STP), became available for public review in draft form Thursday. But, like the many plans produced over the past few decades seeking to revolutionize Seattle’s planning, the key question is not really how ambitious the plan is, but whether it can be carried through into implementation. For example, the ambitious 2015 Move Seattle Levy set up a transformative plan that matches the ambitions of Seattleites only to be undercut with delays and a stubborn political reality that could set things back even further.

The Seattle Transportation Plan Itself

Set to take the place of Seattle’s currently siloed modal plans, the Bicycle, Pedestrian, Transit, and Freight master plans, the draft plan is plenty ambitious. “The STP is based on fundamental commitments that: Put safety first on every street and at every intersection,” it states, continuing the list. “Prioritize streets differently than in the past. While personal vehicles have a place, we will prioritize space-efficient travel options for moving people (transit, biking, walking, and rolling).”

The so-called “key moves” in the plan are all likely to have broad support, especially based on the city’s previous rounds of outreach. Framed under the umbrellas of safety, equity, climate, mobility, livability, and maintenance, many of these are already well underway. The top action under safety, reducing vehicle speeds, is one that seems to have broad support and has shown results in the real world. And it’s hard to argue with improving air quality and health outcomes by promoting more sustainable travel options.

But below the surface, future conflicts are not hard to find. A freight-focused project that would upgrade signals along N 85th Street to “provide consistent travel times on [the] freight corridor” doesn’t easily mesh with the idea of putting safety first on a corridor that connects multiple growth centers and urban villages. The same goes for 4th Avenue S, one of the city’s most dangerous streets and an area where traditionally SDOT has met considerable resistance to making street changes.

While the conflicts between different visions of how Seattle’s transportation system could evolve were more apparent when there were entirely separate plans, combining everything into one doesn’t actually resolve that conflict. There are signs of hope that changes are being implemented within SDOT that center safety even more, but the words in the plan on their own don’t guarantee that they will win out.

The Plan’s Nuts and Bolts

The most important elements of the plan are buried in its 610-page technical report, which gets down to brass tacks on some of the changes SDOT proposes making internally that will make the city more well-positioned to achieve the plan’s ambitious goals. It’s also here where we see some of the things that may hold the department back.

The element of the plan focused on public transit proposes a framework around the addition of transit-only lanes, which until now have been largely moved forward on a one-off basis. A set of tiers based on the number of buses using a street would mean 24/7 bus lanes would only be “expected” on streets with 400 scheduled bus trips per day, with streets seeing between 200-400 buses would only be expected to see peak-only bus lanes. “Transit should be a competitive mode of travel, while still maintaining mobility for other modes,” the plan says of those “medium priority” streets, which include Rainier Avenue south of McClellan Street, where the city’s second highest ridership bus, the Route 7, runs.

This policy seems behind the direction that Metro wants to go, which is toward an all-day system, where buses need to provide competitive travel times at all times of day, and it also seems inconsistent in that it looks only at sections of corridors and not entire transit lines, where a tricky segment could hold back an entire high-ridership bus line.

How the STP Envisions the Future Bike Network

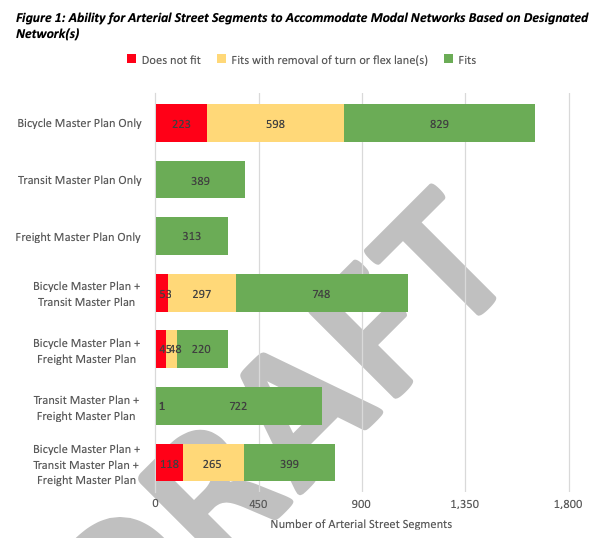

The technical roots of the Seattle Transportation Plan go back to 2020, when SDOT’s planning division tried to find a way to resolve potential conflicts between future uses of road space on a citywide level, looking at where the existing separate plans all envisioned using the same space. As the documentation revealed, this was mostly a “conflict” between the city’s ambitious 2014 Bicycle Master Plan and… everything else, mostly parking. On a virtually insignificant segment of the city’s roadways were future bikeways in conflict with transit, or walking, or transit plans. That work underlined how the primary barrier holding the city back isn’t street space, but timidity.

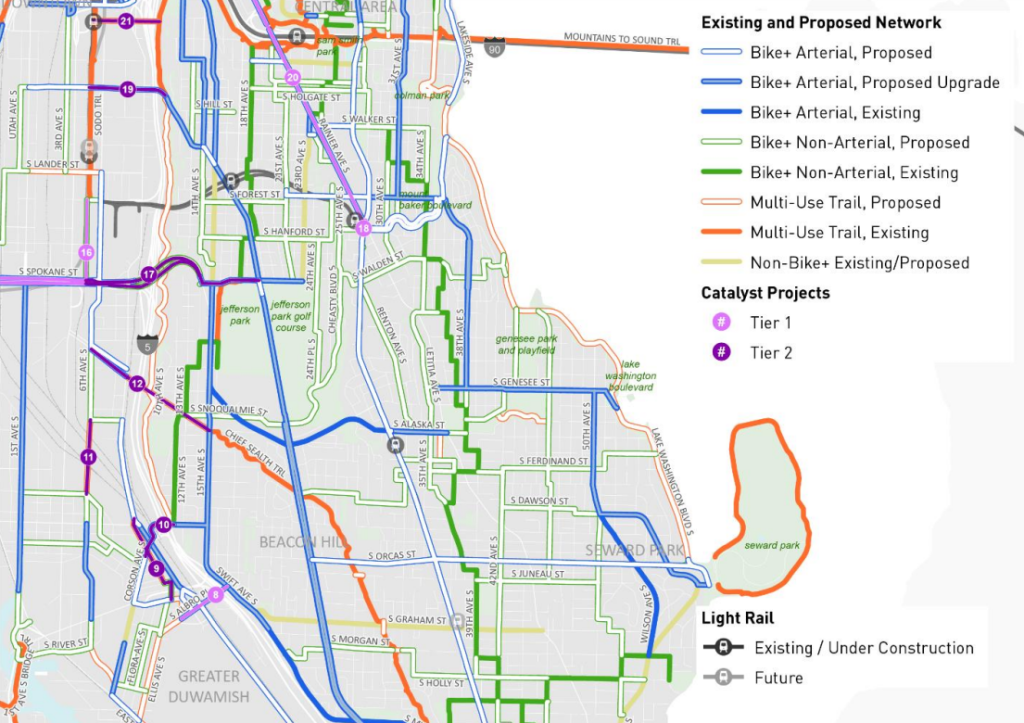

The new network maps in the Seattle Transportation Plan do envision bike facilities on a significant number of arterial streets throughout the city: If the entire network as laid out were built, it would be transformative. This is true of the 2014 Bicycle Master Plan, as well. But what the STP network map does do is include a significant number of street segments where the idea of bike facilities has now been traded away, shown on the draft maps as yellow lines.

“Some roadways are important connections for people bicycling and using e-mobility devices, but right-of-way is so constrained that an [All Ages and Abilities] bike facility is not feasible,” the plan states.

South Graham Street, directly connecting with a planned Sound Transit infill station, is one such street where the roadway width is so constrained that bike facilities aren’t worth pursuing. The question of whether S Graham Street needs to stay an arterial street if it can’t accommodate all modes is another direction the city could go, but with this plan it looks like the door will be closed on the idea of bike facilities instead.

The plan also includes a number of “catalyst projects” with the potential to change the game in terms of how the city’s walking and biking network operates via a big project. Rainier Avenue, south of Mount Baker Station, one of the city’s biggest opportunities to reallocate street space, is one such project in the plan. That means moving it across the finish line will be a much heavier lift, but the gains have the potential to be oversized as well.

A line on a map doesn’t make a project happen, as Seattle saw in places like 35th Avenue SW and 35th Avenue NE. The best the plan can do is leave open possibilities and frame future action as in line with goals that everyone supports.

Codifying People-Focused Streets Within Seattle’s Transportation Planning

With separate bike, pedestrian, and freight plans, Seattle hasn’t had any framework prior to this for street-spaces that are focused around things other than throughput: spaces where the point is for people to linger, to gather, to enjoy. As a result, some of the city’s most well-loved places have existed as one-offs in the transportation network. There’s nothing you can point to, for example, that lays out how a street like Occidental Avenue S in Pioneer Square, which was pedestrianized for two blocks in the 1970s, fits into the city’s transportation framework. The same goes for the block of Franklin Avenue E in Eastlake where kids and parents can gather before or after school at nearby TOPS K-8 but where vehicles are not allowed.

Developing a framework for creating people-centric spaces where moving vehicles is not the priority is a step to be celebrated. Again, it can’t make the projects happen on their own.

There are lots of reasons to be optimistic about the momentum that the Seattle Transportation Plan can provide as the city gears up to renew its transportation levy and tackle the big challenges facing it over the coming years. But there’s also plenty of cause for caution, in a city where the well-assembled plans often end up in drawers just a few years after they’re completed, never to be heard from again.

Review the plan and comment via SDOT’s online engagement hub.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.