The project is a big step for Snohomish County’s largest city, which has been slow to expand safe bike and pedestrian infrastructure.

This spring, city crews working on a repaving project put down something that hadn’t been seen before in Everett: green paint to mark a bike lane and some concrete barriers for that bike lane near the intersection of two of the city’s busiest roads. Madison Street, one of the most useful corridors when traveling east-west in Everett, previously had some painted bike lanes, but they didn’t even connect along the entire street, leaving bicyclists trying to fend for themselves at the major intersections.

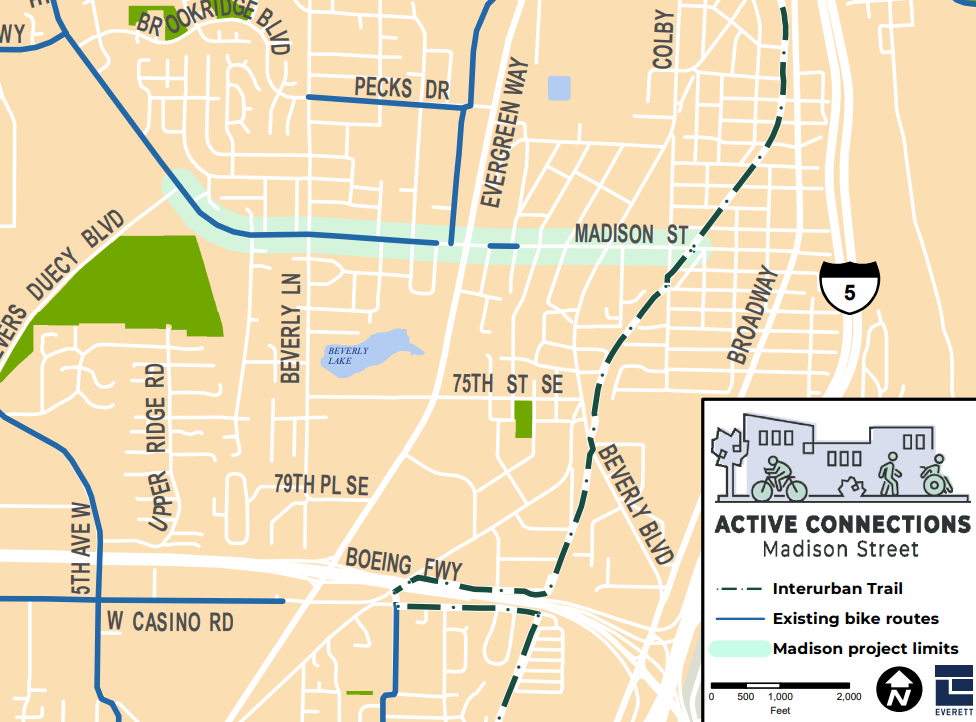

Now, people wanting to travel between Everett’s segment of the Interurban Trail, past Evergreen Way where Community Transit runs its Swift Blue Line, and further west toward neighborhoods like Harborview/Seahurst/Glenhaven and Mukilteo even further beyond, won’t have to contend with sharing a lane with drivers.

The bike lane is far from perfect: The buffered bike lane features no physical barriers except for a brief stretch separating riders from turning vehicles at Evergreen Way, and the design implemented maintains on-street parking on the other side of the bike lane for most of the corridor.

For its shortcomings, the project is a big step for Everett, Snohomish County’s largest city of 114,000 people, and one that has been slow in expanding safe bike and pedestrian infrastructure. Over the next two decades, Everett is expected to add nearly 70,000 residents, close to one out of every four new residents anticipated in Snohomish County as a whole. Expanding the city’s safe biking and walking networks clearly needs to be a part of that growth strategy.

“We’re definitely getting started,” Everett Councilmember Liz Vogeli told The Urbanist. Vogeli sees Madison Street as sending a signal that Everett is making space for bicyclists. “It’s definitely a visual for people in their vehicles to see that something is happening for bicyclist safety. That’s, I think, a big deal.”

Madison went through considerable pushback from nearby Everett residents before it was ultimately implemented. Last year, a veteran’s group with a clubhouse on the corridor had over 120 of its members on record in opposing the bike lanes, citing potential loss of parking. As a result, the City went with a design that removed the center turn lane along Madison instead of removing-on street parking.

“There was a lot of outreach to the businesses and homeowners making sure that we could get all the way over to Broadway, by not taking out parking, because people are really concerned about that,” Vogeli said. “It seems to me, with the outreach, that a lot of people actually got what they wanted. If Madison works for the people that live and work there, I think that will create more acceptance for a future project.”

Not everyone sees the new bike lanes as a huge step forward. “While I appreciate the buffered bike lanes, it’s just another missed opportunity for them to really turn the page and say, hey, we’re actually going to approach infrastructure differently,” Colton Scott Davis said. Davis is an Everett resident pushing the city to make more space for biking. “I feel like they still did a disservice to us, because there was the opportunity for them to remove parking on the side of the street…there literally is no logical reason to keep the parking intact,” he said.

He points to nearby Broadway, where the city is currently repaving one of its busiest streets and leaving the design largely the same, with five travel lanes, curbside parking, narrow sidewalks, infrequent pedestrian crossings, and no bike facilities.

“I just think they were quick to decide to repave without thinking about the long term consequences of what that repaving means and just how many people are actively using Broadway to get to and from where they need to go,” Davis said. “It’s obvious that people are using bikes on Broadway because you have to cross Broadway to get to Everett station, people are coming from the station to get into downtown…and there wasn’t an opportunity to even really provide any feedback on the current plan for it.”

Instead, Everett is planning a shared-use path that winds between Everett Station and downtown’s major events center, Angel of the Winds Arena, with no ETA for an extension further into downtown.

The biggest barrier standing in the way of Everett making progress is likely the city’s Bicycle Master Plan, now over 12 years old. While it envisions a citywide bike network, it doesn’t prescribe any on-street bike lanes that include full physical barriers between people biking and people driving, instead focusing on widening existing paint bike lanes and painting more bike markings.

The City of Everett pointed to the plan as the main reason Broadway is staying as it is even after a major repaving. “There is not a bike project for this section of Broadway in the Bicycle Master Plan (BMP), so we were not able to evaluate it for bike facilities,” Kathleen Baxter, a spokesperson for Everett’s Public Works Department, told The Urbanist. “Building bike facilities on Broadway would require a significant change to the way Broadway currently functions. Without a project from the BMP guiding us, and without a connecting bike facility on Broadway, it would not be advisable to make such a change during routine maintenance of our roads.”

“The pavement maintenance project does not include funds to make upgrades to pedestrian facilities,” Baxter added. “The scope of the project is limited to replacing the pavement, traffic signal loops and striping, and upgrading the curb ramps. Typically it is not feasible to build facilities outside the scope of a project.”

“The Bike Master Plan badly needs to be updated with a safe network of neighborhood greenways, designed at 15 to 20 miles per hour, and protected bike lanes, as opposed to just kind of low quality bike routes across the city,” Brock Howell, executive director of The Snohomish County Transportation Coalition, which advocates for transportation improvements throughout the county, told The Urbanist. But he sees Madison Street as a progress point that Everett will build on. “The next version, the next buffered bike lane and protected bike lane will be an improvement over this one,” he said.

Councilmember Voegli agrees that the bike plan badly needs updating, noting that the old plan isn’t aligned with the current or projected future levels of population growth in Everett. “The amount of additional vehicles and people within the city of Everett and who traverse through the city of Everett has changed so much that [the bike plan] needs to be reworked for A, the amount of people, and B, new and improved [facilities]…not just paint on the roads,” she said.

Change may be coming even sooner than the city is able to schedule a full update of the Bicycle Master Plan. Earlier this year, Everett was selected as one of six regional jurisdictions provided funding to create a road safety plan, in coordination with the Puget Sound Regional Council. The $788,000 grant will fund a plan to develop “holistic, well-defined strategy to prevent roadway fatalities and serious injuries,” according to the U.S. Department of Transportation, which is providing the funding. Of course, any safety plan won’t be able to make tough choices for Everett leaders around reallocating street space, as advocates continue to push.

Despite slow progress and some significant missed opportunities, Everett looks poised to be able to make some significant leaps forward within the next few years, if the city is able to build on what’s been successful. That progress can’t come soon enough.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.