Transit: Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?

Transit has been getting some tough breaks lately in the Puget Sound region and across much of the United States. Projects are behind schedule and overbudget, and agencies are struggling with labor shortages and with attracting riders back following the shock of the pandemic. Many have significantly fewer riders than they did pre-pandemic and have trimmed service.

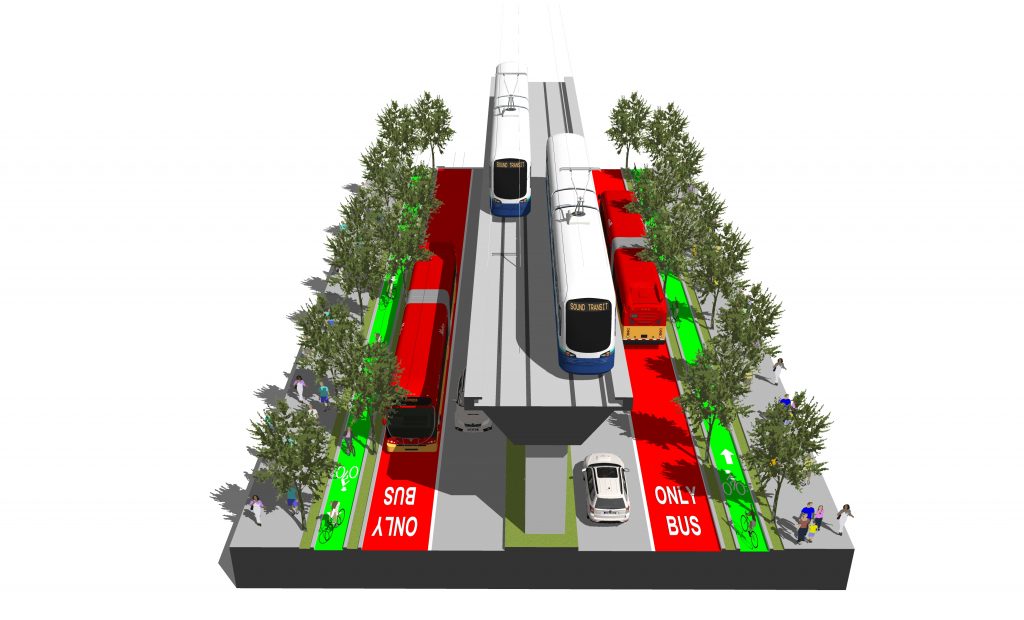

Oddly though, some potential solutions to this downward spiral of transit momentum are not being attempted, let alone seriously contemplated. For overbudget transit expansion projects, that can mean jettisoning road widening that has been worked into the scope. Instead, we can simply put the bus lane or light rail guideway right there in the road right-of-way in place of parking or that sixth, seventh, eighth, or ninth lane of car traffic. American roads are really quite wide!

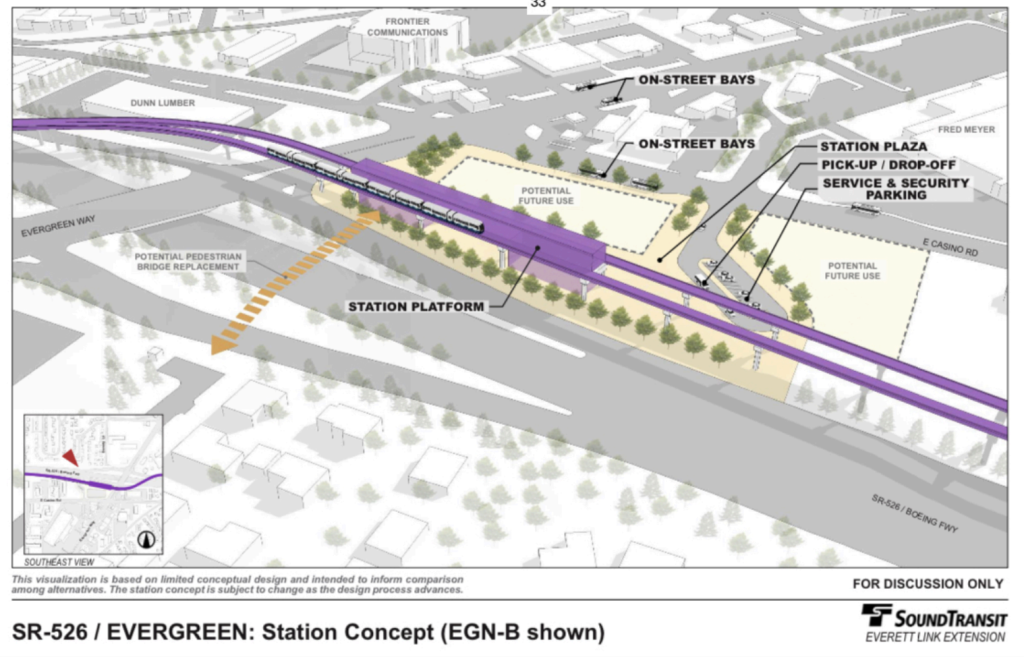

Sound Transit Boardmember Claudia Balducci has made this point repeatedly, such as at a June meeting when the board grappled with a ballooning budget for the Everett Link light rail extension and an off-the-rails Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) that could trip up the project down the road.

“We have a lot of takings in order to do elevated [guideways] that could be done in the roadway,” Balducci said. “My question is this: By taking this action today, are we still able to look at those corridors through the DEIS process, and consider options that would follow those same alignments, but might be narrower and limit the takings and consider the use of public right-of-way where that is possible and appropriate?”

Unfortunately, neither the agency nor many of her colleagues appear keen on pursuing this line of inquiry, which could ultimately save them billions while improving outcomes.

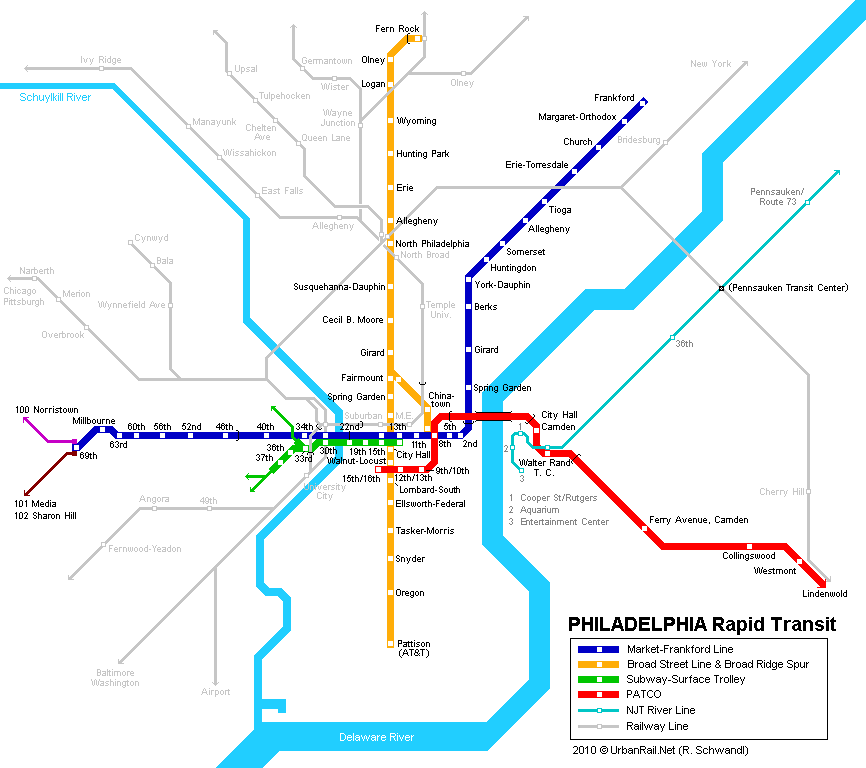

Taking a lane or shoehorning a line right above or below an existing street is how we used to build transit when America was a pioneering leader in developing rapid transit systems in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. A trip to a legacy metro system will confirm this — as a recent trip to Philadelphia did for me. Elevated rail is integrated into Philadelphia’s urban fabric, fitting in nicely in some of the most iconic and beloved Philly neighborhoods.

In general, elevated rail is much cheaper to build than underground rail, which is a big advantage for transit agencies facing a budget crunch like Sound Transit and many of its peers. It’s also easy to navigate and much more intuitive and scenic for riders, since they can see which neighborhood they are in. Philly has also done a good job of pairing stations with bikeshare docks to improve station access.

Since Philadelphia has been a big city for a long time, 200 years longer than the comparative upstart Seattle, they built so many rail lines that one of them has now been converted to park space. Currently, that park only spans a few blocks in the Callowhill neighborhood, however the city’s vision is to convert three miles of the unused rail line into a park – double the length of New York’s High Line in Chelsea.

Once the elevated right-of-way through a dense urban space has been created, they tend to be highly valued and cities come up with dynamic uses for them even after the initial one has run its course, like Philadelphia is doing now. Maybe there’s also a case to bring back a rail line along that route, but a linear park is pretty cool, too.

So why did cities stop building elevated right-of-ways right through the urban fabric? There are a number of reasons, but perhaps the biggest is that they got timid about taking space from cars — whether permanently or temporarily during construction — and began to view putting rail lines down old freight rail right of ways or in tunnels or on the edge of dense areas as more politically expedient. But that choice has consequences and too often means rail line that can be less useful and more expensive when all is said and done.

It’s a problem that has become all too common for local transit agencies, beyond the aforementioned Sound Transit’s Everett Link stumbles. Refusal to take lanes is leading to problems on virtually every Sound Transit project and some in other regional transit agencies, as well.

- SR 522 Stride bus rapid transit is running into delays and pushback due to wiping out some trees and add a retaining wall to add new lanes instead of taking one of six existing road lanes.

- I-405 Stride bus rapid transit is delayed three years and overbudget due to new high capacity lanes and freeway interchanges.

- Pierce Transit’s Pacific Avenue bus rapid transit is delayed and in limbo after adding new lanes and because it became more expensive than initial estimates.

- Federal Way Link and Tacoma Dome Link Extension (TDLE) took an I-5 route to avoid taking lanes or disruptions to SR-99, but both extensions have run into complications and delays due to engineering challenges along I-5. TDLE planning is delayed three years to study a SR-99 alternative that was prematurely ruled out but may prove necessary.

- West Seattle Link’s arguably most promising station alternative in Alaska Junction was undercut by the refusal to take a Fauntleroy Way right-of-way leading to costly taking of some 300 new apartments along the road.

- Ballard Link is delayed and without a clear path forward due to the fear of losing car lanes on Westlake Avenue during construction. Former Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn, meanwhile, has proposed pedestrianizing Westlake Avenue permanently south of Denny Way to provide a marquee promenade, bike route, and linear park in Seattle.

- King County Metro bus routes like Route 8 and RapidRide E are mired in traffic congestion due to failure to provide and sufficently enforce dedicated bus lanes.

Repurposing car lanes isn’t an easy political lift, but it is one of the key missing ingredients to allow Seattle to build a world class rapid transit system and meet its climate goals. It’s hard to imagine the region building a metro system to rival Philadelphia’s without overcoming self-imposed obstacles.

But, once that hurdle is cleared, an incredible transformation is possible that creates high quality transit and urban spaces and helps wean us off of fossil fuels and avert climate catastrophe. It’s a bright future if we are not bound by the dictates of car dependency.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.