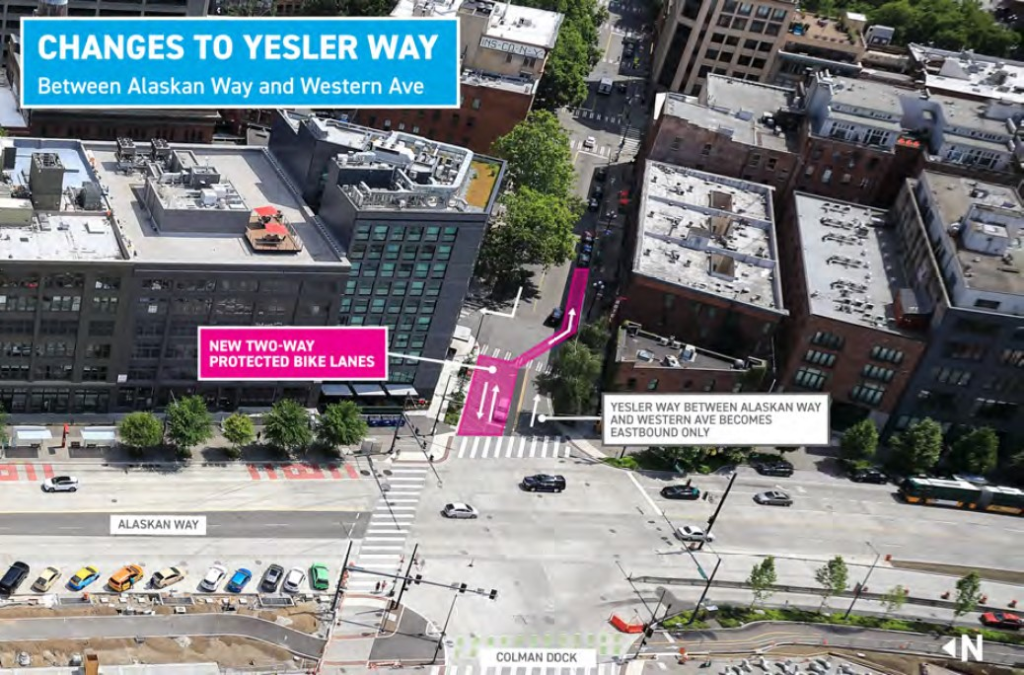

Early last week, crews with Seattle’s Office of the Waterfront installed a very short stretch of two-way bike lane, at the foot of Yesler Way approaching Alaskan Way and Washington State Ferries Colman Dock. The new bike lane was timed to go in at the same time that new traffic patterns around the state ferry terminal were being implemented: Drivers can no longer head west on Yesler past Western Avenue as part of this change.

But the brand new bike lane is less than 200 feet long, with street markings at Western Avenue sending eastbound bike riders across a diagonal at a four-way stop onto the other side of the street to head up the hill, and if they continue another three blocks they’ll need to cross back again to get into another two-way bike lane at Occidental Avenue S.

This significant gap illustrates a conspicuous truth about the overall Central Waterfront redevelopment: As work wraps up and the entire corridor is open to vehicle traffic, there is currently no timeline for a fully separated, protected bike lane to go in between the planned waterfront bike trail and the rest of Seattle’s downtown bike network. While the multiple arms of the waterfront project moved forward, decisions on how and where to make these connections were left to another time.

South End

Yesler Way is the most obvious place to make the connection between the Center City Bike Network and the waterfront: it’s fairly flat, and the gap is only a few blocks long right now. But as The Urbanist reported late last year, funding has not yet been identified to bridge that gap, despite an approximately $20 million project intended to strengthen the connections between streets in Pioneer Square and the Waterfront.

The big ticket item standing in the way of filling the funding gap is a new traffic signal at First Avenue and Yesler Way that SDOT says is required for a protected bike lane to be installed there. “We’d need a new traffic signal at Yesler Way & 1st Ave to allow a bike-only phase as well as creating a safer crossing at the diagonal intersection with James St. Building over areaways is complex too,” the department tweeted earlier this month in response to calls for filling the gap.

A follow-up tweet suggested that finding that funding is currently taking a backseat to finishing existing projects: “Though we’re always on the lookout for grant opportunities, we’re also working to finish strong on the #LevytoMoveSeattle & complete or nearly complete 7.5 miles of trail and protected bike lanes in SE Seattle by the end of 2024.”

The idea of connecting this gap didn’t come out of nowhere, however. Minutes from a July 2015 meeting of the Seattle bicycle advisory board, at which the Office of the Waterfront presented the most up-to-date plans for the waterfront bike path (at that time being called a cycletrack), detailed the city having the issue highlighted as designs were being finalized on the central waterfront corridor. “Important to look at [the] north end, how you transition from Elliot[t] and Western PBLs, as well as south-end connections at Yesler need to be considered for this project,” a recorded comment, unattributed to any individual board member, noted.

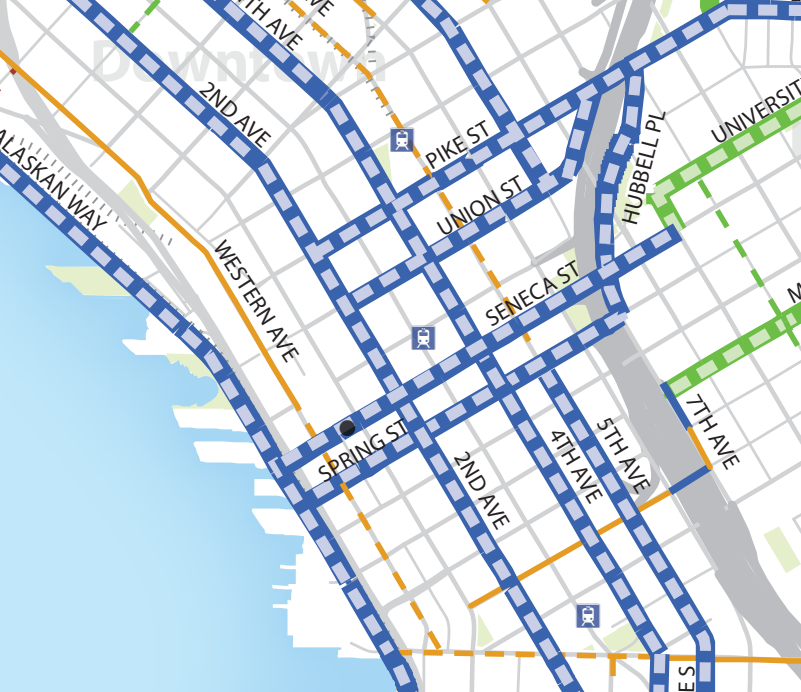

Central Downtown

The minutes from that 2015 meeting of the Bicycle Advisory Board also reveal that the presentation spent quite a bit of time dwelling on the issue of a connection between the waterfront bike trail to central downtown as well. Connections in this part of the city are more complicated than on Yesler Way, with some significant hills and streets that only connect as stairways.

“The key transitions (E-W connections) are being considered and will be designed (not yet decided if Spring and/or Seneca Street),” the 2015 notes from the Office of the Waterfront’s presentation read.

The 2014 Bicycle Master Plan, developed at nearly the same time that early decisions were being made on the Seattle waterfront project, calls for protected bike lanes on Spring and Seneca, presumably as one-way couplets given those streets are currently one-way. But Seneca doesn’t connect all the way through, with a wall where a former viaduct ramp once stood between First Avenue and Western Avenue, and a stairway presenting another obstacle.

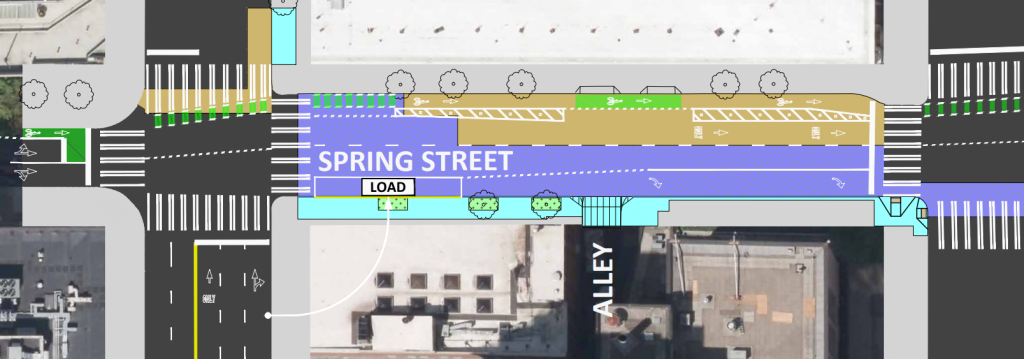

Spring Street, on the other hand, does connect through and while the block between First Avenue and Western Avenue is a little steep, it’s less steep than some of the nearby blocks, including further up Spring Street where bike facilities are planned. A two-way bike lane between Alaskan Way and Second Avenue would provide that direct connection to the waterfront bike trail, or if the city needed to get creative they could create the couplet with a connection to Seneca Street on Western Avenue.

The $130 million RapidRide G project will install a stretch of one-way protected bike lane on Spring Street connecting between First Avenue and Fourth Avenue, but nothing is planned west of First Avenue, which is considered outside the project scope.

Marion Street could provide another alternative to Spring Street: it’s even less steep than Spring west of First Avenue, but gets more steep between First and Second. A zig zag combination of the two wouldn’t be ideal, but it would create the connection. Right now, there is nothing on the horizon.

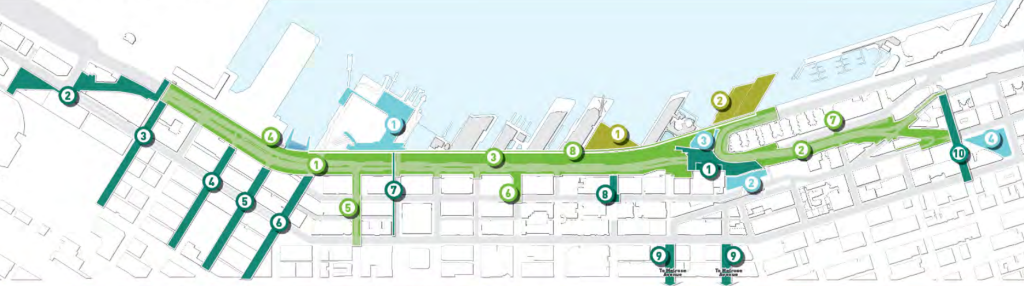

North End

The north end of the waterfront is where the most progress is happening with supplementary projects that will make the most of the waterfront path. The final connection between the aquarium and Myrtle Edwards Park is moving forward, following intense negotiations between SDOT, the Port of Seattle, and advocacy groups pushing for a design that makes the most sense along the corridor. SDOT is heading toward a mid-2024 date for construction on that final segment between Virginia Street and Broad Street, putting it on track to open not long after the initial stretch of bike path on the central waterfront opens next year.

But people biking who are looking to connect to the rest of the downtown bike network in Belltown are likely to end up frustrated for the foreseeable future. The brand new Elliott Way connector up to Belltown from Pike Place Market, open since this spring, will ultimately provide people on bikes a separated connection to Bell Street, even if the full northbound bike lane remains closed while work on the Overlook Walk continues. But at Bell Street anyone looking to continue further north finds a faded paint bike lane frequently blocked by parked cars.

The Bell Street project, one of the last waterfront projects to start design, currently includes a two-way protected bike lane on Bell Street that most people unfamiliar with the route will choose instead. That will connect just one additional block up to First Avenue: Beyond there, people on bikes will have to decide whether to continue against the direction of vehicle traffic on the curbless Bell Street between First and Fifth Avenues. Biking eastbound is technically allowed, but few people do it, given the fact that drivers on Bell, who are only supposed to be using the street for one block at a time, are all heading westbound, and are likely to come face-to-face with you head-on.

Like on the waterfront’s south end, and in the middle of downtown, a gap between planned bike facilities will remain unconnected, leaving the full potential of the investment in the waterfront untapped until the investment is prioritized. Further, if those gaps become priorities for future mayors or city councils they will almost certainly not be as seamless as they would be if it had all been planned at the same time in the way that vehicle access on the new waterfront was planned.

Given the fact that the Office of the Waterfront has been developing these plans as part of the $756 million waterfront project for over a decade, the unfilled gaps speak to the way that providing bike access through the coming multiuse path and bike lanes on Elliott Way has been lip service. The fact that no novice bike rider will be able to connect between these new facilities and the rest of downtown without mixing with traffic speaks for itself.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.