A plan to dramatically expand Seattle’s school zone speed enforcement program hit a snag this week.

The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) told a city council committee that new cameras likely wouldn’t be able to be in place until well after the start of the 2024-2025 school year. That had been the deadline laid out by a budget amendment passed last fall, spearheaded by Councilmember Alex Pedersen, who has been cheerleading for an expansion of automatic speed enforcement from his role as transportation committee chair.

Currently, only around 20% of the city’s public schools have an automatic speed camera that enforces a speed limit of 20 mph during the times immediately before and after school on the nearest arterial street.

Representatives from SDOT cited a 14-month lead time for design and construction of the new cameras and an anticipated need for more funding and staff capacity at three city departments as the primary reasons that turning on cameras at as many as 19 new locations in the city by the start of the 2024 school year is infeasible. An October 2024 completion date is a “best case scenario,” the agency said. Under the budget amendment, SDOT was not actually provided any funding to expand the camera program this year, with 2023 funding instead allocated to the Seattle Police Department (SPD), which reviews camera footage and issues citations.

“There is very significant risk of delays to various steps with this particular schedule, and it’d be highly unlikely, even if we started today, that we could actually get this expansion done by the start of the next school year,” Seattle’s City Traffic Engineer, Venu Nemani, told the council’s transportation committee Tuesday.

The long timeline for implementation raises questions about how soon Seattle might be able to move forward with implementing newly authorized types of speed cameras, including those enforcing “street racing zones” and speeds outside parks, hospitals, and directly along routes where kids walk to school. Unlike the school zone cameras, which are only activated for less than two hours every day and only on days when school is in session, those new types of cameras, which the state legislature authorized in 2022, can be operated 24/7 and could prove to be even more effective.

SPD Staffing Could Hinder Camera Expansion Plan

Along with the strong risk of delays to camera expansion on SDOT’s side via design and construction, staffing at the Seattle Police Department will also likely present clear constraints on the city’s ability to expand the program. Despite recent hiring incentives approved by the city council, the number of sworn officers at SPD is not increasing and remains well below the numbers called for in the department’s hiring plan. But under the city’s interpretation of state law, only sworn officers are able to review footage and issue citations, a task generally assigned to officers on desk duty.

During Tuesday’s meeting, a recent incident in which hundreds of automatic camera citations within the Seattle Police Department’s backlog lapsed because they could not be mailed to drivers quickly enough came up. The incident, which led to a $6.5 million shortfall in SDOT’s pedestrian safety and Safe Routes to Schools budget, is said to have been resolved by SPD by implementing a new staffing plan for camera citation duty. But with a planned doubling of cameras, it’s not clear that the staffing is there to keep up. Overall, once the new cameras are in place, the entire program is expected to cost an additional $2.5 million per year, a number that is expected to be offset from revenue generated from citations.

With the significant expansion of speed camera authority at the state level, there will likely come a push to modify current state law around who can review footage. Seattle’s School Traffic Safety Committee is one body asking the state legislature to consider expanding that authority to public employees more broadly.

“[The committee] asks state legislators to pass a law allowing review of automated traffic enforcement citations by any trained and capable individual, including local transportation department staff,” their 2023 annual report noted. At Tuesday’s meeting, Councilmember Lisa Herbold was also interested in exploring the issue with state legislators via the city’s Office of Intergovernmental Relations.

New School Zone Cameras Would Be Concentrated in More Affluent Areas

Under the expansion plan presented this week, SDOT would add cameras to 19 schools across the city, focusing on schools where driver speeds are highest, and where adding flashing rapid beacons to school-adjacent crossings haven’t been effective. From there, the department applied an equity lens, based on the recommendations of SDOT’s Transportation Equity Workgroup to ensure that speed cameras are equally distributed around the city.

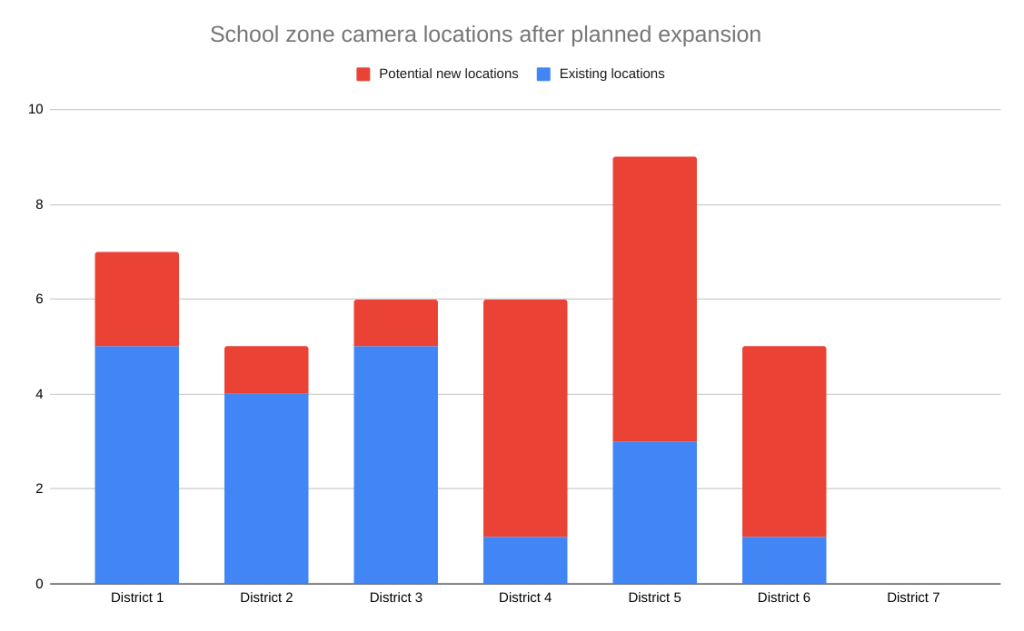

Currently, a significant majority of existing speed cameras are located south of the ship canal, with the highest number in Districts 1 (West Seattle) and 3 (Central-east Seattle), followed by District 2 (Southeast Seattle). Under the plan, the “most disadvantaged” neighborhoods in the city would be intentionally excluded as locations for new cameras, with other speed reduction treatments prioritized near those schools instead.

The city’s northernmost District 5 would see the most new locations under the plan, with six schools added, followed by Northeast Seattle’s District 4 with five schools and Northwest Seattle’s District 6 with four new camera locations. South Seattle’s District 2, where 44% of the fatal and serious crashes between 2019-2021 occurred, would only see one new camera location under the plan. District 7, which includes Queen Anne and parts of Magnolia as well as most downtown neighborhoods, would continue as the only council district without any school zone speed cameras even under the expansion plan.

Nemani told the committee that recommendations from SDOT’s Transportation Equity Workgroup to distribute cameras equally around the city informed the plan, but that the department would look more to street design in places like South Seattle to improve safety outside schools.

“In those locations with the highest disadvantage, we are leaning in on more of the engineering treatments: curb bulbs, speed cushions, radar feedback signs, and the like to reduce speeding and improve safety,” Nemani said.

Much of the conversation Tuesday centered around the idea of whether distributing cameras more equally around the city would lead to more equitable outcomes.

“I think it’s important to be very clear: When we say equitable in the city, we do not mean equal, particularly when we’re talking about issues of communities of color who have been disadvantaged by past policies and practices,” District 2 Councilmember Tammy Morales said. “Equitable means those communities get more, so they come up to a level that the rest of the city benefits from.”

But Morales wasn’t advocating that more cameras be added in her district.

“I think it’s important to acknowledge that if we’re really going to create safety for pedestrians… we do need to shift our focus to engineering, and road diets, and rethinking how we design the streets so that it is not easy for people to speed and run lights and take corners that put people in jeopardy.”

Morales once again expressed frustration at the slow deployment of such safety treatments in her district, but stopped short of directly advocating for cameras to make up the difference.

District 1 Councilmember Lisa Herbold was even more openly critical of SDOT’s camera deployment plan, voicing concerns that the department was ignoring people who might benefit from the installation of cameras in underserved areas.

“I’m concerned we’re only looking at this question from one perspective,” Herbold said. “We can’t just be talking to people who are advocating for reduced financial obligations of people living in these neighborhoods… we must also be talking to people whose safety is negatively impacted.”

But no councilmember Tuesday suggested going so far as to direct SDOT in a different direction than the plan they laid out. And there was a broad agreement that camera enforcement should be moving forward.

Alex Pedersen, the council’s most outspoken advocate for new cameras, suggested that the department should be working to streamline how they roll out future cameras.

“I think SDOT is going to have to figure out how to embrace and scale this up,” Pedersen said, noting that even after the number of cameras is doubled, fewer than half of the public schools in the city will have speed cameras adjacent to them. “This is not to replace transportation safety infrastructure improvements,” he said. “We need to do both, and we need to do it where we’re seeing the most fatalities and serious injuries.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.