Starved of vehicles and storage space, the full light rail expansion program is threatened with reduced service levels and quality. Another major reset is now in order to deliver the voter-approved Sound Transit 3 program.

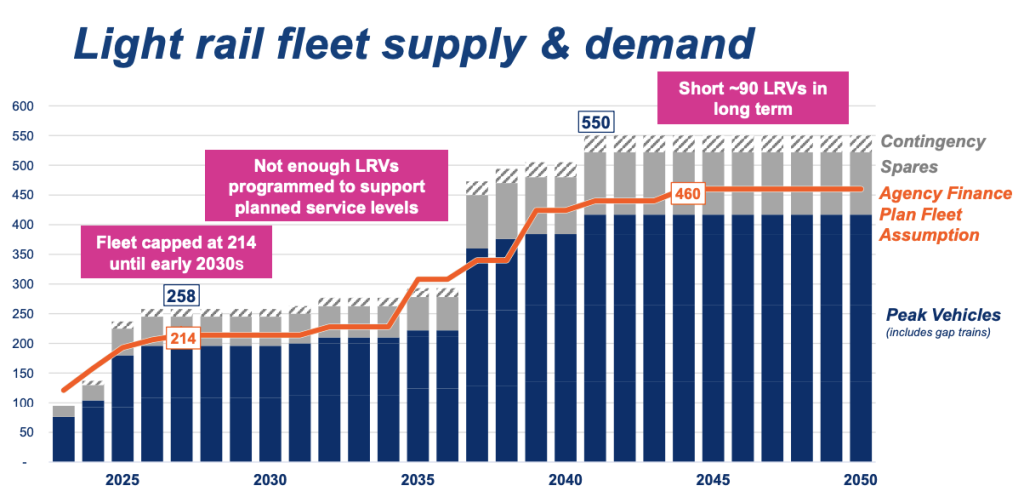

Sound Transit service planners have detailed Link fleet constraints over the next 30 years, and their models show that the Link light rail system is slated to be gravely short of the requisite number of vehicles and vehicle storage spaces to reliably operate the full system by the early 2040s, but shortages are projected to be an issue even in the short- and mid-term.

Even now, riders are seeing the impacts of vehicle shortages. The rate of shorter trains has been increasing in recent months as individual light rail vehicles (LRVs) go out of service for maintenance and repair. That hasn’t necessarily meant fewer trips being operated, but many trips have been running with three-car rather than four-car trains, which can exacerbate crowding issues. Shorter trains is one way to address vehicle shortages, but Sound Transit may face more draconian service choices as time moves forward.

Baked into new forecasted fleet and capacity need assessments are a lot of assumptions. Those include things like anticipated service levels, fleet expansion and replacement rates, and storage and maintenance capacity, as well as real-world runtimes, spare ratio and fleet contingency needs, and right-sizing service to rider demand.

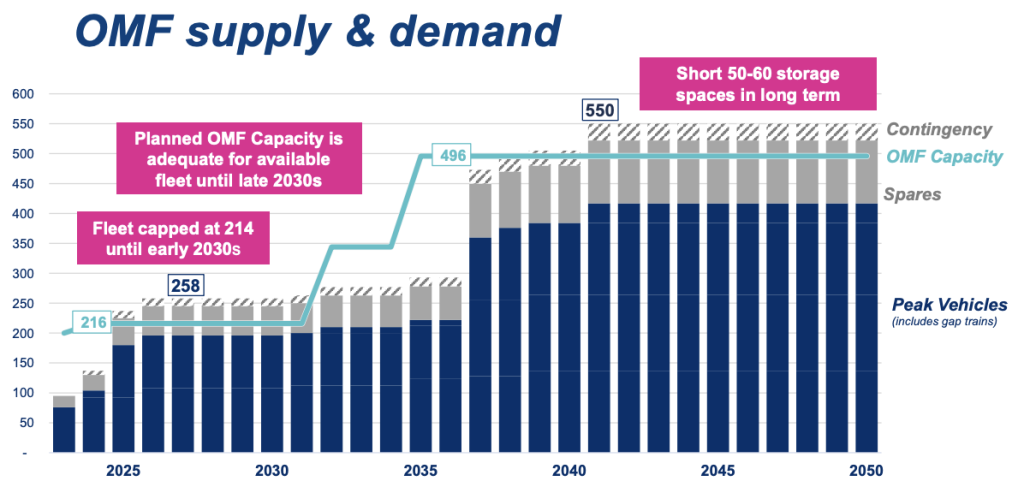

Underpinning the forecasts, planners are assuming that all Link lines will have six-minute peak-hour frequencies by the 2040s and that fleet will progressively grow to a total of 460 LRVs. Operations and maintenance facility (OMF) capacity is also planned to reach to 496 LRV spaces by the mid-2030s.

In June, service planner Matt Sheldon briefed Sound Transit boardmembers on the latest modeled scenarios and the news wasn’t good.

“The bottomline is we are now forecasting that we will need approximately 90 or more vehicles than we currently have programmed to provide that six-minute rush-hour service on all lines by the time we’ve built out the ST3 program,” Sheldon said.

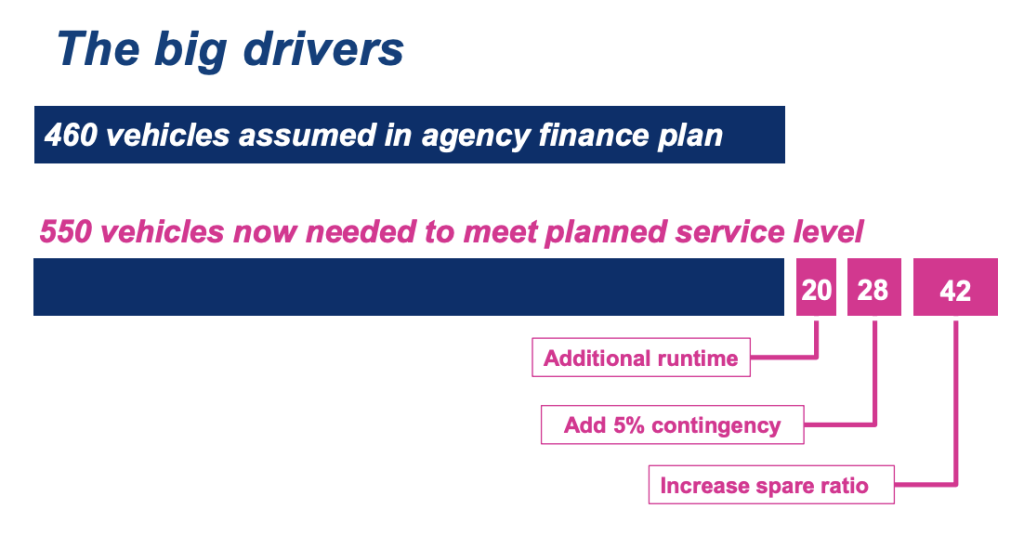

Part of the problem lies in the fact that Sound Transit has had to face the reality of operating a complex system in the real-world rather than on paper. “We’re finding that we need to add more running time into our system to account for slower than planned operations in some areas, such as at grade sections in the Rainier Valley and SoDo and in some tunneled areas where we have tight curves,” Sheldon said. “We’re also having to do more daily maintenance on our rail cars, which is taking more cars out of service more often. This is known as our spare ratio and we believe it needs to increase as the system expands.”

In allocating the 90 or so additional LRVs needed, Sheldon said that 20 are needed for additional runtime, 42 are needed for spares, and 28 are needed as a contingency. The problem, however, is that the agency hasn’t budgeted for these additional vehicle needs or the space to store and maintain them under the finance plan.

Data shared by Sheldon also clearly illustrated that short- and mid-term expansions are going to be heavily constrained. Even in this decade, LRV fleet availability is forecasted to be short of the number required to reliably operate service and normal storage capacity won’t be enough. That problem continues into the 2030s and generally worsens over time.

“In the near-term through build out of our ST2 extensions this decade, we will have 214 vehicles available,” Sheldon said. “We now forecast even closer to 260 vehicles needed to support planned service, but we don’t have much flexibility in this period since we won’t have additional vehicles until the early 2030s.”

As a result of insufficient capacity, Sheldon said that the agency may “need to look at modifying planned service levels to better match the fleet we will have.” That could mean reducing frequencies, running shorter trains, operating some trips on a shorter portion of a line or reconfiguring lines, or some mix of those strategies and possibly others.

To solve these problems long-term, Sheldon told boardmembers that a blunt strategy could be to purchase more LRVs. But that would also require increasing the size of OMFs or building additional ones to accommodate trains. OMF and vehicle costs haven’t been coming in cheap lately and likely would reach over $4 billion for the level of investment needed. Sheldon suggested that other possible options could involve addressing at-grade segments and existing infrastructure problems as well as altering planned service levels.

Claudia Balducci, a boardmember and chair of the System Expansion Committee, had several things to say in response to the briefing.

“I’m feeling and hearing a real interest in understanding better the problem statement with some contextual data, maybe some benchmarking data would be really good data to have,” she said. For her, slide deck presentations aren’t delivering the level of detail needed to fully understand the issues and policy choices that the agency is facing.

Balducci also expressed an interest in creating “more reliable operating environments on the system.” That could wind up being enhancements or replacement of existing infrastructure deficiencies, but Balducci took the opportunity to push back on some staff assumptions on system design.

“I keep hearing side comments in a variety of different presentations about our operating environment and the potential need for more maintenance capacity in different locations in order to keep the system going,” Balducci said. “And I have to say that the potential for needing more OMF capacity in different locations was a key reason given when the staff said we couldn’t possibly rethink how we structure service in the tunnels.”

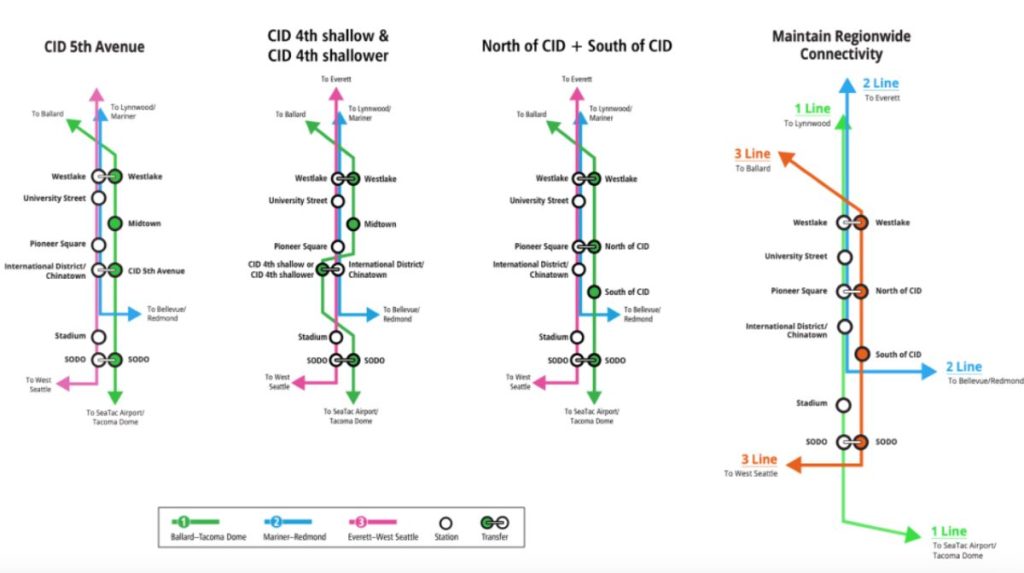

In March, before the full agency board voted to approve a motion reseting the Ballard Link Extension environmental review process, Balducci offered an amendment that would have required study of an alternative Link operating system plan. That alternative was proposed as a means to maintain regional connectivity by coupling the West Seattle and Ballard Link Extensions into a single line via the new downtown tunnel and operating the 1 and 2 Lines via the existing downtown tunnel. In an effort to dismiss the idea, board chair King County Executive Dow Constantine called on staff with Don Billen, a chief project development planner, laying out outdated assumptions and arguments against the study.

Nevertheless, a rethink could still be in order. A standalone West Seattle and Ballard Link line, for instance, could have a lot of upsides. That could open up the possibility of it being constructed as an automated light metro system — like SkyTrain in Vancouver — with much smaller station footprints, shorter trainsets, and a much smaller OMF. That type of line could also be operated at much higher service levels virtually for free and it wouldn’t be subject to the problems Link faces now with at-grade segments, long operating lengths, and operator variability. All in all, project costs for the line could come down substantially and potentially make up the difference for the other parts of the Link system being built out as light rail — parts of the system that almost assuredly aren’t going to get delivered under the “affordable schedules” if larger or additional light rail OMFs with more LRVs are necessitated.

Whether or not a single West Seattle and Ballard Link line may finally get a fair shake by staff as part of this process remains to be seen. But Balducci did set an optimistic tone about the broader service planning process.

“It sounds like we’re rethinking how we structure service and our OMFs,” she said. “So I just want to be very clear that…we should maintain an open mind about our service structures that can be used to serve our riders better in addition to making the system work better.”

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.