A committee nod smooths the path for camera expansion, but some advocates worry about the equity implications.

Seattle’s streets are set to see a significant increase in the number of automatic speed cameras over the coming year, as policymakers look for new avenues that could help to reverse the worrying trend line of traffic deaths and serious injuries across the city in recent years. With drivers exceeding posted speed limits increasingly the norm on arterial roads, cameras could be a way to bring those speeds back down without turning to in-person police enforcement. But even as the consensus grows that cameras should play a role, there’s a lot of disagreement on just how large that role should be.

This week, the Seattle city council’s transportation committee gave the greenlight to a bill that will give Seattle’s mayor broad authority to expand the use of automatic speed cameras on the city’s streets beyond what’s currently allowed: for red-light running, in school zones, and as part of a small “block the box” and bus lane enforcement pilot. A provision allowing cameras along designated “speed racing zones” is taking center stage, but the bill sets up the city to be able to deploy cameras in a broad number of other instances, including locations near parks, hospitals, routes where kids walk to school, and at intersections that have a significant history of crashes.

The new authority represents an alliance between councilmembers, including transportation chair Alex Pedersen, who sees camera enforcement as a necessary supplement to aid law enforcement, as police departments across the country struggle to meet hiring goals, and Councilmember Tammy Morales, who has stated a preference for automated enforcement over biased policing and as a step forward for those who are tired of waiting for long-promised infrastructure investments to do the job of making streets safer.

“The truth is, the only mechanism being afforded to us, especially for folks in the South End, in order to keep us safe while using public infrastructure, is something like traffic enforcement,” Morales said ahead of Tuesday’s vote, lamenting delays to a number of street safety projects in her district, including on MLK Jr Way S, 15th Avenue S, and Lake Washington Boulevard.

“I don’t understand why over and over again the department chooses to delay safety projects in places where people are dying, where collision frequency can be used to set a watch,” Morales said. “I think SDOT’s own engineers would tell you that relying on enforcement for traffic safety is antiquated. We really need to be looking, as I’ve said before, at our street design.”

Camera enforcement could provide the city with a progressive source of revenue to be reinvested back into those physical improvements that change the design of roadways, but right now the nexus between camera revenue and what the funds are used for is opaque. And some advocates are pushing for a more thoughtful conversation before adding many more cameras.

Seattle is not the first city to move to take advantage of the new camera authority under state law, with Tukwila moving to implement speed cameras at a dangerous spot outside a public park late last year. But many of the state’s largest cities, where the potential for safety gains would be greatest, have been mostly slow to react to being handed the new authority.

Seattle Already Set to Double School Zone Cameras

Last year, the Seattle City Council approved a budget amendment proposed by transportation committee chair Alex Pedersen that had the aim of doubling the number of automatic speed cameras immediately adjacent to schools in the city, from 35 to 70. With that amendment, the council also put in place a stipulation that those cameras couldn’t be expanded until a report, outlining the steps the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) was taking to ensure that the expansion happened in an equitable way. That report is due this August, extended from a deadline this month. The council also requested that SDOT provide recommendations on how to potentially expand automatic traffic cameras in the future.

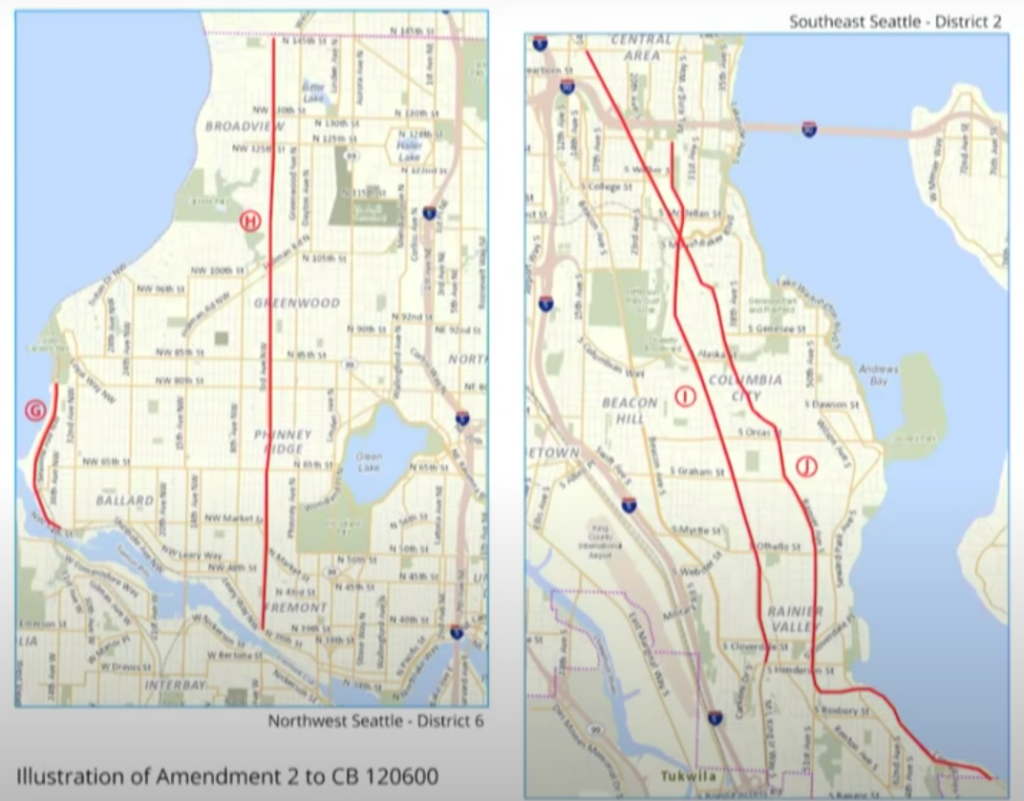

After the passage of this new bill in the coming weeks, the City of Seattle will be able to add cameras everywhere that they’re allowed by state law. The provision around street racing zones, brought forward by Councilmember Lisa Herbold in response to complaints about unsafe street racing along Harbor Avenue SW and Alki Avenue SW in District 1, requires specific streets be designated directly in the law. Along with those streets, the proposal advanced out of committee includes West Marginal Way SW, Sand Point Way NE, streets inside Magnuson Park, Seaview Avenue NW, and a few other corridors notorious for high speeds. It also includes, thanks to an amendment by Councilmember Morales, the entirety of Rainier Avenue and all of MLK Jr Way S within District 2.

In putting forward the amendment, Morales noted that those two high-speed corridors saw 150 more collisions in 2022 than the rest of the other streets set to be designated as racing zones combined. But the city wouldn’t necessarily have to designate a street a racing zone to be able to add cameras to control speeds, with many of the city’s most dangerous streets passing by parks and hospitals.

Advocates Urging More Thoughtfulness Around Equity

Whose Streets, Our Streets, a project within Seattle Neighborhood Greenways made up of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) transportation advocates pushing for more equitable transportation policies, recently issued a set of recommendations after conducting community outreach around the issue of automated camera enforcement earlier this year. Broadly, the recommendations push for impacts on lower-income Seattle residents to be considered, the geographic distribution of cameras throughout city to be more equal, and to make clear how information generated by the cameras can or cannot be used elsewhere in government. They also ask for the City to develop a policy of how physical changes to roads will be made thanks to the funds generated by speed cameras.

“There’s that common perception that we can use automated enforcement cameras as a replacement for traffic stops…so it’s sort of shifting the way that we enforce. And there’s no reason to expect that it would be really a replacement,” Ethan C. Campbell, a researcher who organizes with Whose Streets Our Streets, told The Urbanist. “And we’re talking about now, with doubling the [school zone] speed cameras, potentially another 100,000, maybe 200,000 tickets every year. It’s a really, really big expansion of this mode of enforcement that as a city, I think we really haven’t had a conversation about whether this is the future that we want.”

“Automated cameras, we believe, can help, but they aren’t the most effective solution,” Whose Streets, Our Streets’ Nura Ahmed said, echoing Morales’s call for the city to focus on the design of roads. “The most effective way to make cars go slower is designing streets for slower speeds.”

Councilmember Alex Pedersen Pushing Cameras Behind the Scenes

In advance of the committee vote this week, transportation committee chair Alex Pedersen has been an outspoken advocate of advancing more automatic cameras across the city. He has promoted that view to constituents, in places like his email newsletter, but also directly to city leadership as the Harrell administration seeks to implement a broader roadway safety strategy.

After the release of the “Top to Bottom” review of Seattle’s Vision Zero report earlier this year, Deputy Mayor Adiam Emery, who was then-executive general manager in Mayor Bruce Harrell’s office, wrote to Pedersen informing him that one of the first “momentum building” actions moving forward would be “starting a conversation” about more automated traffic enforcement. But Pedersen didn’t think the answer was more process.

“Personally, I don’t think we need more conversations about automated enforcement – I believe it’s overdue already,” Pedersen replied to Emery in February. “When I toured District 2 with Councilmenber Morales last year, we read letters from students imploring us to better enforce speeding laws.”

Pedersen noted that the Seattle Municipal Court already has a program in place that assists lower-income drivers who can’t afford to pay their tickets immediately. He continued that support for the idea across other departments. In March, Pedersen sent an email to Seattle Police Chief Adrian Diaz, reemphasizing his support for expanding automatic cameras, citing the department’s shortage of officers.

“I concur with SDOT Director Greg Spotts that we should view this not as more tasks to perform, but rather as an additional authorized tool to deliver improved public safety efficiently with our currently limited personnel,” Pedersen wrote. “That staffing shortage of officers in the field is another reason, I believe, to fully embrace expanded automated camera enforcement to achieve similar outcomes, because officers who might not be able to participate in field duty could be the ones to confirm the traffic tickets that would be issued with the expanded automated enforcement.”

Pedersen also spoke to the need to scale tickets to the income level of the driver, an idea that would gain support for camera expansion with groups like Whose Streets, Our Streets, but that idea has not yet made it into any legislation that the council has considered so far.

With a number of steps still to happen before new cameras actually hit the streets, it remains to be seen just exactly how the council will respond to calls to ensure cameras don’t disproportionately impact low income Seattle residents.

Camera Enforcement Getting Statewide Attention

Outside Seattle, transportation officials are also looking at the potential automatic cameras have to reverse Washington’s terrible trend line when it comes to traffic violence. Last month, as part of a panel discussion looking at the performance of state initiatives to reduce fatal and serious traffic collisions statewide, Governor Jay Inslee prodded members of his administration, including the director of the Washington Traffic Safety Commission, to take a broader look at how to implement automatic speed cameras on state highways.

This session, the state legislature — which otherwise punted on traffic safety — gave the go-ahead for the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) to install speed cameras in active highway work zones, but the highway department isn’t currently authorized to use them to enforce speeding more broadly.

“We have a law, we’re not supposed to drive over a certain speed. Why should we not do that, given the carnage that we’re seeing on our highways right now?” Inslee said at the event.

“I have a hard time understanding why we’re not saturated with traffic cameras,” Shelly Baldwin, the director of the traffic safety commission, told the Governor. The commission’s role primarily revolves around administering federal safety grants to state and local agencies, many of which are required by law to be spent on police enforcement or education campaigns, not physical infrastructure. But the body also makes recommendations to the state legislature, with their opinion given significant weight.

Given the high proportion of fatal and serious injuries in Washington that occur on state highways, automatically enforced speed management could have a big impact. But with many state highways also functioning as a city’s main street, the idea of the state imposing the idea of cameras on localities could meet significant pushback.

It’s clear that the statewide conversation around use of cameras will likely only intensify, but less clear whether state and local leaders will actually be able to push through the tough conversations to save the most lives.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.