In rejecting midrise zoning, Councilmember Robertson cited a handshake agreement with homeowners, worrying more homes would “unduly alarm the neighborhoods.”

If completing legally-mandated, once-in-a-decade planning work were a race, Bellevue would be on its way to winning. Where other cities are seeing unplanned delays to their Comprehensive Plan Periodic Updates, the Eastside city of 150,000 residents is slated to advance its preferred alternative for further environmental study in just a matter of weeks. This sets the stage for land use decisions that will guide Bellevue’s growth for the next 20 years — impacting everything from housing affordability to transportation options to environmental stewardship and more.

As early as this Monday, Bellevue City Council will be discussing what land use alternative to advance to later rounds of study in the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) process. But one Councilmember has already played her part to advocate against more growth before Council’s wider discussion — an apparent breach of city protocols.

Less Capacity Equals Less Housing Development

At a June 28th meeting of Bellevue’s Planning Commission, Councilmember Jennifer Robertson admitted that she unilaterally directed staff to reduce proposed zoning in neighborhood commercial centers down from what was originally proposed to the commission. Citing “an agreement with the neighborhoods” to place growth exclusively in the growth centers, Robertson expressed “alarm” at an original staff proposal to allow up to seven- to ten-story buildings in select commercial areas. Setting zoning capacity so high in the preferred alternative would “set expectations of property owners” and “unduly alarm the neighborhoods,” Robertson said.

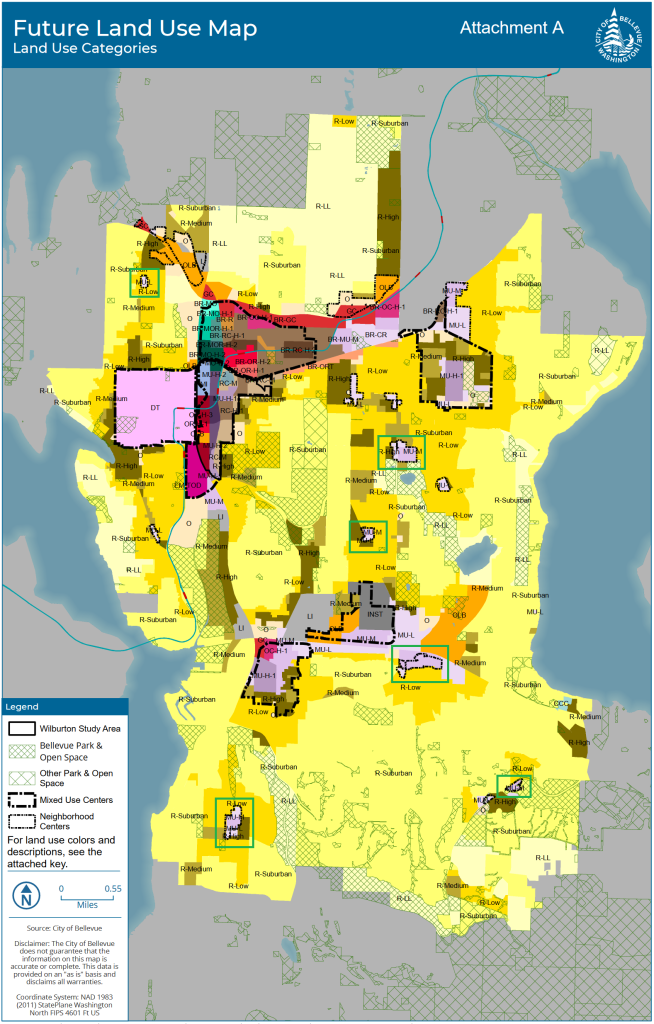

Currently, these areas are often zoned for “Neighborhood Business,” which allows for a mix of small-scale commercial and residential uses stories. All alternatives studied in the city’s Draft EIS evaluated these parcels effectively remaining at this zoning level through a new Mixed Use – Lowrise (MU-L) designation, which would accommodate buildings between two and four stories.

However, in response to multiple comments from developers and neighborhood center parcel owners who said housing redevelopments would not be possible without allowances for further density, staff proposed advancing the higher zoning category of Mixed Use – Midrise (MU-M) in the preferred alternative. Across all the neighborhood center sites in Bellevue proposed by staff, the higher zoning classification could create capacity for thousands of additional housing units.

Robertson’s objections to the midrise classification prompted staff to return to the commission to reexamine the zoning in Neighborhood Centers and have them decide between MU-L or a new, undefined “MU Low-Mid” compromise that would fall between the two designations. The vote came immediately after Robertson’s strong comments against density and ultimately went 3-2 in support of retaining the lowrise zoning (MU-L) in the preferred alternative.

When speaking against the proposed midrise zoning, Robertson characterized commenters supporting higher capacity as “one or two property owners that want to increase density” and their profits, but this critique overlooks the reality that limited zoning capacity means less housing will get built in a city with some of the most expensive housing costs in the county. Citywide, more than 70% of residential land is under restrictive single family zoning, and unlike neighboring cities like Kirkland and Seattle, Bellevue has yet to pass detached accessory dwelling unit reform, which would enable backyard cottages on single family lots.

In their Draft EIS comments, Aegis Senior Living, the owners of a Lake Hills parcel within the BelEast Neighborhood Center, said today’s lowrise zoning has left residential developers uninterested in their land because of limited economic feasibility — an outcome that would likely continue if the restrictions of current zoning are carried over into the MU-L designation. The property — next to two frequent transit lines that connect with Issaquah, Downtown Bellevue, Kirkland, and the University of Washington’s Seattle campus — remains vacant.

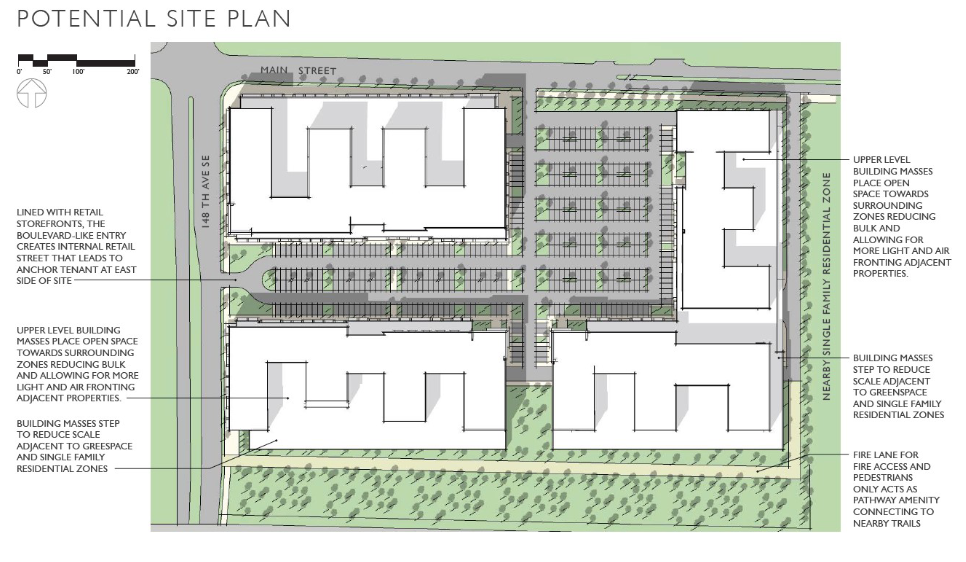

The Kelsey Creek Center, a neighborhood center located along the frequent King County Metro Route 245 and 148th Ave SE, is similarly devoid of housing. But opportunities to add residential development could be limited without an expansion of housing capacity on the site. “The Mixed-Use Lowrise densities and application of the Transition Area standards is unlikely to support sufficient capacity and flexibility to allow viable redevelopment,” wrote the developer in their EIS comments.

And although some developers of Neighborhood Center parcels acknowledge that MU-L zoning could allow for profitable townhome development on their particular parcels, many of the centers’ proximity to frequent transit raises the question if such zoning is the most effective use of space. For example, Northtowne Shopping Center in the neighborhood of Northwest Bellevue is along the future Route 270, which will run with 10 minute headways between Seattle’s University District and Downtown Bellevue once East Link light rail opens and transit agencies restructure their bus routes to accommodate added service. Furthermore, the site is just a half-mile away from SR 520 and its associated bike path, which enables further opportunities for multimodal travel.

Unfortunately, these poor policy outcomes compose just one aspect of this questionable decision. A councilmember directly interfering with a commission’s business to affect their policy recommendation appears to represent a violation of agreed-upon Council rules.

A Breach of City Procedure

In accordance with Bellevue City Code Chapter 3.64, the seven-member Bellevue Planning Commission acts as a policy advisory body to the City Council on matters of land use and the Comprehensive Plan. In practice, City Council initiates a body of land use planning work that is sent to the Planning Commission for deliberation and analysis. After a series of meetings and public outreach, the commission returns to the entire Council with a policy recommendation to be then approved, amended, or rejected by the City Council.

Councilmember Robertson serves as the commission’s Council liaison, meaning she attends commission meetings, provides the body with “big picture perspectives,” and keeps Council apprised of the body’s work. According to rules originally established in 2015 however, individual councilmembers are not allowed to provide direction to any commission that does not reflect the perspective of the full Council. When Council guidance is needed to supplement a commission’s decision-making, the Council liaison is supposed to return to the full body to obtain that recommendation. Furthermore, guidance from those 2015 rules advises Councilmembers to be accepting of commission decisions that do not match with stated Council policy.

Therefore, Councilmember Robertson’s actions do not just represent a poor policy choice that reduces Bellevue’s capacity for housing by thousands of units. They run contrary to long-standing Council rules and procedures that clearly define a division of labor between the city’s boards, commissions, and Council. Councilmembers are allowed to amend or reject policies once they have been recommended by a commission (and indeed Councilmember Robertson has). However, these rules establish that individual councilmembers are not to interfere in the minutiae of commission business.

Although Robertson argued that keeping density away from single-family neighborhoods has been a “pact” maintained by the whole Council, she also repeatedly stated that her comments against midrise zoning represented her own personal opinion. No policy to restrict growth exclusively to certain neighborhoods has been formally established as part of the 2021-23 Council Priorities. However, the policy has been a key issue of Councilmember Robertson’s campaign platform across her 14 years in office.

Robertson is unlikely to face disciplinary consequences for her meddling, as Council rules do not outline a procedure for violations of this nature. Furthermore, she will not face electoral consequences because she has announced she will be leaving City Council in December at the end of her term. However, her unilateral action to limit growth in Bellevue could have long-standing impacts if left unchallenged. By limiting housing access in neighborhoods that have historically been exempted from growth, her influence has furthered a paradigm that has left high-opportunity areas of Bellevue only accessible to the very wealthy.

The full City Council will still have an opportunity to weigh in on the preferred alternative over the coming weeks, so it is still possible that further amendments could be made, including rezoning neighborhood centers back up to the originally proposed midrise designation. Across the three growth alternatives studied during this Comp Plan update, Alternative 3 (the option with the most capacity for growth) has been the one to receive the most support from advocates, developers, businesses, residents, and organizations alike.

Alternative 3 called for growth in the city’s larger mixed use neighborhoods (Crossroads, Factoria, and Eastgate), housing in the neighborhood centers, and modest growth around the neighborhood centers. If what City Council passes does not create sufficient capacity to actually allow for housing growth in neighborhood centers, then they will not be recognizing Bellevue’s urgent need for more housing and the diverse stakeholders who support Alternative 3.

If you live in Bellevue and want to see more housing in your community, email council@bellevuewa.gov with your name and neighborhood. Explain why having more housing options in your city is important to you, and ask for midrise development to be allowed in neighborhood commercial centers. Your comments help Council understand that residents are not inherently opposed to housing growth.

Chris Randels is the founder and director of Complete Streets Bellevue, an advocacy organization looking to make it easier for people to get around Bellevue without a car. Chris lived in the Lake Hills neighborhood for nearly a decade and cares about reducing emissions and improving safety in the Eastside's largest city.