Commerce recently had a consultant create a form-based code, but the draft fails to advance housing abundance.

Now that Washington State’s Middle Housing bill (HB1110) has been signed into law, the next question is what implementation will look like — what kind of housing and where. The Department of Commerce has published a request for consultants to draft a model code that 1) will help jurisdictions write their own compliant middle housing code or 2) will supersede local zoning if they fail to implement their own in advance of the deadline (six months after their comprehensive planning update).

While we don’t know what cities and towns are thinking, we do have a picture of how Commerce is approaching the middle housing code. Last fall, Commerce hired a consultant to “inform about and assist local governments with middle housing policies, regulations, and programs.”

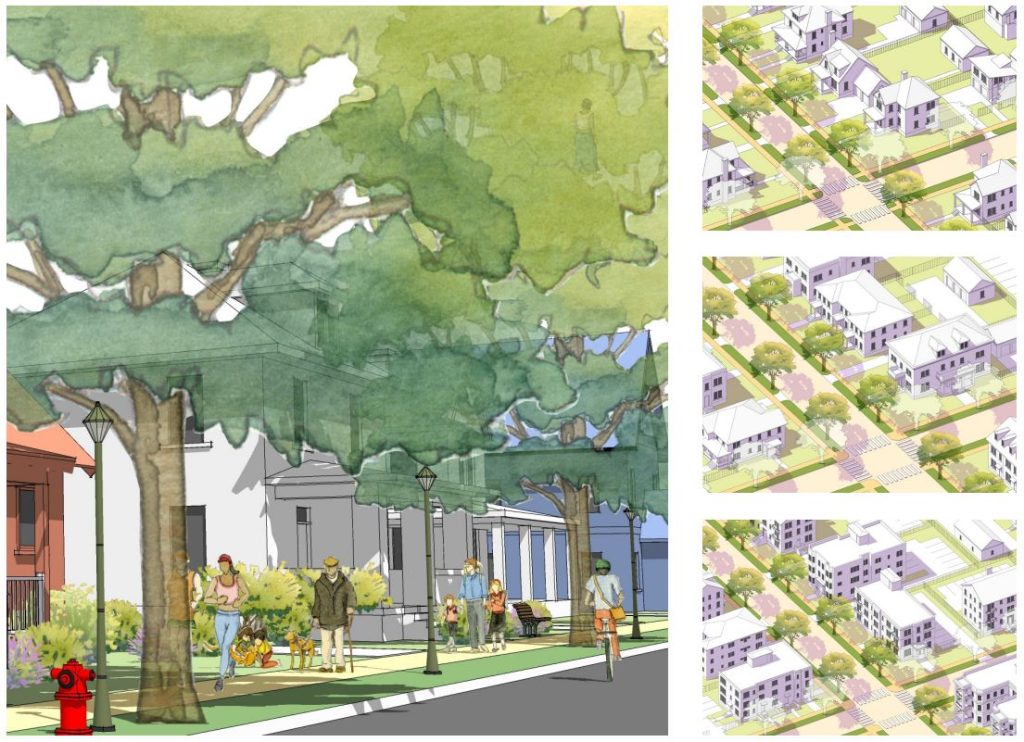

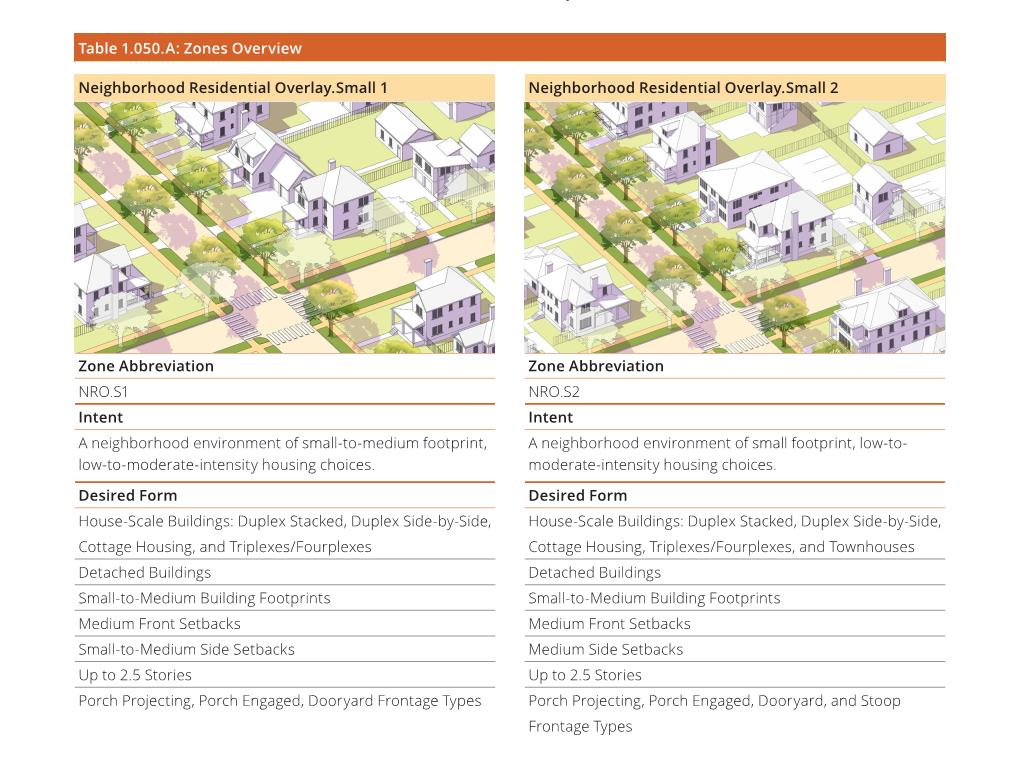

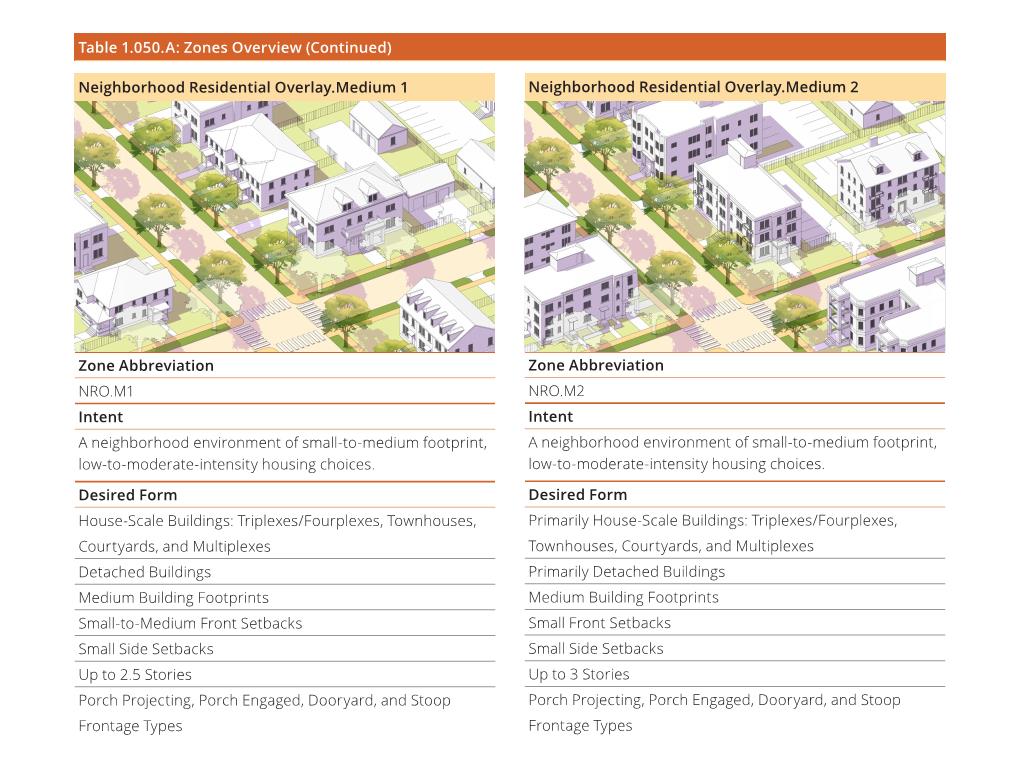

In May, a focus group of planners, developers, and architects previewed a draft ‘Toolkit’ that illustrates four strategies that local governments could overlay on their residential zoning to allow new denser housing types within existing detached single family neighborhoods. The foundation of this toolkit is a form-based code meant to create ‘objective’ standards for middle housing that can be applied widely.

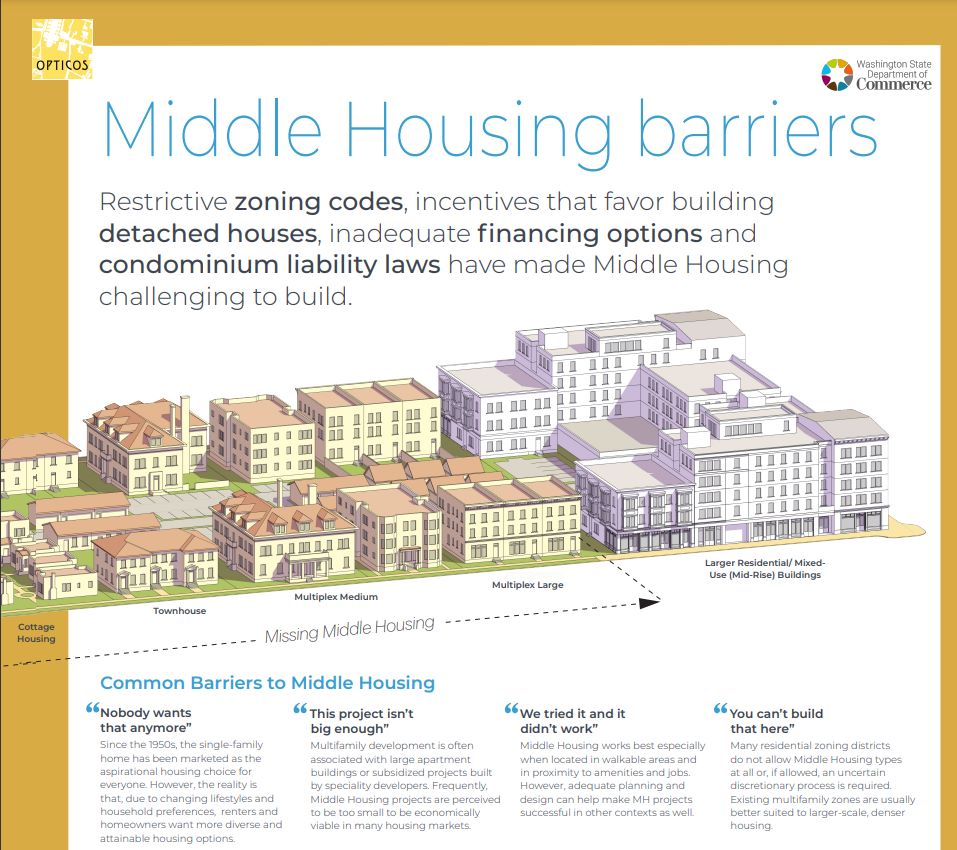

The issue is that the toolkit, rather than solving for affordability, feasibility, and the lowest carbon footprint, is primarily focused on crafting development guidelines that will keep new infill development the size of average houses and thus minimize the outcry from vocal neighbors. While this might be an easier to swallow approach for Washington cities and towns, it doesn’t scale up to address the deeper issues that HB 1110 was passed to address: the massive shortfall of new places for people to live.

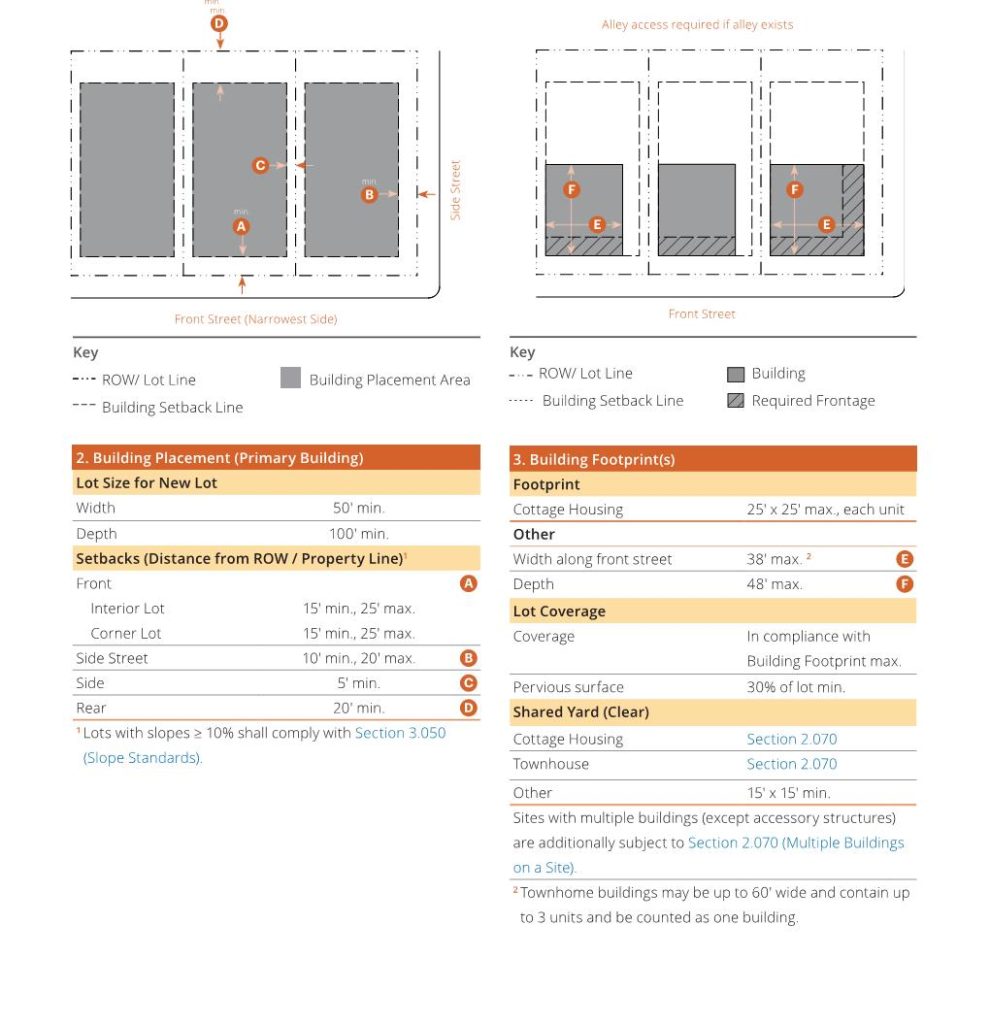

While Commerce’s original intent was to come up with instructive materials broadly applicable to most local governments, the effort lags behind what more progressive jurisdictions are already doing. But when we dig into the details, the toolkit suggests real reductions in development capacity: smaller footprints, bigger setbacks, and lower roof heights than are currently allowed in many Puget Sound cities. At its very worst, it will give slow-growth municipalities the option to select a new zoning overlay that is more prescriptive and restrictive, thus spoiling any chance that any new middle housing will be built.

Let’s go through the proposed new toolkit and look at some of the underlying flaws.

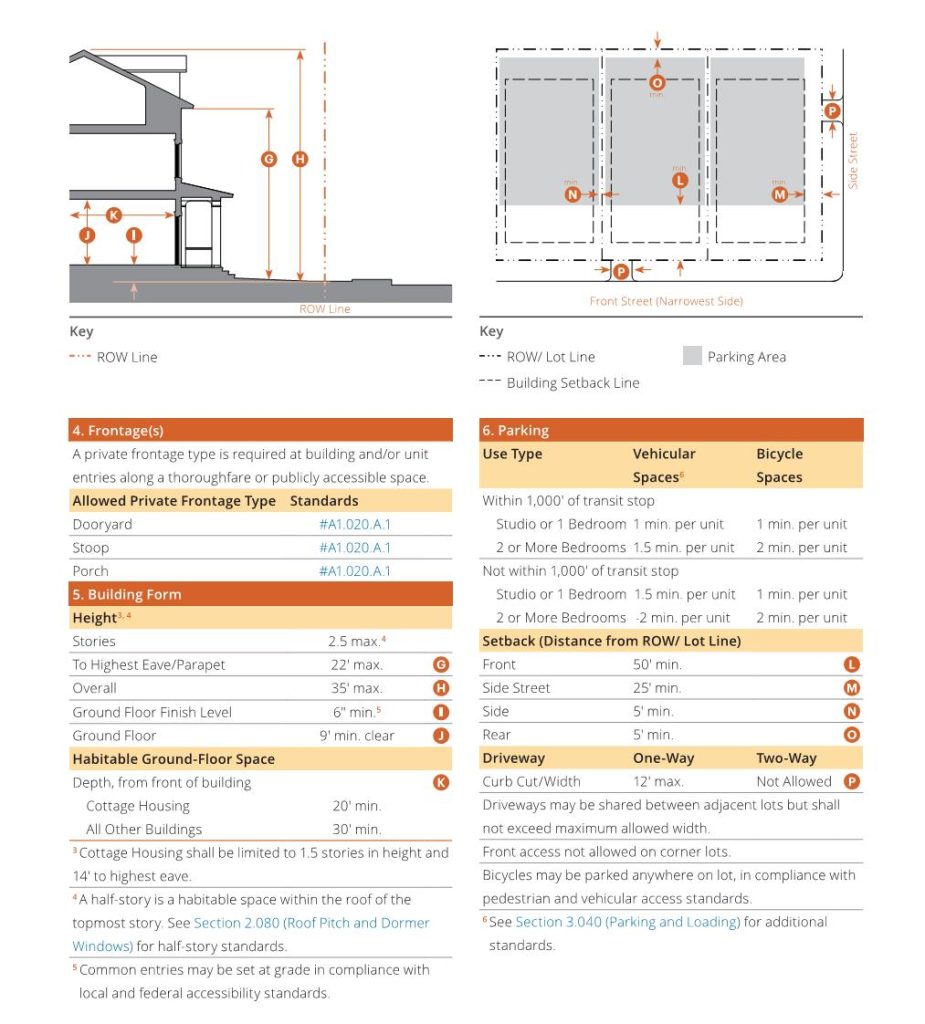

- They state, “This toolkit does not provide standards for buildings taller than three stories.” For three of the four overlays in the Toolkit, buildings are conceived as two and a half stories with a height bonus for hip and gable roofs – less that most of Washington cities’ least dense residential zones today. Rather than proposing an actual incremental increase, it ignores the status quo as a starting point. If you want a single pitch ‘shed’ roof, the 22-foot height limit is actually less than what we allow for a backyard cottage in Seattle today.

- Parking is mandated throughout the toolkit, a reversal for many jurisdictions that are moving away from required off street parking. Indeed one of the strengths of HB 1110 is releasing parking restrictions for new housing.

- Most overlay zones top out at four units per parcel, equivalent to Seattle’s second least dense zone, Residential Small Lot. Much of the ‘middle’ housing that is missing is between a house-sized triplex and the ‘5 over 1’ medium-sized apartment building. While this toolkit focuses on redundant standards for housing types we already allow, like townhouses and triplexes, it is silent on helping planners visualize appropriately-scaled urban buildings that might have between six to twenty units.

- Townhomes today, for better or worse, are the least expensive middle housing alternative available in the market, and the toolkit hamstrings their development with provisions that limit the number per building and the building length. The most successful rowhouse style homes on corner lots wouldn’t comply.

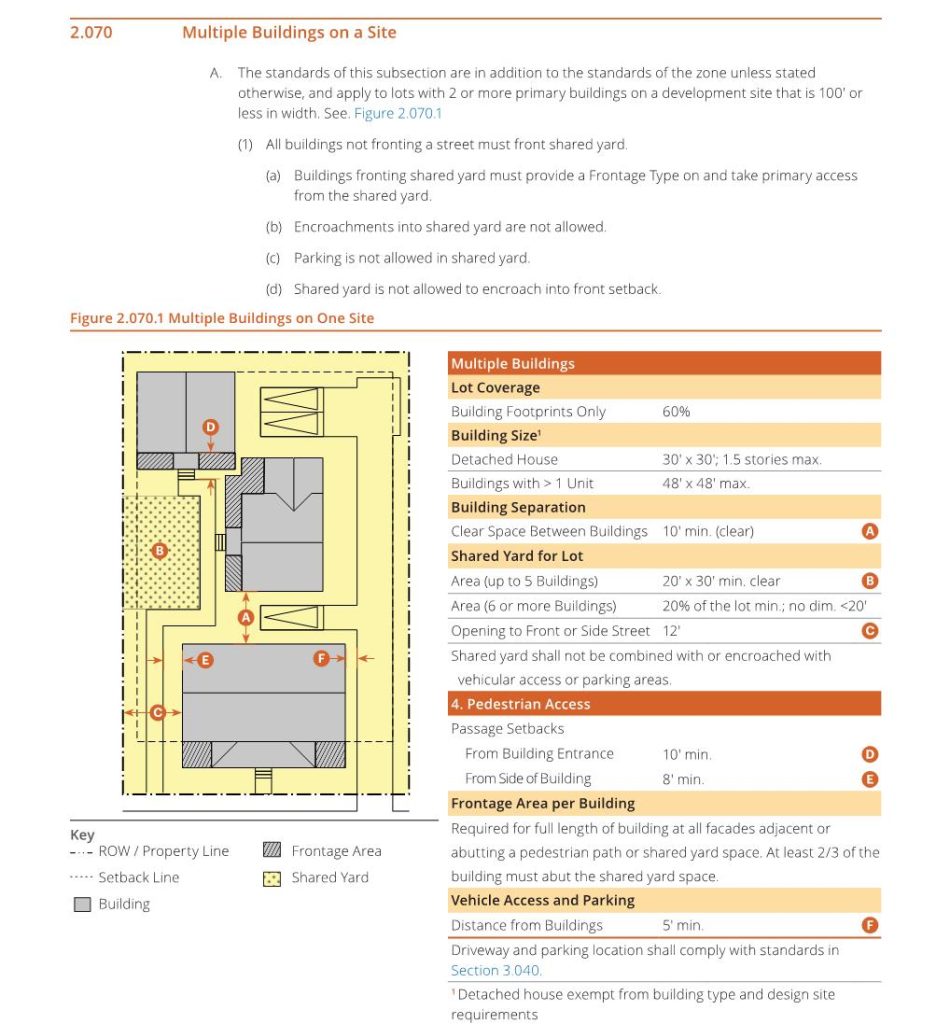

- The toolkit increases barriers for sites with multiple buildings on a single site, which would render many currently popular types of middle housing, such as detached townhouses, cottage clusters in Residential Small Lot zoning, and arguably even detached accessory dwelling units nearly impossible to build on compact urban lots.

- The toolkit does not provide flexibility for sites that might want to preserve existing housing and build more. It assumes parcels are cleared rather than provide provisions for new buildings in the backyard, lot splitting, or additions that add units.

- While much of today’s urban design discourse is centered around neighborhoods where goods and services are accessible within a 15-minute walk or roll, the toolkit doesn’t have any provisions for mixed uses like daycares, commercial suites or corner stores.

- Finally, as one gets into the details of each overlay, it is chock full of reductions: larger setbacks, less lot coverage, less height, larger minimum lot areas, prescriptive design standards – each taking a bite out of the viability of future housing. When we compared a fourplex we’re currently designing in Spokane against the toolkit, we’d need to reduce the footprint by 32%, lose the front and back porches, and downgrade the 2-bedroom units to 1-bedrooms.

Unlocking the residential potential of urban land is critical if we’re going to provide the more than 1.1 million homes Washington State projects we’ll need over the next 20 years, and that means reintroducing multi-family housing types that exclusionary zoning has regulated out of existence.

With this upcoming model code, we can take a good hard look at how new infill development is built, but we first have to move past the idea that middle housing is house-sized buildings carved into more apartments, or cottage clusters. Overall, the toolkit’s conceptual limitations and prescriptive ‘objective standards’ don’t reflect the real conditions of Washington neighborhoods.

A more serious effort would worry less about what neighbors might think and center our goals of housing abundance and climate action leading with middle housing types that work all the way up to four- and five-story mid-sized buildings in keeping with the best practices of urban planning around the world. Washington needs a flexible model code that supports the big picture goals of abundant housing.

Matt Hutchins

Matt Hutchins is an advocate for housing abundance, smart growth and sustainable architecture. As a Principal at CAST Architecture, he is working on innovative housing options, from cottages to co-housing.