A trip to Cedar Hills Regional Landfill shows garbage’s disappearing act is an illusion.

There’s a great episode of 99 Percent Invisible that compares residential waste collection systems in Taiwan and the US. In Taipei, garbage and recycling trucks run their routes multiple times a day, playing distinctive classical music, and at each stop wait for residents to throw in their own garbage bags and sort their own recyclables. It’s a system that forces residents to reckon with the volume and types of their waste.

In the US, our solid waste disappears soon after we create it. We put it in bins or dumpsters outside and then pay someone else to do the dirty work. We might reckon with the amounts we’re creating when we pay the bill according to bin size or type, or we might live in places like Seattle where all recycling collection is free. Regardless, as soon as our refuse enters these bins, we don’t have to think about it again.

But where does it all go? And how much of it is there? In King County, while our garbage is kept out of the way, it’s not far away, and there is so much of it that we are running out of space in our landfill to store it. Despite this looming crisis, most of what we throw away could have been diverted from the landfill and reused, preserving precious landfill space, resources, and creating new value. We cannot continue to expect our garbage to simply disappear without someday dealing with the big reveal. Not only do we risk letting it erupt into our landscape, but we also fail to see how it can stabilize our supply chains. So let’s keep it in sight. To do that, we first need to find it!

Behind the Curtain

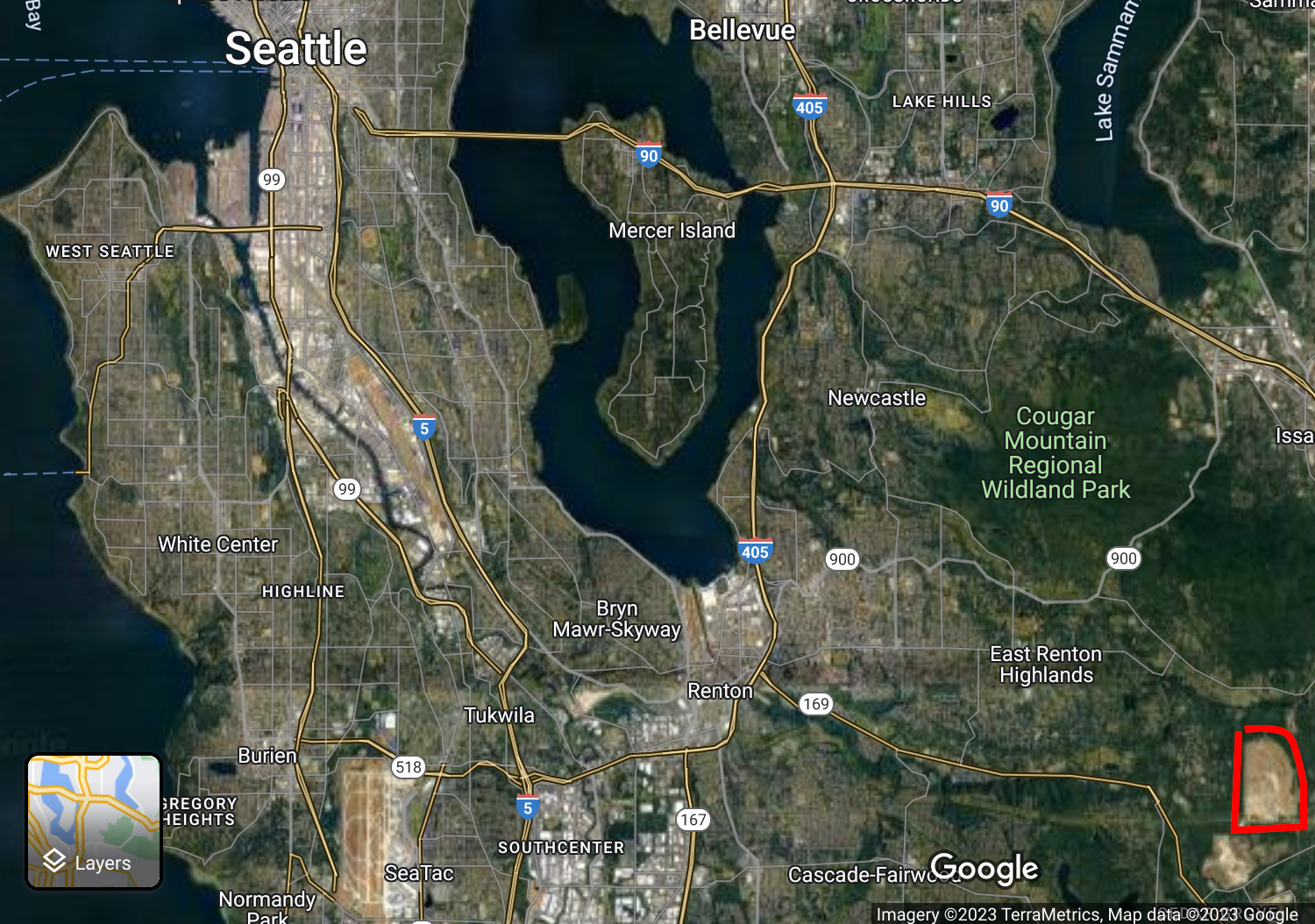

Tada! Look at the red outline in the bottom-right corner of the map below. If you live in King County (except Seattle and Milton, more on that later), most of your garbage goes there, to the Cedar Hills Regional Landfill.

Just south of Cougar and Tiger Mountains, weekend favorites for many hikers in the area, rises another range (or perhaps a monument), the Cedar Hills Regional Landfill. The 920-acre site amasses an additional 1 million tons per year, storing the garbage from about 1.5 million people, or 68% of King County, as of May 2022. The population that this humble dumping ground serves is expected to increase, as King County grew by an average of over 3% annually from 2010 to 2020 according to the US Census Bureau.

The Landfill is … Filling

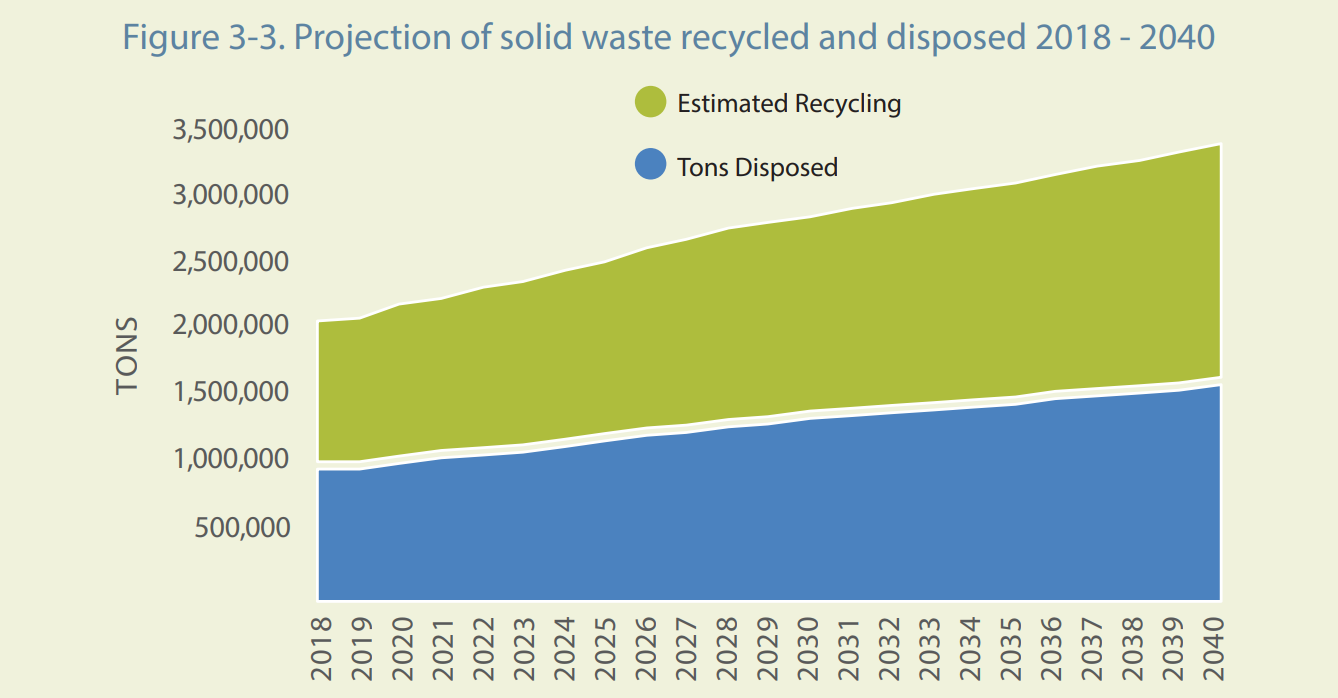

How will the landfill manage future population and waste growth? The King County Solid Waste Division (KCSWD) answered these questions in its 2019 Comprehensive Plan. They estimated that annual garbage production will increase up to 1.275 million tons by 2028 and 1.564 million tons by 2040 (“Tons Disposed” in the figure below).

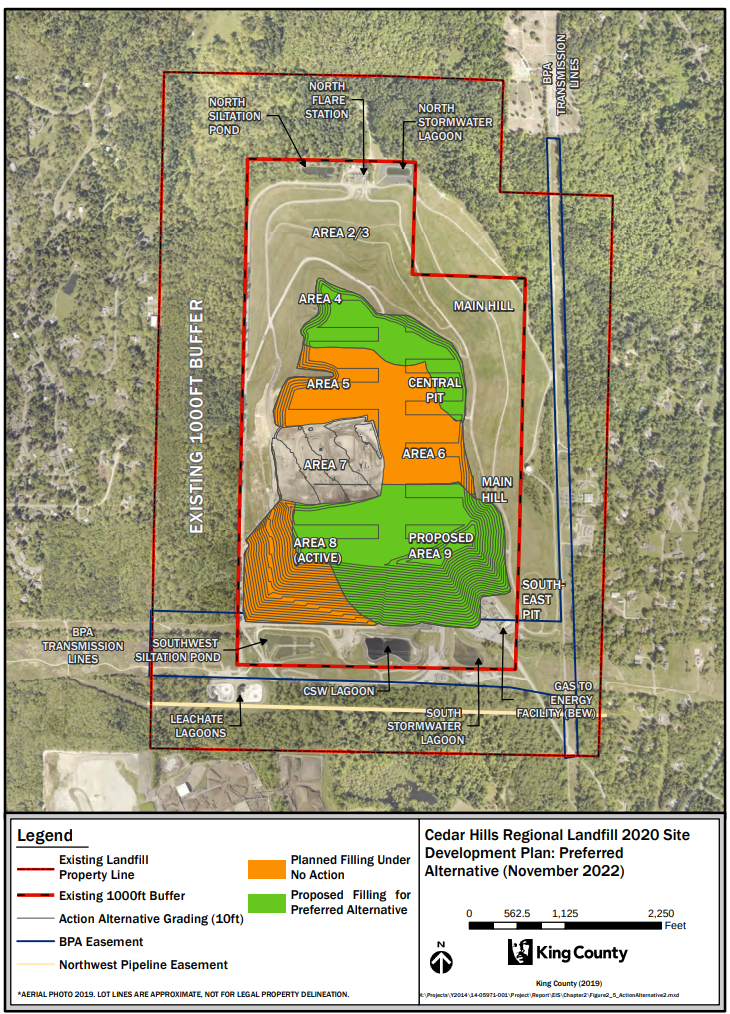

The truth is that Cedar Hills is running out of space. In fact, when the 2019 Plan was published, the landfill was estimated to reach capacity by 2028, but in 2022 the county decided to expand it, kicking the proverbial can of deciding where to put our post-Cedar Hills trash 10 years down the road.

The adopted expansion plan created a new 34-acre Zone 9 in the landfill, for a total active area of about 500 acres, and also permitted the waste to pile up to 30 feet higher than before, from 800 feet to 830 feet above sea level. Since Cedar Hills is about 630 feet above sea level, that’s about 200 feet above the ground.

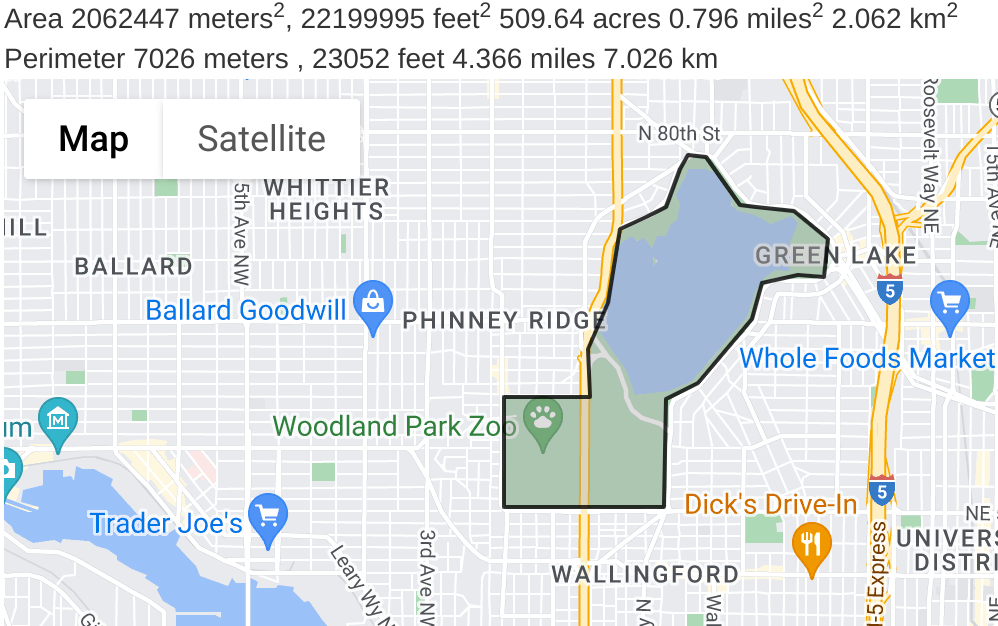

To get a sense for how large this landfill will be when it’s at what’s currently defined as full capacity: imagine Green Lake and Woodland Parks in Seattle (including the zoo) completely filled with garbage up to a third of the height of the Space Needle (605 feet at the top of the spire). The average density of the pile would be about the same as solid butter.

Wasted Opportunities

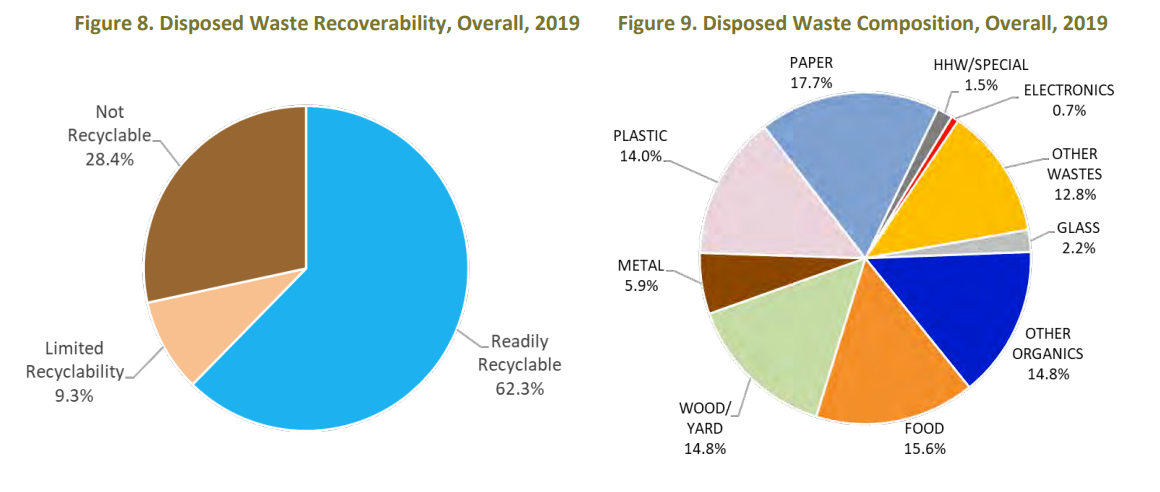

If the thought of the entire area of Green Lake and Woodland Parks filled up to 200 feet high with trash (or butter) doesn’t fill you with disgust (or awe), then maybe this will: that 62% of the new garbage in the landfill could have been diverted! The 2019 Waste Characterization Study concluded that most of what we threw away was “Readily Recyclable,” meaning that it could have been recovered in recyclables or organics waste streams (see Disposed Waste Recoverability chart on left, below).

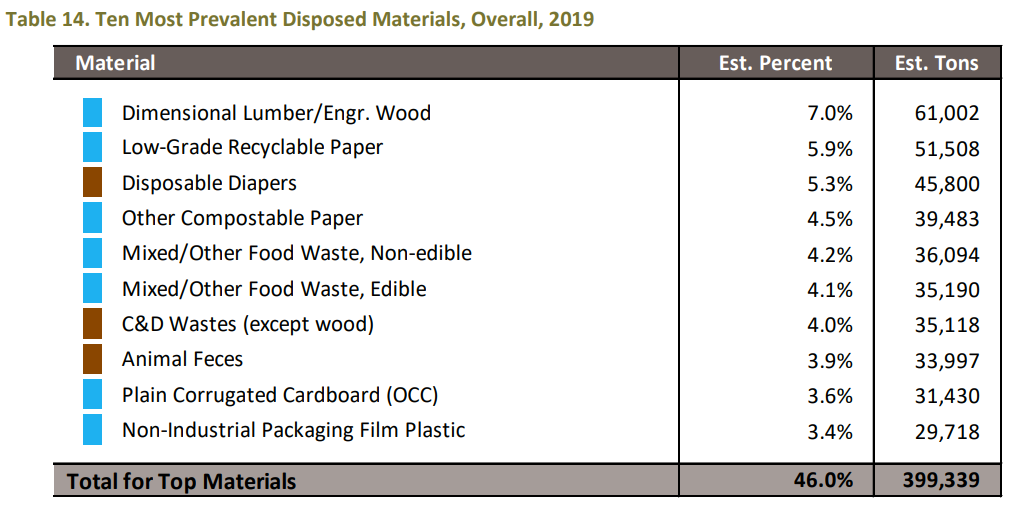

As the Disposed Waste Composition chart on the above right shows, a large portion of the recoverable waste is in the organics category (Wood/Yard, Food, and Other Organics, almost half!); furthermore, as the chart below shows, seven of the top ten most common materials were recyclable (materials with blue rectangles). Note that samples were collected from all over the county, and a couple facilities do not offer recycling and organics collection. The facilities also collect residential as well as commercial waste, but the overall results are similar to residential-only results.

Dirty Diapers

Landfills are federally mandated to include thick liners to prevent leakage into the surrounding soil and groundwater. Furthermore, they are covered daily in order to reduce odor, prevent fires and scavenging, and to recover methane that is released from the large amount of decomposing organic waste.

The fact that they contain large contributions of disposable diapers and pet waste (see table above) adds literal to their figurative purpose as the dirty diapers of society. The thousands of people who live around the 1.4 square-mile diaper that is Cedar Hills Landfill will always have to deal with it, and eventually we’ll have to create a new landfill. We can’t pretend that new landfills are never going to be sited in our future backyards or, more likely, that it’s okay to keep siting them in the backyards of those who already deal with their fair share of toxic and smelly sites. Indeed, the origin of the Not In My Backyard (NIMBY) movement has its roots in toxic waste management.

There are real opportunity costs to landfills, the first being healthy land. The protective measures mentioned above are designed to prevent infiltration, not to restore; the land will not be productive again as long as there are hundreds of feet of garbage underneath it and surrounding areas will remain devalued. Second, as the charts in the last section show, the landfills are filled with natural resources that could have been recovered, creating jobs and new products; instead, these resources remain inaccessible.

This, in my opinion, is the most potent smell of the status quo: that we are wasting valuable resources. It’s painful for me to think about the investments we’ve made as a society to grow an incredible diversity of food and to extract chemicals from fossil fuels and mines, only to choose every year to lock many of these resources away in landfills. As worldwide demand for these resources changes, I believe this wasteful pattern will lead to higher prices and more conflict. The 2019 Comprehensive Plan assumed a 52% recycling rate through 2023. This is like running an engine at 50% efficiency; imagine if half the gas you paid for and put in the tank was simply dumped on the ground! For systems that we use every day, this kind of inefficiency is increasingly expensive and unacceptable.

Opportunities of Waste

What can we do to slow the creation of new landfills and in the process create circular waste economies, where more materials are recovered and reused, and our waste is not so wasteful? I posed this question to Sergio Barbosa, KCSWD Operations Supervisor, while on a tour of the Bow Lake Transfer Station. He advocated for three things: changing incentives, improved facilities, and, most of all, education for residential customers to better sort and process their solid waste.

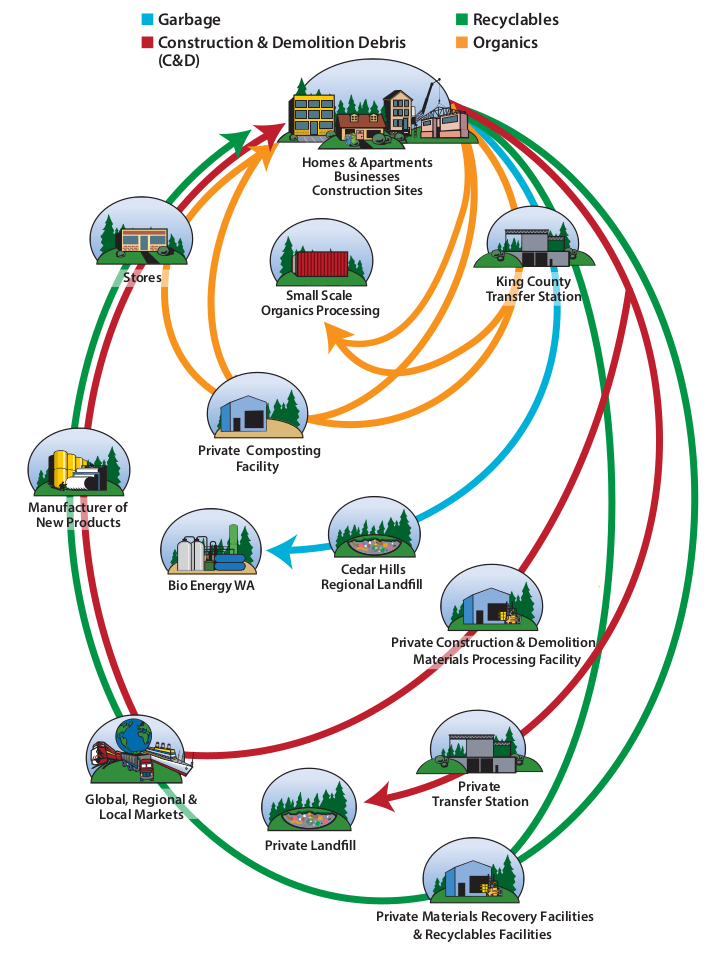

A transfer station, as the diagram above shows, is where haulers of all kinds bring their trash, recyclables, organics, and other valuable or hazardous products like appliances. Looking at the mountain of trash that had been dumped on the floor by commercial haulers, I could not help but notice the large number of recyclables just sitting on the top of the pile, mostly cardboard boxes. A loader shuttled back and forth, tirelessly pushing the waste into a corner where it would fall through the floor to be compacted and then taken to the landfill. Barbosa noted that this loader runs all day to keep up with new deposits.

Meanwhile, on the side of the floor, individuals stood in the backs of pickup trucks, throwing more trash but also more recyclables into the pile: mostly wood, but also perfectly good-looking furniture. These people were paying more to just throw everything into the trash, rather than bothering to make another stop, whether that was at their local donation center or the used wood collection bin 50 feet away. While I’m sympathetic to those who don’t have this luxury of time, I was disturbed by the pressures, ignorance, and indifference that drive this behavior.

At home, I researched Barbosa’s recommendations and found that the county has recognized the problem and is already taking action. There’s never been a better time to join the movement towards a more circular economy.

Investments

It’s encouraging that King County has a stated goal to “keep 70% of materials with economic value out of the landfill” as part of its newly launched Re+ program. What’s more, this March they put their money where their mouth is, awarding $2.3 million in grants to 14 projects that can help them reach this goal. The projects span the entire value chain and a variety of “waste” sources, from connecting surplus food with chefs to mixing post-consumer plastics into asphalt for roads. It’s a drop in the bucket of their total $357 million budget for this year, but it’s something.

The county is also wrapping up a pilot that uses a new Materials Recovery Facility (MRF) technology called Juno. Juno has the ability to capture cups with plastic coatings and contaminated paper-based food packaging, tripling landfill diversion rates in other areas that it has been used.

Education

One thing that I won’t forget about recycling after learning about MRFs is that it’s better to not bag your recyclables, especially in opaque bags, because the machinery cannot process it and workers often do not have time to open the bags. Sadly, these bags full of perfectly recyclable material that you took the time to sort may end up in the trash. As of 2020, King County no longer accepts plastic bags in curbside bins, and neither does Seattle.

Similarly, unless the downstream MRF can handle “wet” inputs, like those using the Juno technology, it cannot handle recyclables that are commingled with food waste. Usually these recyclables are deemed contaminated and have to be thrown away. That is why many recycling services require that your recyclables are unbagged, clean, and dry.

Coincidentally, contamination is the reason that China’s National Sword policy was so impactful to the recycling economy in the US. The policy did not ban imports of recyclables outright, it just raised the quality standards of those imports, forcing the US to deal with its inventory of contaminated and even toxic materials. For many years, China was effectively buying garbage from the US, materials that would have just gone straight to the landfill otherwise. The problem is not that someone else is not buying our food-covered takeout containers; it’s that we’re producing so many without the ability to reclaim any value from them.

Speaking of waste that’s difficult to deal with, what do you do with the spectrum of unidentifiable plastic in so many goods and their packaging? In the past I’ve optimistically put much of it in the recycling bin, a practice called wishcycling. Unfortunately, our current facilities cannot process many of these plastics and when in doubt, they should be thrown away to prevent contamination. However, there are tools available, such as King County’s What Do I Do With…? and Seattle Public Utilities’ Where Does it Go? that may be able to provide other options.

I was shocked to learn that there are businesses in King County dedicated to recycling mattresses and rugs into new products! Organics waste is transformed into high-grade compost, locally, at Cedar Grove. Plastic bags and packaging film can be turned into new composites through programs like Seattle WRAP. Refrigerator coolants, which can be thousands of times more potent greenhouse gases than CO2, are purified and resold by Total Reclaim.

Upstream Interventions

The above interventions deal with the products that we have already created. They place a lot of responsibility on consumers and a lot of hope on future technology. But what about the manufacturers who made the product, or designed it in a way that makes it difficult to put it anywhere but in the trash?

As consumers we have the power to choose to buy and use products that create less solid waste, or less unusable solid waste. Of course, manufacturers are aware of this and there is a good amount of greenwashing going on, so you need to do your research. The petrochemical industry will keep on lobbying to make everything from cheap, ubiquitous, and difficult to recycle plastics. Buying used or even not at all is a good way to avoid dealing with the personal cost of dealing with the disposal of a new product.

When market(ing) forces are too strong, our lawmakers can also step in. We have already controlled the sale of some harmful materials in products and packaging, such as HCFCs (refrigerants) and PFAs (nonstick chemicals used in food packaging). Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programs force manufacturers to be responsible for disposal of their products.

Out of Sight But Not Mind

What will we do with our trash when the Cedar Hills Landfill closes? Most likely, it will be shipped to Oregon. This is the fate of Seattle’s trash today. The Columbia Ridge Landfill has a currently active size of 700 acres and processes an estimated 2.8 million tons of trash per year.

The trash is transported by train. Regulations require that each train only carries trash, on average 300 double-stacked containers weighing an average of 48 tons each. That’s a lot of trash, even to imagine. But when the roar and grumble of the engine fades into the distance, it’s as if it never existed; the trash stays invisible, hidden behind an illusion that we can just continue to create waste the way we do now without ever paying its full cost.

This article is a cross-post from ricehornet, a blog by Eric Thorne, who is a software engineer living in Columbia City.

Eric Thorne

Eric Thorne is an electrical-turned software engineer living in Columbia City in Seattle. He writes and illustrates to help him understand the world and how he feels about it. He feels strongly that cities can host human and natural systems that are safe, inclusive, efficient, and open to change as our world continues to change.