However agency leaders displayed hesitancy to inconvenience cars to build transit more efficiently.

On Thursday, the Sound Transit Board pressed the agency’s heads of corridor planning to defend their property-takings-heavy approach, which was revealed when The Urbanist published leaked Everett Link concepts on Tuesday. Their answers revealed some costly assumptions that are likely to drive up project costs for Everett Link and other extension projects in the works while leading to worse outcomes for riders and the neighborhoods around the station.

Summer malaise appeared to be in full force when the Sound Transit Board met on Thursday. The board barely had a quorum to complete its items of business, which forced Chair Dow Constantine to interrupt a staff presentation to press through several votes while they did cross that threshold. Among the absent boardmembers were Snohomish County Executive Dave Somers, Everett Mayor Cassie Franklin, and Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell, who missed his second straight board meeting.

Nonetheless, Boardmember Claudia Balducci’s questioning showed at least some board interest in trying to refine the Everett Link plans to avoid unnecessary property takings that will cause displacement while ballooning project costs, risking further delay of the project. Eric Widstrand, Director of High-Capacity Transit Corridor Development, and his boss Don Billen, who is the head of Planning, Environment and Project Development, were on hand to answer for the Everett Link planning efforts thus far.

“There’s been a lot of public input with regard to how some of these options assume that you maintain the road width exactly as it is today without putting any stanchions in it or anything,” Balducci said. “And then we have a lot of takings in order to do elevated [guideways] that could be done in the roadway. My question is this: by taking this action today, are we still able to look at those corridors through the DEIS process, and consider options that would follow those same alignments, but might be narrower and limit the takings and consider use of public right-of-way where that is possible and appropriate?”

Widstrand began by replying, yes, but then came the caveats.

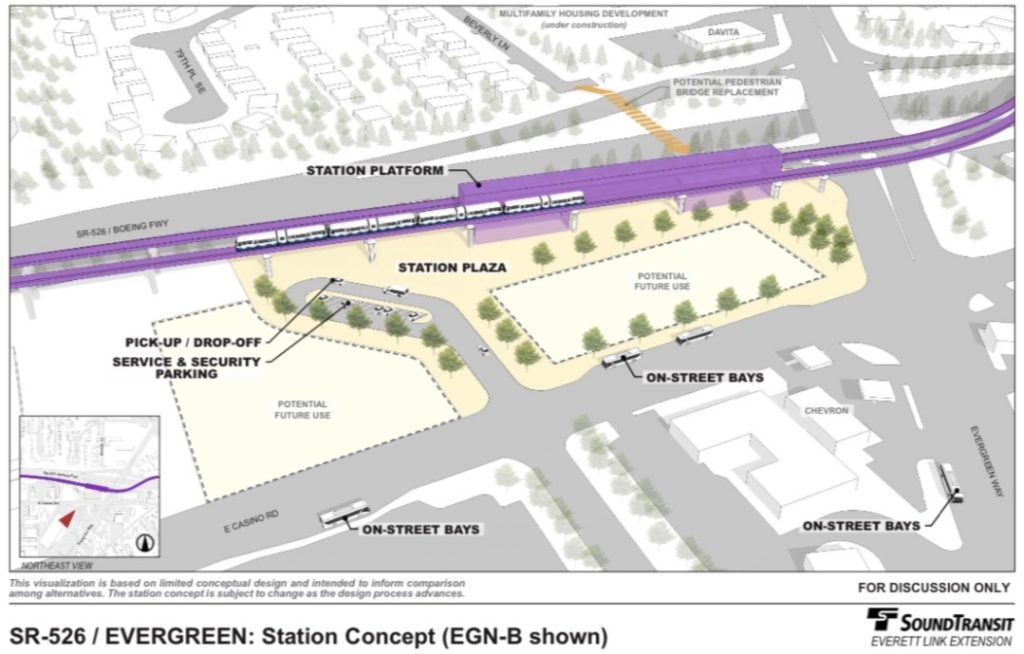

“In Phase 1, there were several segments of the project that we did look at in-road alignments with an elevated guideway,” Widstrand said. “These were along Casino Road between Southwest Everett Industrial Center and the Evergreen station area. Those in-road alignments were screened out based on feedback from the public and technical challenges related to traffic operations, and right-of-way impacts as well. We also looked at another segment in downtown Everett along Broadway. This was an option that was also screened out during during phase 1. Those options, for other parts of the corridor, are not precluded from looking at that. But Sound Transit will work collaboratively with our jurisdictional partners to coordinate our alignment with their transportation networks.”

Balducci did not seem to appreciate the caveats.

“I was so happy right up until your last sentence,” Balducci said. “I want to make sure that we have the opportunity to and that this will happen without something else being another direction needing to occur. And that is the problem here if we vote on this right now, as is the some other direction that needs to happen in order for those options to be kept alive and studied as part of the DEIS so that they can be proposed and commented on at the end of the DEIS.”

Widstrand replied, “I think those are still on the table.”

This was even less what Balducci wanted to hear. “I want to hear yes, and I’m hearing maybe and that’s not helping me,” she responded.

At this point Billen jumped in to try to make sense of a messy situation built perhaps on some regrettable agency assumptions baked into planning thus far.

“So, Boardmember Balducci, you’re hearing maybe because there are places where we will be able to refine the alignments as defined now to minimize impacts,” Billen said. “Some of the ideas that have been suggested in recent public comment are new alternatives that would require further study and board direction to advance.”

Given their tight meeting schedule with a handful of presentations and a half hour of executive session, Balducci tabled the issue for now, while urging follow-up work.

“Given where we’re at today, and I don’t want to hold this up further, let’s regroup after this,” Balducci said. “I think we should move forward today. You know, authorize and empower you all to start your work and not hold things up. But I do want to have a more in-depth discussion with a map in front of us about where we can create, revive, refine, whatever verb you want to use, options that will be less impactful, quicker to deliver, cheaper to deliver, and not have as many takings.”

Sound Transit’s corridor planning heads said they would welcome that conversation. In a 9-0 vote, the 18-member board then proceeded to approve station preferences for Everett Link that will advance to environmental study and planning for the project — just barely over the threshold for a quorum for this hugely impactful decision for the future of Snohomish County and the regional transit network writ-large.

While Balducci’s exchange with corridor planners may sound relatively tame for folks unfamiliar with how the Sound Transit Board operates, in fact, it qualifies as dramatic and exceptional. During public meetings, boardmembers rarely ask staff tough questions, probing for fundamental flaws or questioning assumptions. Many a presentation ends with essentially no questions at all. When tough questions do arise, it’s often Balducci doing the heavy lifting.

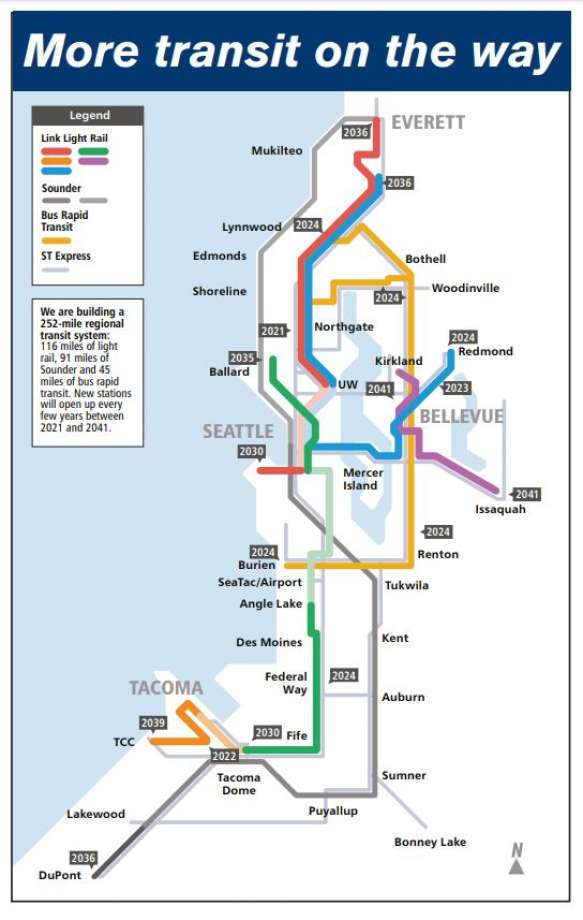

And make no mistake that Sound Transit is at a moment where tough questions are necessary and essential. Voters approved the $54 billion Sound Transit 3 (ST3) package in 2016 that promised an additional 62 miles of light rail and 45 miles of bus rapid transit on a certain timeline. That timeline has gone out the window due to planning delays, pandemic speed bumps, and construction cost escalation.

Several extensions are facing questions of further delays or jettisoning stations to cut cost and complexity. It may make sense to let go of low-ridership stations in the name of delivering projects sooner, but some of the stations on the chopping block include the highest ridership stations in the ST3 plan, including stations in South Lake Union, Midtown, and Chinatown.

For the Everett Link extension, one of the highest value stations, situated at SR 99 and Airport Road, is provisional, unfunded, and unclear how it will be added to the plan as the agency zeroes in on an expensive alignment crooking toward Paine Field and the sprawling Boeing campus. The cost crunch is made worse by the agency’s refusal to take right-of-way from cars along wide arterial roads and highways, which leads to expensive property takings to site the transit line and leaves people walking, rolling, and biking with wide, dangerous, and high-speed roads to cross to reach stations.

The board just approved $71 million for a new parking garage in Auburn. The parking garage is a gross waste of public funds. https://t.co/YNIl9ac9OO

— The Urbanist (@UrbanistOrg) June 22, 2023

At Thursday’s meeting, agency staff also daylighted a further 6- to 12-month delay to the entire Stride bus rapid transit program program, which was supposed to be an early deliverable of ST3, as Chair Constantine ruefully pointed out. This delay was on top of a similar delay already announced in April. It appears the three Stride lines will not be operational until 2028, despite their initial 2024 promise.

The agency’s outside consultant, Dave Peters, also presented and told the agency it was in desperate need of reforming its culture, structure, and practices, echoing a similar set of recommendations from the agency’s Technical Advisory Group from earlier this year. By this point in the meeting, even the narrow quorum the board had mustered was gone and the sobering report fell on a small fraction of the board’s full strength. Those absent will hopefully go back and review the recording and materials.

Peters noted that Sound Transit's parking structures cost twice what the private sector pays.

— The Urbanist (@UrbanistOrg) June 22, 2023

Incidentally, the Board approved a $71 million Auburn parking garage today.

Peters told the board that the agency’s parking structure costs are twice that of the private sector. Nonetheless, the agency has continued to pour money into structured parking that has a low return on investment in terms of riders. At the same meeting, the board approved a $71 million for a second parking garage next to its Auburn Sounder train station.

Sound Transit CEO Julie Timm seemed to sense the frustration building among transit advocates and shared some of the work she is doing behind the scenes.

“There’s plenty of opportunity for improvements in our culture and process,” Timm said in a tweet. “If I’m quiet about it, it’s because I’m doing internal work that needs some time and sensitivity. Good Team, challenging issues, improvements being sown. Change is hard – but it’s happening!”

The change in leadership at the top of Sound Transit offers a glimmer of hope, but it’s going to take leadership from the board as well for momentum to be built and sustained.

It is time for the region’s transit leaders to ask: ‘What are we doing here?’ And then ensure better practices are put into place.

Unfortunately, few board members are engaging with those questions as is their responsibility as stewards of a multi-billion-dollar agency. The board needs more members bravely asking those questions and demanding answers like Balducci has. Until they do, it’s hard to see how they will get out of the rut they are in that has ST3 hurdling toward disaster.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.