Mayor Harrell may have come around on the Youth Violence Prevention Initiative he helped defund during his time on Seattle City Council.

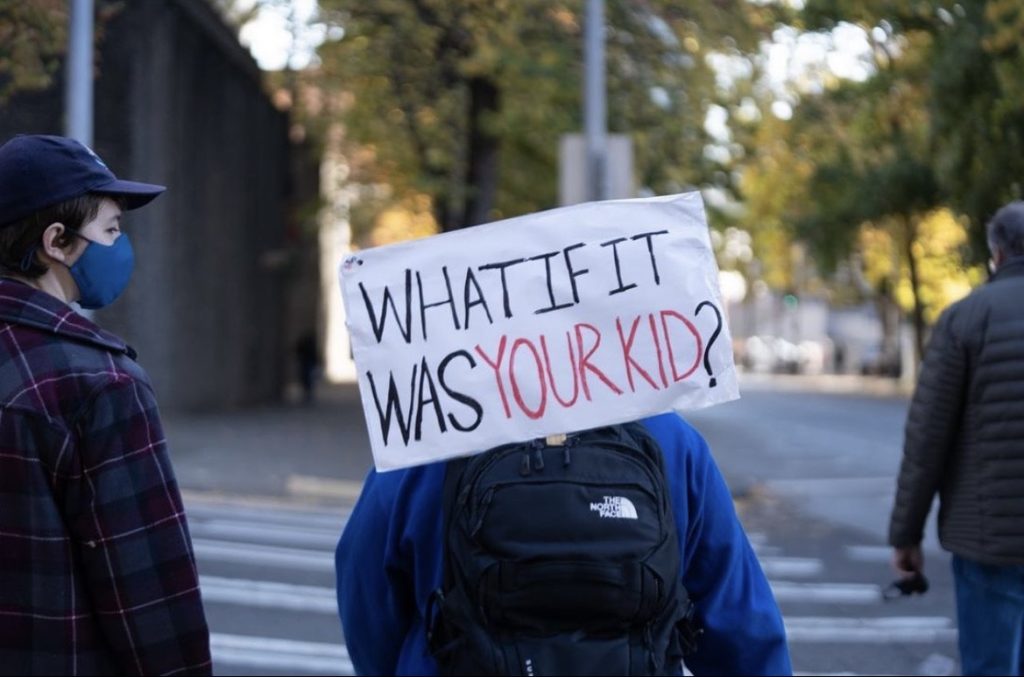

In 2020, guns became the leading cause of death for US children and teens for the first time in history, and Seattle’s high school students are begging for more investment as gun violence continues to negatively impact their safety and education.

“We never thought gun violence would come all the way to Seattle,” Franklin High School junior Natalya McConnell said. “It is so scary to all of a sudden realize you could be the next person dead.”

In the latest incident, Garfield and Nova High Schools, located in the Central District, ended early on June 1 and switched to remote learning for June 2, remaining closed through the weekend. The Superintendent of Seattle Public Schools (SPS), Dr. Brent Jones, confirmed the closure was due to information received from credible sources of a threat of gun violence planned for after dismissal near the Garfield and Nova school campuses. This closure occurred after three incidents of gun violence near the school in the preceding two weeks.

This continues a trend of gun violence impacting Seattle area schools, including the closure of Franklin High School in December of 2021 and the fatal shooting of student Ebenezer Haile at Ingraham High School last fall. In response, city leaders announced a new $4.5 million Student Mental Health Supports pilot. Five SPS schools received $125,000 this year, and the rest of the money will be dispersed over the next two school years, with additional schools to be added; Garfield and Nova High Schools aren’t currently on that list.

In addition, the Mayor recently announced a new youth mental health initiative emphasizing psychological first aid and community learning programs, although the initiative doesn’t include any new funding.

“Until there is money attached to this program, nothing much is going to happen,” said McConnell. Thus far, little progress to better support students’ mental health has been made, even if advocates like McConnell are heartened that the fledgling program could be a step in the right direction.

In addition to the harm to their mental health, students are reeling from the impacts of gun violence on their ability to learn well at school. Dr. Jones says gun and community violence “impacts our students’ mental health and reduces their ability to focus on learning.” The recent closure of Garfield was particularly disruptive being so close to the end of the school year, when students are rushing to finish final projects and prepare for important tests and finals.

And it was hardly an aberration. Earlier this year, students at Franklin High School experienced several days of shelter in place, preventing them from changing classes and being able to finish assignments.

Research shows exposure to gun violence and violent crime “can affect students’ educational attainment, grades, test scores, graduation rates, and academic engagement” and students who experience gun violence at school experience higher rates of absenteeism, lower graduation rates from both high school and college, and lower wage earning in their mid-20s.

This is occurring during a period when the mental health of U.S. high school students has taken a drastic downturn. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that in 2021, 37% of high school students reported they were experiencing poor mental health, 44% reported they felt persistently sad or hopeless in the past year, and a whopping 55% reported experiencing emotional abuse by a parent or other adult in the home. US Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy released a report on youth mental health in 2021.

“The challenges today’s generation of young people face are unprecedented and uniquely hard to navigate,” Murthy wrote. “And the effect these challenges have had on their mental health is devastating.”

Gun violence is commonly recognized as a childhood adverse experience (ACE), which tends to leave lasting traumatic impacts due to the heightened sensitivity of the brain during childhood and adolescence. ACEs are known to have lasting negative effects on both physical and mental health, wellbeing, and access to opportunities. During a recent press conference, Chetan Soni, a junior at Lincoln High School warned of the toll this upheaval was having on students.

“Once students realize the crushing weight of the world’s problems — climate change, mass shootings, huge economic disparities, Covid-19, and I’m sure there’s more I’m missing — things start to get hopeless,” Soni said.

Dr. Leslie Walker-Harding of Seattle Children’s Hospital added further local context, saying, “Not only has the pandemic had an enormous impact on youth mental health, but it’s also created additional barriers and challenges to access for treatment. The CDC estimates that only 20% of youth who have a diagnosable, treatable mental health condition actually are able to talk with a mental health provider, and what’s so heart-wrenching about this is that even that 20%… is really overwhelming our mental health system as it is right now. At Seattle Children’s Hospital we see and feel the impacts of this every single day.”

However, in spite of a lack of decisive action by elected officials, Seattle high schoolers are determined to fight for their needs. McConnell, a co-founder and Executive Board President of the Seattle Student Union, a local student activist group, cites the closure of Franklin in 2021 as one of the inspirations for starting the group. Since its formation in January of 2022, the group has organized for – and won – more funding for school counselors and a state-wide assault weapons ban.

McConnell, who organized her first protest in the fifth grade, is adamant about the importance of funding more mental health counselors for schools, as well as making sure there are fewer guns in the community in the first place.

“I don’t have faith in most elected officials nowadays because they’re not listening to us and even if they are listening, they’re not implementing what we’re telling them to implement,” McConnell said, adding she thinks both the City and the State should be providing more funding for mental health counselors in schools and plans to fight for that during the upcoming Seattle budget season and next legislative session. “A lot of students are awakening to the fact we need to fight for our own safety because adults are not fighting for us and that’s a scary thing. We should not have to skip school to fight for our own safety.”

Meanwhile, Public Health Seattle & King County (PHSKC) is currently spearheading an innovative regional approach to gun violence, implementing best practices and evidence-based techniques for reducing gun violence in the community. Their public health strategy to address gun violence includes looking at root causes and compounded and generational trauma, as well as engaging those at highest risk of being impacted by gun violence and attempting to alter their conditions. This place-based approach involves creating a new model of frontline health workers in the community violence prevention space, including violence interrupters, hospital-based interventionists, and people with lived experience and community credibility.

“Community closest to the issue is closest to the solution,” said Eleuthera Lisch, the inaugural Director of PHSKC’s Gun Violence program.

Thus far national gun violence prevention programs have a strong track record. Following implementation of Operation Peacemaker in Richmond, California, the city saw its violent crime drop 66% from 2010 to 2017. One study of hospital-based violence intervention programs found those enrolled were six times less likely to be re-hospitalized for a violent injury and four times less likely to be convicted of a violent crime.

Chicago’s CREED program saw a 50% reduction in gunshot injuries in those enrolled within 18 months, and CURE Violence programs adopted in cities such as Baltimore, New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago have seen violent crime drop by more than 30%. The CURE Violence program in the south Bronx saw a reduction in shooting victimizations of 63%. All of these programs address the root causes of gun violence: poverty, trauma, and systemic racism against Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic communities.

Specific local gun violence prevention programs include the Regional Peacekeepers Collective, which works extensively with Harborview Hospital and community members impacted by gun violence, and a hub-based approach implemented through the Seattle Community Safety Initiative that is currently being expanded to South King County. PHSKC and Seattle also support the Rainier Beach Action Coalition’s Restorative Resolutions program. Meanwhile, both Seattle and King County support upstream prevention techniques, like Best Starts for Kids in King County and youth mentoring programs and a summer youth employment program in Seattle. Lisch said, “We stand with our young people. We want their safety and well being above all.”

All these measures – violence prevention, upstream solutions, and more mental health care for our young people – urgently require further investment. Seattle is only currently investing around $1.5 million in the Regional Peacekeepers Collective, $4.3 million in the Seattle Community Safety Initiative, and has taken over a $2 million investment into the Restorative Resolutions program in 2023. In 2022, the budget for all of PHSKC’s investments into gun violence prevention, which included contributions from Seattle, only totaled $6 million.

Such small investments pale in comparison to the $374.3 million Seattle Police Department and $514.9 million King County Sheriff’s Office budgets in 2023. And with a projected municipal budget crunch on the horizon, local governments might be tempted to eschew the important work of continuing to scale up these programs. Students have taken note of the dichotomy.

“Really the work is taxing the rich and defunding the police so we have money for student needs and community needs,” McConnell said.

Seattle first experimented with a youth violence prevention program with then-Mayor Greg Nickels’ Youth Violence Prevention Initiative in 2009, initially investing $8 million in the effort. Now almost fourteen years later, Seattle could have had a mature, scaled-up program; indeed, then-Mayor Michael McGinn fought to invest more into the program in 2012. At that time, then-Councilmember Bruce Harrell opposed the program; he was quoted by KOMO News as saying, “If you look at the effective change, we are still sort of falling short. You don’t just expand without some level of measurement.”

With Councilmember Tim Burgess’s help, the funding increase for youth violence prevention was blocked and stalled in a drawn-out audit process. Burgess is now a senior member of Harrell’s cabinet as “Director of Strategic Initiatives.”

Today we have a plethora of data showing the success of these programs, and President Biden is strongly in support of them, having announced a $5 billion investment in gun violence prevention programs back in 2021. But in spite of the pleas of our students, change – and substantial support for these evidence-backed programs – has been slow to come to Seattle. Come budget time, Mayor Harrell will have to decide if he is prepared to make the investments to match his rhetoric around the importance of the safety of our young people.

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.