Councilmembers Nelson and Pedersen, with scant evidence, claimed jail and forced treatment would make a dent in the opiate epidemic.

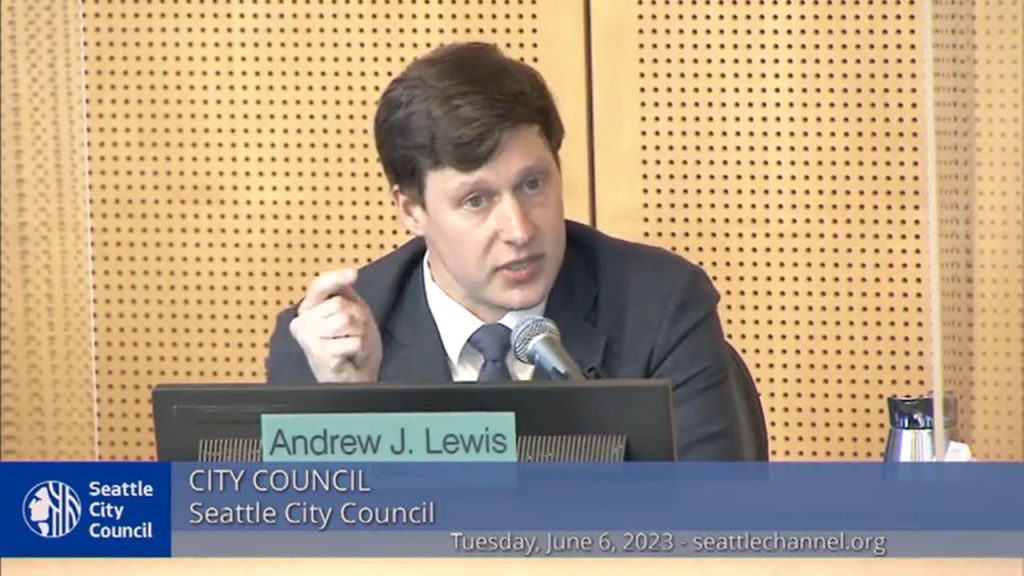

The push to reignite the war on drugs in Seattle came up short after a close City Council vote Tuesday. Councilmember Andrew Lewis appeared to be the swing vote, and said he moved to oppose the bill at the last minute after ultimately determining the legislation was rushed and the intent to pursue pre-trial diversion and drug treatment was unclear after the recent unilateral decision by Seattle City Attorney Ann Davison to end Seattle’s Community Court.

“I came out here on the dais today fully prepared to vote for this measure… but this discussion deserves more than this,” Lewis said, acknowledging the opiate epidemic is a huge problem affecting residents and business owners in his downtown-based district. “But with the ending of Community Court without any additional process, I just can’t do this today.”

Citing his experience as an assistant city attorney, Lewis said that Community Court was well situated to offer diversion and drug treatment services, despite some assertions otherwise from Davison and her allies. For him, that abrupt decision called into question sponsors’ claims that jail time was a last resort and drug treatment would be the focus.

“I can’t sit here when one of those tools is being taken away and the promise of pre-trail diversion hasn’t been fully fleshed out yet. I just can’t,” Lewis said. “Because I’ve worked in these systems, and I owe it to everyone involved to bring my experience to the table and daylight it. I just do. It’s more important than whether I stay on this dais, because real public policy matters on how we take care of this.”

That left sponsors with just four votes instead of the five they were counting on and needed to pass their bill. Councilmembers Lisa Herbold, Lewis, Tammy Morales, Teresa Mosqueda, and Kshama Sawant voted no. Councilmember Dan Strauss, who has often voted with progressives, voted with the conservative wing of the council to make it a close vote.

Strauss, Lewis, and Morales are up for reelection this year, while their four other district-based colleagues are retiring. Lewis referenced polling showing support for criminalization in his district and said that his vote could cost him seat, but he felt compelled to vote his conscience and supported evidence-based solutions rather than knee-jerk ones. On Wednesday, Lewis revealed he is working on an alternative proposal.

Davison proposed the legislation, which was taken up by Councilmembers Sara Nelson and Alex Pedersen. The trio announced their push on April 27, but had to modify their bill language in reaction to state drug legislation passed during a special session on May 16. The backers argued the need was too urgent to run the bill through the normal committee process, instead bypassing it straight to full council.

“The state law alone is an empty shell without the local law, and that’s the equivalent of decriminalization,” Pedersen claimed ahead of the vote Tuesday, arguing it was essential to write the state law into municipal code. Council President Debora Juarez also portrayed the bill as “just shoring up” city law with state law, but treatment resources were absent in the city package.

The new state law made drug possession a gross misdemeanor and stipulated up to 180 days of jail time for each of the first two offenses and 364 days on the third and subsequent offenses. Thus, King County Prosecutor Leesa Manion already has the means to prosecute drug possession, but she indicated that would not be a priority for her office given limited resources and a desire to go after more serious, violent crimes.

Davison argued her office could fill the void, but her attorneys already face heavy caseloads without the added responsibility, municipal court is already backed up, and understaffed, decrepit local jails are already nearing capacity without the added inmates. The City Attorney provided scant details about how her office would juggle resources and prioritize cases. A Seattle Council Central staff memo noted Davison provided no estimates of how many drug prosecutions she would pursue, how much each case would cost taxpayers, or any analysis of the racial and equity impacts of her proposal. Skipping committee denied an opportunity to get those answers.

Davison argued that not passing her bill would amount to legalizing drugs, which is patently false.

Seattle Police Officers can still arrest people for drug possession and seize their drugs as contraband under existing law, and Seattle municipal code already outlaws drug use in buses and bus stops. Should they so chose, police are already empowered to do an enforcement push under existing law, even if the prosecutorial discretion used by the King County Prosecutor may not be to their liking. It’s not clear Mayor Bruce Harrell and the Seattle Police Department would make carrying out minor drug arrests a priority for limited officer resources given their stated objective of going after major drug distributors and dealers (particularly of fentanyl) and perpetrators of violent crime. Officially, SPD is in favor of diverting drug users to treatment rather than defaulting to jail, as Herbold noted.

While Davison and the bill sponsors claimed to have the blessing of Manion, her predecessor Dan Satterberg – a long-time Republican County Prosecutor who switched parties in 2018 in reaction to Trump – criticized the bill.

“To me, it’s kind of back to where we were in the 80’s when we really launched the war on drugs,” Dan Satterberg told KUOW of the Davison bill ahead of the vote. Herbold cited Satterberg’s statement to close out her comments.

Nelson, Pedersen, and Davison have argued their push is different than the 1980’s offensive in the war on drugs, which was focused on crack cocaine, because fentanyl (as the strongest opiate on the market) is a new threat requiring extraordinary measures. Of course, drug war proponents made the same kinds of arguments about crack in the 80s.

While some criminal justice reformers have called for full drug decriminalization and even legalization, state leaders are not there, and lawmakers have stopped well short of that step.

Before the Washington State Supreme Court’s 2021 Blake decision, simple drug possession had been a felony, but the court ruled that the law violated constitutional due process rights by penalizing unknowing possession the same as knowing possession. Lawmakers enacted a temporary Blake fix in 2021 hoping to reform the system to focus on drug treatment rather than punishment and had originally intended to negotiate a long-term compromise during regular session this year before the temporary fix expires on July 1, 2023. However, the clock ran out before they could agree and Governor Jay Inslee opted to call a special session to pass a statewide law criminalizing drug use and offering a modest increase in drug treatment resources.

Drug overdose deaths are on the rise and spiked to 525 in King County last year. Getting drug policy right is a matter of life or death for those with substance use disorder. Jails can be incredibly destabilizing in the best of circumstances, but for opiate users jail time greatly increases the risk of overdose. Amy Sundberg noted the troubling statistics in her analysis of the bill in The Urbanist last week.

“Dr. Tom Fitzpatrick from the University of Washington School of Medicine said people who have been arrested and held in jail or prison become at increased risk of death from overdose in the time after they’re released, with one study showing the risk of death by overdose goes up tenfold in the first two weeks post-release,” Sundberg wrote. “A study done in Washington State from 1999-2003 showed former inmates were 129 times more likely to die from a drug overdose.”

“Nothing about this legislation mentions treatment programs, let along a plan to implement them,” Morales said ahead of the vote. “This feel performative.”

Morales stressed that people of color will bear the brunt of a criminalization push.

“The only conclusion that one is left to make is that this bill is not intended to solve substance use disorder. It is not intended to provide treatment to people. It is not intended – even if encouraged – to support pre-trial diversion. It is not intended to mitigate the racial disproportionality that always comes when arresting people is made easier. This sole intent is to put poor people in jail, most of whom will be Black and brown and then let them out and ensure that they have a record that follows them forever and makes it harder to get a job and to get housing.”

Whether the alternative proposal from Lewis can address these pitfalls remains to be seen.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.