American architect and urban designer Daniel Burnham’s famous “make no small plans” imperative is destroying your city and your life.

You should get a bingo card when attending a city planning conference. Instead of numbers, the squares should have pop-planning phrases to be crossed off as you hear them in lectures. Maslow’s Hierarchy and Jacob’s ‘eyes on the street’ will often get a mention. Someone using Legos to illustrate floor-area-ratio. There will be a misunderstanding of topography. Get five in a row, and you can win a ESRI tote bag.

And at the middle, the free space, should be Daniel Burnham’s “Make No Little Plans” quote. It will be the pull quote on an opening or closing slide, it’s just a matter of when.

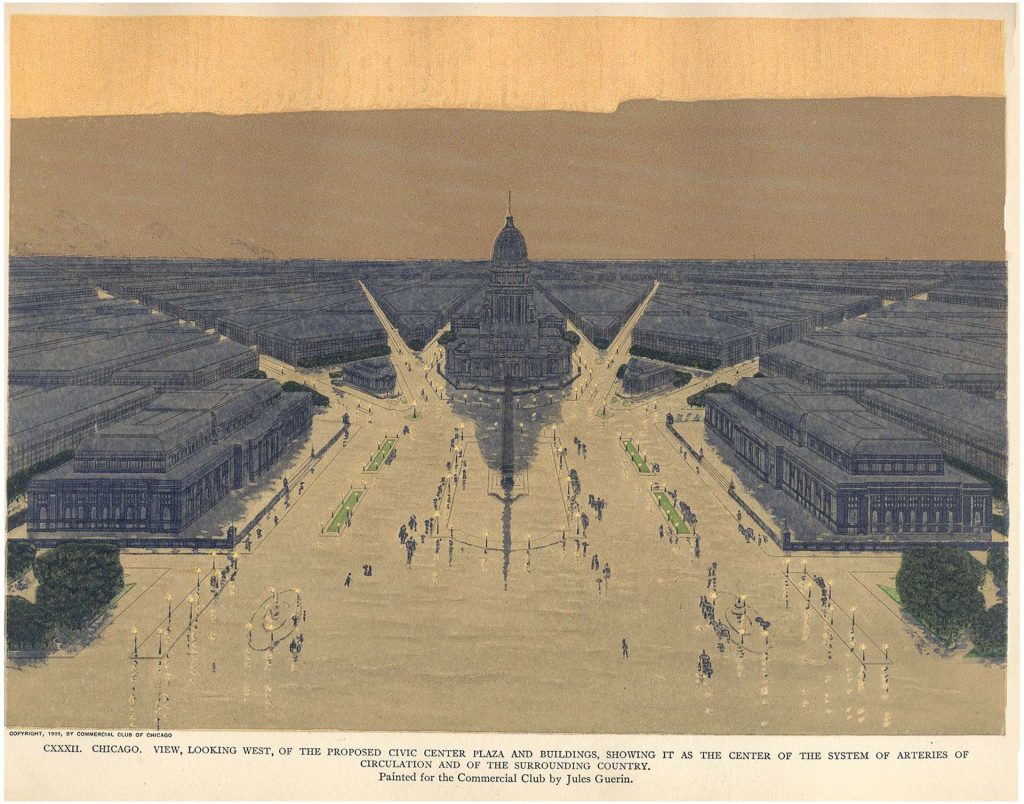

Burnham, of course, was the late 19th/early 20th-century architect that made everything pretty and electric. Pushing the Beaux-Arts movement, he used modern construction to make the big buildings, and then covered the outside with symmetrical sculptures, gold leaf, and light bulbs. The pinnacle was the White City at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, the long stretch of regal buildings that excluded non-whites and were actually just stucco. He also designed New York’s Flatiron Building and Washington D.C.’s Union Station, and accentuated anything that was stone with an archway or three at the beginning of the 20th century.

That Chicago Exposition was an attention getter, and like many big name architects, Burnham parlayed his fame into drawing an entire city. It was a maneuver that many architects take on once famous, from Le Corbusier to Frank Lloyd Wright. The architect’s career arc tends to be residence, church, coffee table book, then city plan. Burnham’s was for Chicago, with forays to St. Louis and San Francisco.

The whole quote from Burnham goes like this: “Make no little plans. They have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably will not themselves be realized. Make big plans, aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will never die, but long after we are gone will be a living thing, asserting itself with ever growing insistency.”

Unfortunately, aiming high completely detaches from the ground. What’s absolutely apparent in many of these utopian city plans is bleak emptiness. It doesn’t matter how many trees they add or how many posed humans they drop onto a sidewalk, the place is cold. And that’s because the point of the Big Plan is the Big Plan rather than the people who live there. This isn’t a place to live, it’s a machine.

At his heart, I think of Daniel Burnham as a Victorian living in America. Awe inspiring leaps of technology and the posh appearance of upper middle-classness, built on a machine greased by grinding small people to death. When one thinks of The White City, it should be discussed in the same breath as Charles Dickens. They’re flip sides of the same coin. Tiny Tim is a warning about the steam engine to which Burnham applies a pretty painted stucco facade.

The alternative to a Burnham Big Plan, naturally, should be small plans. Hundreds of little concepts that can be focused and really reflect the ideas of a specific block or community. Unfortunately, these tend to just be shoots off an original stem, together assembling into a roving bamboo forest of bureaucracy with hurdles keeping regular folks from participating in their neighborhoods.

Many of us live in places where such overplanning completely misses the daily lives of people on the ground. These are cities as coloring books, where design review boards or overwrought civic ego projects set hard lines and regular mooks like us are left to fill in the actual color and life among what’s left over. Where regular people’s lives are still allowed to occur, there’s some liveliness. Where the interactions are sparse or difficult, we have Medina.

Also, like Burnham’s quote emphasizes, the goal of Big Plans is to lock in those indelible lines and assert dead hand control long into the future. Big Plans are about remembering the design (and the designer) at the expense of the people who live there now.

The actual alternative to Burnhamism is a Little or No Plan, best summed up by Kurt Vonnegut. He said, “We are here on Earth to fart around, and don’t let anybody tell you any different.” Regardless of where we are, our living city emerges from a couple thousand people spending the day going about their lives. We meet. We eat. We work. We sleep. We fart around. It’s not that we have no plans for ourselves for the day or year. It’s that our individual plans are not based on the Big Plans of the city beyond finding a convenient way to get our morning cup of coffee. Working to dismantle barriers to that and other daily tasks should be the peak of planning and civic duty.

Such a Little or No Plan perspective is a departure from Burnham in other ways than just being more limited and human. It comes from a healthier, post-Victorian understanding of how the world works. The image of a monarch (political or architectural) controlling everything used to be projected beyond politics, from the universe to ecology to finances. Now we know that humans are the exception to seeing centralized control. Even ants and bees don’t operate by order of a queen, it’s individuals living their lives that build massive hills and hives. Big plans, like powerful queens, were a historic fluke.

Planners and architects struggle because we’re some of the few professions whose job it is to try and wrap our heads around massive, complex systems. More often than not, we get to some manageable level of that understanding. Our challenge is to resist using that understanding against people in service of our own ego.

Our job is to see those immense civic gears and make sure they’re not grinding individuals to dust. Burnham and his contemporaries simply didn’t care. They were happy to completely demolish swaths of homes, and more happy that their backwards and overbearing plans are still screwing with people’s lives. We can do so much better by simply appreciating the importance of little or no plans. Humans fart around. The best cities, and best plans, have plenty of free spaces for it.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.