The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is facing a significant shortfall in revenue from the city’s school speed zone and red light traffic cameras that will likely lead to delays to pedestrian safety and Safe Routes to Schools projects for which the funds are earmarked. Over the next two years, the program is expected to bring in $6.5 million less than originally had been anticipated, according to Seattle’s Office of Economic and Revenue Forecasts, which broke the news to a city council committee earlier this month. The City is citing a lack of sworn police officers to verify and issue tickets before the camera citations expire as a primary cause of the shortfall.

The anticipated shortfall represents nearly 25% of what had been anticipated and will likely lead to significant safety and mobility projects getting deferred. By law, 100% of the proceeds (after overhead costs) from school zone speed cameras are allocated to pedestrian projects with a nexus to making it easier for kids to walk and bike to school, along with 10% of the net revenue from red light cameras.

A number of factors are being blamed for the fact that dollars coming in are so out-of-alignment with what was projected. David Hennes, with the City Budget Office, attributed the shortfall to the fact that revenue coming from new cameras was “not as high as it had been in previous new installation situations.” In 2021 and 2022, SDOT installed the first new school zone speed cameras since 2015, at five schools across the city.

But inside the Seattle Police Department (SPD), which is in charge of verifying citations and issuing them to drivers, a prior lack of staffing is being cited as another significant reason for the shortfall. Gary Davenport, an officer in SPD’s traffic enforcement division, told the School Traffic Safety Committee that the department hadn’t been able to keep up with tickets being generated with school zone cameras being turned back on following their dormancy during the pandemic. So while the cameras captured drivers speeding in school zones, by the time SPD was able to assign someone to send them a citation, it was too late.

“As those tickets were generated, there was a time… and I don’t know the exact numbers… that many of those tickets were expiring before they were able to be processed and sent to the [driver],” he said. “There was a down time where several of those officers [where] that was their function, that was their main job every day, were in the process of either retiring or taking much of their time off, and I believe some of those tickets got away from… getting them signed off and sent to people in a timely fashion… because of not having enough officers to continually stay on top of the numbers, it got a little out of hand and some of those tickets got refused.”

Davenport asserted that recently SPD had reshuffled officers that were assigned to desk duty to working on camera tickets and that the department was back on track in sending out citations.

“At least in the last six, eight months, we haven’t had to reject any tickets because they’ve slipped away from us,” he said, noting that officers from outside the traffic division were now being assigned to work on tickets. But he also brought up the fact that it’s relatively easy to get out of paying for an automatic traffic citation, by asserting that you weren’t driving the vehicle at the time, pointing to the incredibly high numbers of unpaid citations outstanding from the lower Spokane Street bridge restrictions during the West Seattle bridge closure.

State law requires that a law enforcement officer issue the citations directly within 14 days of the traffic violation, though in recent years there has been a push to transfer responsibilities like this to civilian public employees. State lawmakers were careful to limit local authority for automated traffic cameras, with some even proposing that out-of-towners should be exempt from Seattle traffic cameras. Most traffic safety bills stalled out during this year’s session, despite a press conference early in session with Governor Jay Inslee that flirted with making them a priority as road deaths continue to trend up across the state.

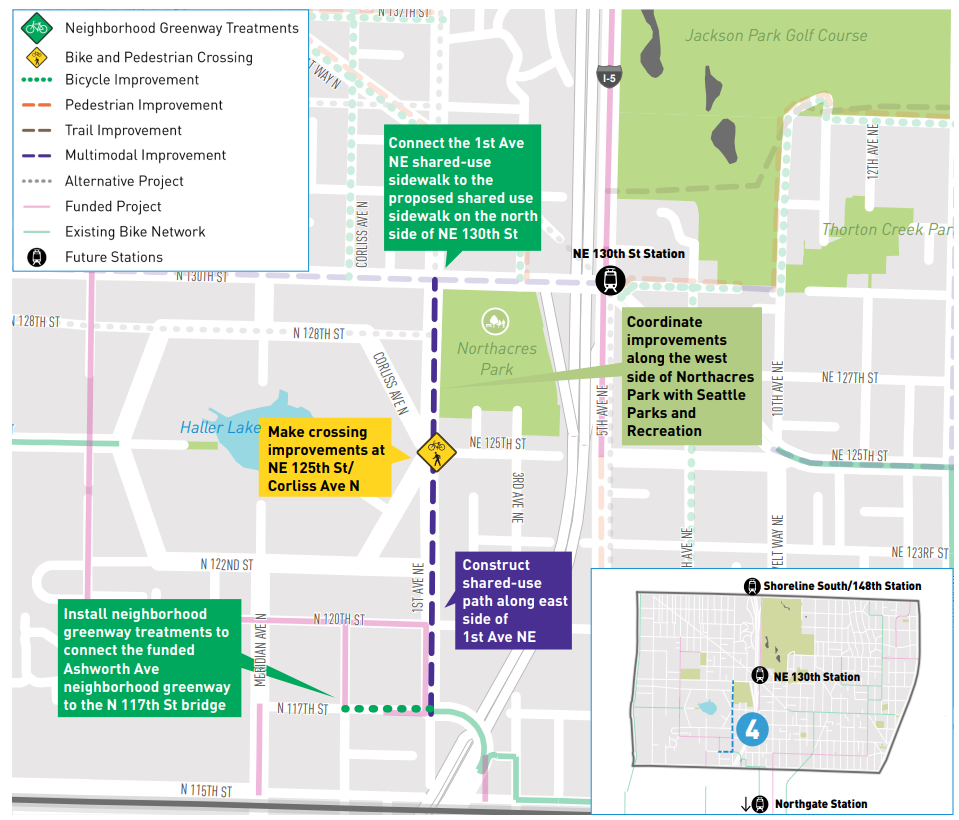

Diane Walsh, a policy specialist with SDOT, told the school traffic safety committee that the shortfall would likely mean a number of projects within the department would be delayed. She specifically cited a planned $4 million path along 1st Avenue NE between Northgate Elementary School and N 130th Street near the future light rail station on the other side of I-5. The project is part of an overall effort to improve access to that isolated station, aided by a federal grant, and she said it was set to be delayed by two years due to the shortfall. It’s now unclear whether the path will open by the time the light rail station opens in 2026.

But Walsh stressed that things were very much still up-in-the-air. “I don’t think there’s a clear path right now, it’s just easier to delay some of those projects that are using a substantial amount of funding,” she said.

“I think we should take this as a lesson that using tickets to fund the majority of our pedestrian project budget… it doesn’t make a lot of sense,” Mary Ellen Russell, a member of the school traffic safety committee, told The Urbanist. “If pedestrian projects are a priority, then they should be funded like a priority, with the same sorts of stable funding that other projects get. Even if this mistake had not happened, tickets decline over time as user behavior changes, so we can’t plan to fund our pedestrian projects with ticket revenue.”

But by law, school zone cameras can only fund pedestrian projects, so if there are funding shortfalls, those are the projects that take the hit.

Russell thinks the department should be able to backfill the funding from elsewhere. “From my perspective, it’s obvious that money should be shifted from other programs, because in terms of SDOT’s budget it’s a very small amount of money,” she said.

SDOT’s press secretary Ethan Bergerson told The Urbanist that the department is looking at all options that could be on the table.

“The Safe Routes to School program continues to be a very high priority for SDOT. We are currently working to understand the impact of this funding adjustment and identify options to minimize the impact to the Safe Routes to School program,” Bergerson said.

The city is set to dramatically increase the number of school zone cameras on top of the new ones that have gone in recently, thanks to a amendment proposed by Councilmember Alex Pedersen in last year’s budget. SDOT is wrapping up an analysis of the equity impacts of where those cameras could be installed before they can move forward. For those new cameras, the city took an extremely conservative approach to expected new revenue, anticipating only $1 million per year in new money even as the number of total school zone cameras is expected to double from 35 to 70.

But with that many new cameras, it remains to be seen whether the Seattle Police Department will be able to keep up with a potential flood of new tickets to process, allowing the city to fully capture that revenue to fund badly-needed pedestrian projects.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.