Seeking to grow its tree canopy cover, Seattle — a city originally built on logging and carved out of towering old growth forest — has now made it more costly and challenging to cut down a tree. The Seattle City Council voted 6 to 1 yesterday to pass legislation establishing new tree protections. Councilmember Alex Pedersen was the lone vote against the bill and had already made his dissatisfaction well known with a barrage of amendments in committee which his colleagues roundly rejected.

Behind the scenes, backers had worried the bill’s outcome was in doubt after The Seattle Times editorial board came out hard against the proposal on Friday with an editorial that was riddled with misleading information titled “Seattle’s proposed tree ordinance is the legislative equivalent of a chain saw.” That sensationalist take helped whip up a late surge in comments against the bill, but ultimately did not forestall the outcome.

Councilmember Dan Strauss chairs the land use committee and sponsored the ordinance. He led the charge in rejecting Pedersen’s amendments, noting they seemed focused on blocking housing rather than protecting trees. Strauss argued the ordinance struck the right balance between meeting housing needs and tree canopy goals. The City has an official goal of at least 30% tree canopy cover, but is falling short of that now.

“When I first took office, one of my top priorities was to pass new, stronger legislation to protect Seattle’s trees,” Strauss said in a statement. “My aim was to pass a balanced bill that protects trees in our neighborhoods and during development while making space for the housing our city – the fastest growing city in the nation – desperately needs. This Tree Protection Bill protects the canopy we have today and grows the canopy my grandchildren will benefit from.”

The new ordinance restricts the size and frequency of tree removals by property owners and imposes a requirement on developers to replace trees 1:1 or pay an in-lieu fee that rises with the diameter of the tree. Those fees are then pooled into a fund to replace trees, with the most canopy-starved areas prioritized. Many of these tree-barren areas are in South Seattle and in and around Seattle’s industrial zones, so the law hopes to promote environmental justice and more equitably spread canopy as it adds trees.

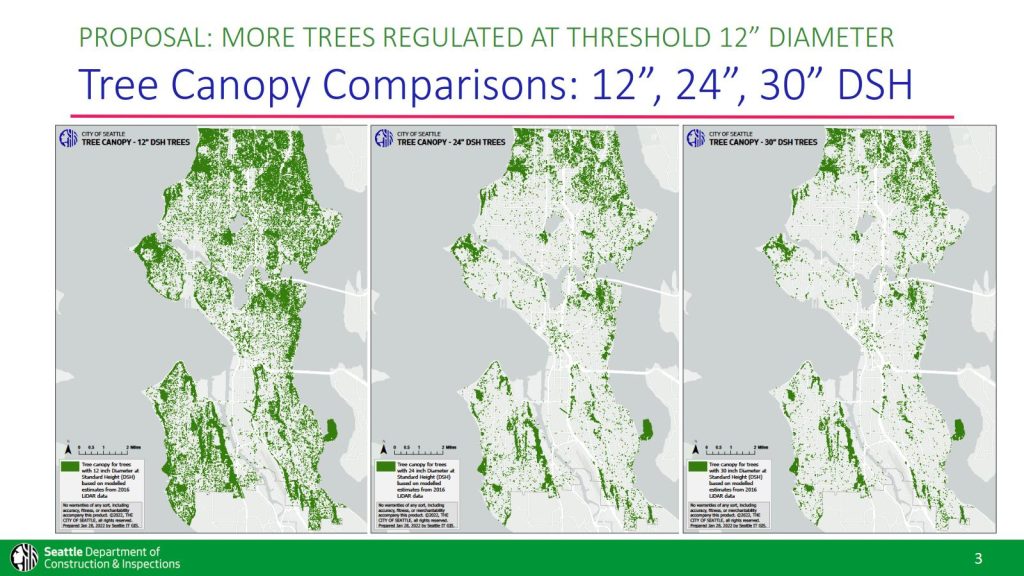

In effect, the ordinance expands protections to a total of 175,000 trees across the City, whereas the previous code only protected approximately 17,700 trees, according to Council staff. Previous tree removal restrictions applied only to “exceptional” trees and large trees exceeding 30 inches in diameter.

In an op-ed in The Urbanist, architect David Neiman opined that the new regulations would add to the city’s housing woes, creating new hurdles to homebuilding as tree removal fees and paperwork gobble into profit margins and render some projects infeasible. In stark contrast to the aforementioned paranoid Seattle Times editorial, Neiman noted the ordinance expands regulatory oversight of trees rather than diminishing it: “Every tree larger than six inches in diameter will now be subject to new regulations.”

While some developers remained skeptical, the largest voice of the development community, the Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish Counties (MBAKS), ultimately supported the bill and celebrated its passage, as did the largest voice of nonprofit builders, the Housing Development Consortium.

“This process recognized the importance of both housing and trees,” said MBAKS executive director Jerry Hall. “Seattle struck a thoughtful balance to preserve tree canopy while creating a pathway for more housing.”

Jesse Simpson, who is policy manager at Housing Development Consortium of Seattle-King County (and a boardmember at The Urbanist) agreed with that assessment in a statement on behalf of the coalition of affordable housing builders and professionals.

“The Housing Development Consortium believes the updated tree ordinance strikes a delicate and appropriate balance between expanding tree protections and ensuring these regulations do not impede desperately needed housing production,” Simpson said. “Non-profit housing developers need predictable and flexible standards to construct affordable housing at the pace called for by our ongoing housing crisis. We think the revised tree code will help grow our city’s tree canopy while allowing our members to build the homes needed to make Seattle a more affordable, equitable, and inclusive city.”

Echoing that theme of predictability and balance, MBAKS Government Affairs Manager Aliesha Ruiz emphasized the housing lens in an Urbanist op-ed. On Tuesday, she concluded the bill had effectively incorporated this lens and provided developers with greater certainty in the permitting process. Previously, homebuilders complained they lacked certainty, until late in the process, about which trees they were allowed to remove from a building site and which they were not.

“The result is an improvement over the prior tree code which invited a great degree of interpretation, causing unpredictability that proved to be a costly barrier to new housing construction,” Ruiz said in a release Tuesday. “By building predictability into the new code, Seattle is empowering builders and homeowners to be part of the solution to our housing crisis.”

A recent analysis of housing needs projected the City of Seattle will need 112,000 new homes over the next 20 years.

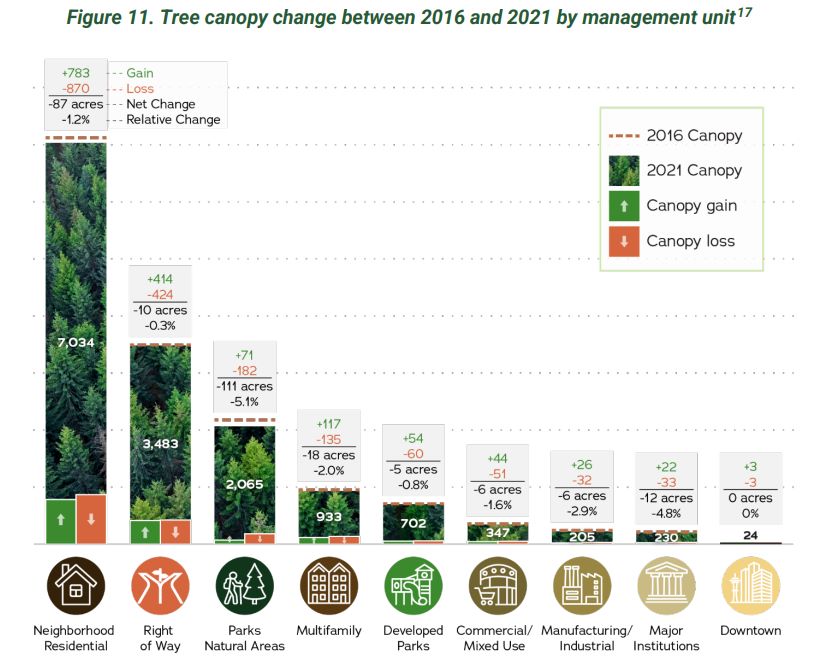

Likewise, the City’s recent study of tree canopy also raised alarms as it found tree cover had shrunk by 255 acres between 2016 and 2021, dropping from 28.6% to 28.1% citywide, a drop which was largely attributed to climate change. Much of that loss occurred on public land, such as street right-of-ways, parks, and greenbelts, but the new tree ordinance seeks to stem losses and rebound tree cover on private land. The city’s Neighborhood Residential zones saw the second largest net loss at 87 acres and were largely unregulated previously, with the old code more focused on denser multifamily zones.

The need to expand trees protections in Neighborhood Residential areas makes the opposition from Pedersen and the Seattle Times all the more odd and contradictory. Several councilmembers noted that they should not let the perfect policy be the enemy of the good, and yet some still claim to see the policy as a “chainsaw” rather than an expansion of tree protections. The Seattle Times‘ sordid record on housing policy suggests blocking homes might be part of their motivation.

Unlike the opportunistic environmentalists at the Seattle Times, Sierra Club Seattle joined the chorus in support of the legislation.

“One of the most important things we can do as a city to tackle the climate crisis is to have a healthy urban forest and provide urban housing at the same time, since both reduce carbon emissions,” said Chair Robert Cruickshank in a statement. “We’re excited to celebrate Mayor Harrell and Councilmember Strauss successfully passing these reforms to provide that policy harmony for our environment and our future.”

The Urbanist’s Ray Dubicki, meanwhile, opined that the City of Seattle should apply these new tree regulations to itself and focus on adding tree cover on public lands, such as by lining more streets with canopy-providing trees or tearing up parking strips for tree-rich pocket parks.

The biggest barriers to continuous tree canopy are the city’s streets, and Seattle’s city council has complete control over those. If a tree is important enough to alter development of a house, it’s important enough to alter the parking space in front of that house. The council can use the new ordinance to show its leadership.

Instead of relying on postage stamp yards preserving trees here and there, the city can truly expand the tree canopy by connecting parks and neighborhoods with redesigned parkways. Take the city’s immense arterials and replace parking and travel lanes to create broad boulevards of real, continuous green coverage. Less asphalt, more foliage. The Olmstead Brothers proposed it a century ago. We do it on a couple select streets already, like the 14th Avenue Gemenskap Park in Ballard, Ravenna Boulevard, and 17th Avenue north of UW. A real tree ordnance would be the blueprint for more, distributed equitably through the city. Otherwise, the new tree legislation is just shifting the onus to homeowners or sticking a few more lollipop plastic trees in a cloud of exhaust.

Ray Dubicki

Mayor Bruce Harrell alluded to the need to add trees on public land in his statement on the bill’s passage.

“This legislation takes a One Seattle approach to balance prioritizing tree canopy while also allowing for development of needed housing – crucial for progress on climate goals, homelessness efforts, and housing affordability,” Harrell said. “Combined with our recent Executive Order that takes action to equitably grow tree canopy on public land like parks and natural areas – which saw the greatest net losses in canopy coverage according to the 2021 Tree Canopy Assessment – the City is doing more than ever to protect, maintain, and grow our urban forests and ensure neighborhoods with the lowest canopy coverage see the most support.”

It remains to be seen if in-lieu fees from developers will provide sufficient funding for the City’s tree planting efforts or if the City will need to top up funding from its own coffers.

Polling has indicated strong support for tree protections and expanding canopy; likewise, support for expanding housing in all Seattle neighborhoods is similarly strong. Chair Strauss believes his policy has threaded that needle and achieved both aims. Strauss also pledged to iterate and continue to finetune the policy as necessary, which helped win over a few hesitant votes like Councilmember Lisa Herbold.

Time will tell if steady growth in both canopy and housing can be achieved with the new ordinance.

The Seattle City Council provided the following summary of the legislation:

- “Expands protections to a total of 175,000 trees across the City; the previous code only protected approximately 17,700 trees.

- Creates a four-tier system to categorize our city’s trees and designate different protections for each tier. Heritage trees are tier 1 and removal is prohibited unless the tree is hazardous. This tiered system also expands the definition of ‘exceptional’ trees so that 24″ trees are included; the previous requirement was 30″.

- Establishes a new mandate requiring new developments to include street trees in their plans, helping to increase the overall tree canopy in our city while improving the quality of our urban environment.

- Increases penalties for illegal street cutting.

- Expands Seattle Public Utilities (SPU)’s Trees for Neighborhoods Program that has already helped Seattleites plant over 13,400 trees in their yards and along the street.

- Creates additional penalties for unregistered tree service providers performing commercial tree work, such as loss of a business license or significant fines.

- Replaces trees onsite if they’re removed for development or requires a fee be paid to plant and maintain trees in under-treed areas.

- Increases street tree requirements for developments in neighborhood residential zones.

- Addresses the lack of trees in historically underserved communities through the establishment of a payment in-lieu program that will help fund tree planting and maintenance programs around the city.

- Significantly restricts tree removals on Neighborhood Residential lots:

- Near absolute restriction on the removal of Tier 1 (Heritage) Trees.

- Restricts the removal of all Tier 2 trees. Removal of a Tier 2 tree for any reason other than construction or safety is now prohibited.

- Lowers the size threshold for Tier 2 (currently Significant 12”–30”) trees from 30” to 24”.

- Lowers the number of Tier 3 (formerly Significant 6”) that can be removed from original draft-Limit of 2 trees that can be removed to two trees every three years.”

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.