Twenty degrees.

That’s how much higher temperatures in Seattle were during a heatwave this week compared to what we usually experience this time of year, according to the National Weather Service (NWS).

The increased frequency, duration, and intensity of heatwaves are indicators of climate change – the result of human activities like carbon pollution.

Historically, Seattle’s maritime climate delivered spring weather that was reliably overcast with cool temperatures and rain, earning names like “May Gray” and “June Gloom,” mid-May this year was oddly sunny and alarmingly warm.

On the heels of back-to-back summer heatwaves, The Urbanist compiled the following explainer to put this unseasonal weather event into context.

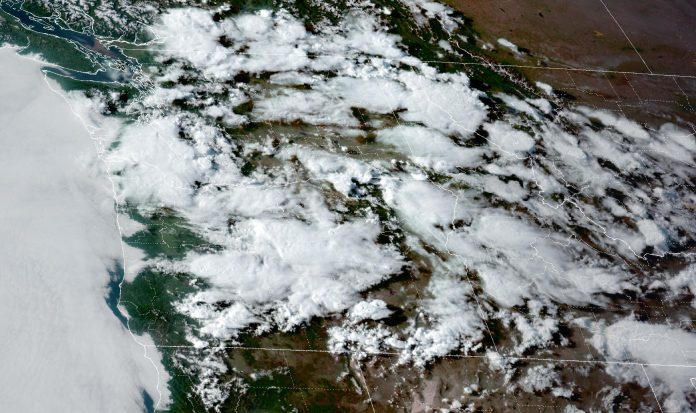

The heat came with a high-pressure system

In a jet stream, narrow bands of strong wind flow from west to east in an arc-like shape. As air moves down along a curve, it sinks and becomes warmer.

“We had a really strong ridge of what we call a ridge of high pressure,” said lead forecaster, Trent Davis, with NWS in Seattle.

“These events tend to lead to heat events because we have more daytime heating from the sun, and that leads to sinking areas and suppresses cloud formations, and so that’s why we have so many days of really sunny skies. The long days perpetuate day after day,” he said.

The summer-like temperatures began to build last week with three days in the 70s followed by two days in the 80s. Sea-Tac Airport recorded the peak, a record high of 89 degrees, on Sunday. Warm days will persist through Friday.

Along with the hot temperatures comes the potential for thunderstorms. It’s rare for the Seattle area to get thunder and lightning, because the region’s typically cooler air hinders the moisture needed for storms. Between Monday night and Tuesday morning this week, NWS counted 1,300 lightning strikes.

“The ridge is breaking down a little bit,” said Davis. “It’s cooler air, in a relative sense, but it’s still pretty warm at the surface. That’s bringing cloud cover and more moisture. It’s leading to some really good instability for fuel for thunderstorms.”

Rain falls swiftly and intensely from these kinds of storms. That’s because the clouds hold the moisture and release heavy rain like a sponge being wrung out. It prompted NWS to issue a flood watch on Monday.

Davis and his team were particularly concerned about towns in King County like Skykomish, where people now live near land scorched by last year’s Bolt Creek Fire. That wildfire burned so hot, what remains is earth that can’t absorb water. Instead, rain runs off and creates flash flooding.

Climate change made an early heatwave more likely

While meteorologists monitor the behavior and conditions of the atmosphere over a short period of time, climatologists measure it for much longer, usually with data collected over 30 years. Even with firm methodologies to identify trends, determining if one weather event is caused by climate change is difficult.

“It could be happenstance, and it’s an unusual weather event, but one thing that gives me pause though, is it’s a rather long duration, as well as above normal temperatures in the Pacific Northwest,” said Washington State Climatologist Nick Bond.

Climate Central, a policy-neutral nonprofit, uses a Climate Shift Index to indicate how much climate change has altered the frequency of today’s temperatures. Based on this scale, climate change made Seattle’s excessive heat this May five times more likely compared to spring days decades ago.

Additionally, Seattle’s historical records show evenings are not cooling off like they used to, and the frequency of evening heatwaves is increasing. It’s reflective of what is happening across the country: Summertime temperatures are arriving earlier and lasting longer.

“We generally do not get heatwaves this early in the season,” Bond said. “One of the things we are seeing with climate change in general is the lengthening of the window in which heat events can happen. This [heatwave] is an example of that.”

Unseasonal spring temperatures could affect what happens this summer

This spring reminds Bond of the dry and warm spring of June 2021 – a year that had a challenging wildfire season and disastrous summer heatwave.

Wildfire is a natural process for forests and wildland areas, but with climate change they are burning hotter and lasting longer. While wildfire used to be considered an Eastern Washington issue, smokey summers are a new normal in the Seattle metro area.

“[The heatwave] is definitely something we’re taking seriously,” said Thomas Kyle-Milward, wildfire communications manager for Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR). “Thanks to snowpack, fuels are still in good condition. We aren’t at the stage of deploying resources yet, but we are keeping a really close eye on this because it’s unseasonal temperatures that will accelerate the drying out of fuels.”

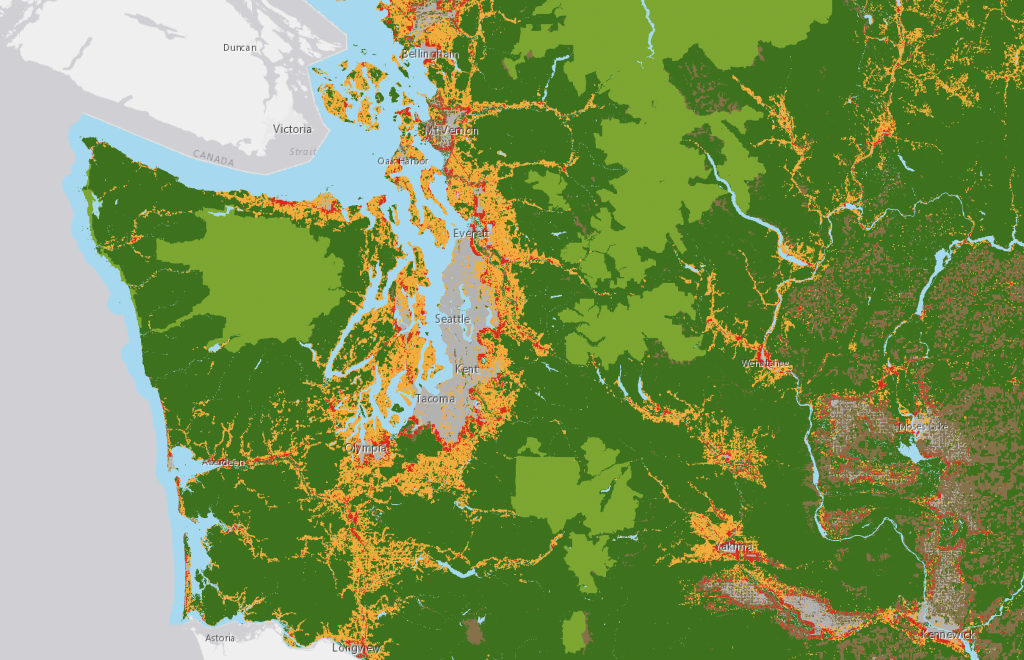

Before the heatwave, DNR also announced that cities in South Puget Sound and eastern King County are considered high risk for fire. Also, the National Interagency Fire Center predicted significant wildland fire potential this summer.

Meteorologists can’t predict this far in advance if Seattle will have another heatwave this summer. Temperature outlooks for June and July could be warm, like earlier this May. Precipitation could also be below normal, according to the Climate Prediction Center.

Seattle’s built environment makes its people vulnerable

Seattle is a city that struggles in heatwaves because its infrastructure and built environments were designed for a cooler, temperate climate. The extremely hot days, especially when temperatures don’t drop at night, stresses equipment that is part of essential services like Seattle City’s Lights distribution system. Also, Seattle is among the least air-conditioned metro areas in the U.S.

For those without cooled homes, residents may be sensitive to heat. It’s especially severe early in the year when people haven’t had time to acclimate after rainy and cold winters. The exposure may trigger illness like heat stroke and exhaustion.

King County and the City of Seattle responded to this week’s weather, citing a lower heat index compared to recent summer heatwaves. People without shelter are among the most vulnerable to heat, and the King County Regional Homelessness Authority opened day centers with cooling and distributed supplies like water. King County Metro is also allowing people to ride buses as a cooling center.

While in the thick of summer heatwaves, cooling centers are challenging for some neighborhoods to get to because they are not walkable locations or near public transit.

This includes people in South Seattle and King County, where some of the most racially and ethnically diverse populations in the region live. Residents in these areas experience the heat and its risks inequitably because of limited greenspace, reduced tree canopies, and greater prevalence of pavement. Hard pavement absorbs more solar radiation than natural land cover. Not only does it increase heat-related illness, but it exacerbates pollution levels.

Since 2021’s deadly heatwave, the City of Seattle and King County made some tactical improvements in their emergency response to better protect people who experience the worst from extreme — and often disproportionate — heat. But as The Urbanist reported last summer, Seattle is decades away from the heat mitigation it needs to keep all residents safe.

Ashli Blow

Ashli Blow is a Seattle-based freelance writer who talks with people — in places from urban watersheds to remote wildernesses — about the environment around them. She’s been working in journalism and strategic communications for nearly 10 years and is a graduate student at the University of Washington, studying climate policy.