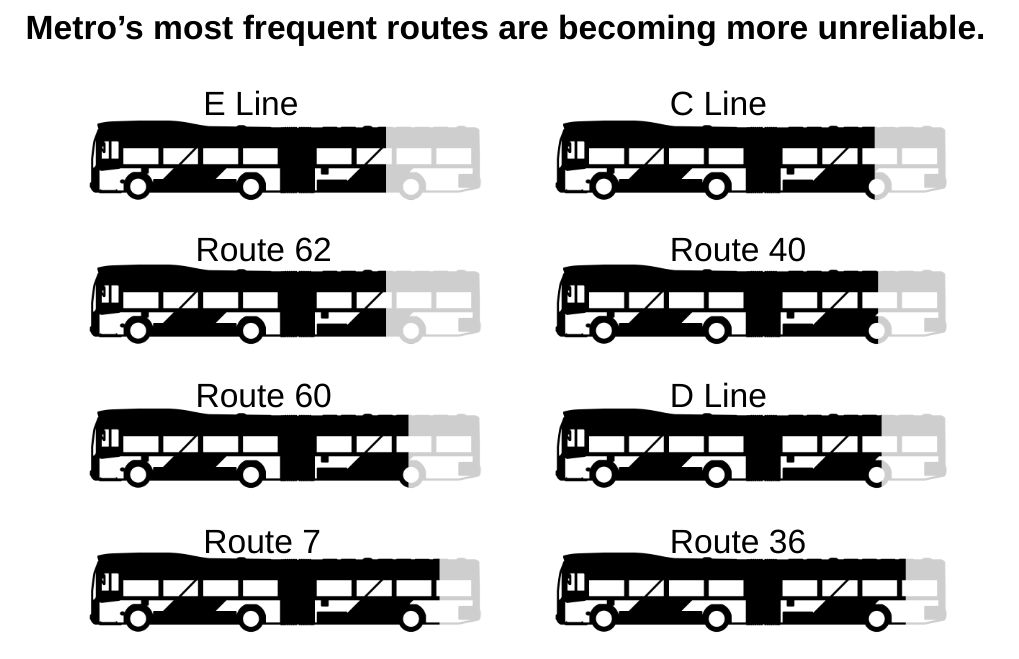

King County Metro will significantly scale back the number of scheduled bus trips across the county this September, impacting 4% of trips across the entire system, the transit agency announced on Thursday. First reported by The Seattle Times, the changes to schedules are intended to better reflect what Metro can actually provide, and will impact peak-only bus routes the most. However, some of Metro’s most frequent routes will also see reductions.

A shortage of operators and bus mechanics and supply chain issues have been impacting the ability to repair buses are the primary culprits the agency pointed to in its announcement.

Peak-only Routes 15, 16, 18, 29, 55, 64, 114, 121, 167, 190, 214, 216, 217, 232, 237, 268, 301, 304, 320, and 342 will be officially suspended as of September 3, indefinitely. Many of these 20 routes see a fairly significant portion of their trips cancelled right now, but cancellations are also spread out over other routes. The peak-only routes have been much slower to regain ridership.

Katie Chalmers, Metro’s Managing Director of Service Development, explained that these routes were selected because of those ridership numbers and their overall equity scores that take into account what geographic area of the county they serve, and what replacement service is available nearby.

Meanwhile, Routes 7, 10, 20, 28, 36, 73, 79, 225, 230, 231, 255, 345 — some of the agency’s most high-ridership routes — will see trips removed from their schedules to give riders a more accurate picture of arrival times across the system.

“Today’s conversation is a challenging one for us, because it’s not what we want to do. We want to be in a growth pattern,” Metro General Manager Michelle Allison said Thursday. “But we also recognize over the past couple months, listening to our employees, and listening to our riders, that we have to stabilize the system and provide reliable service, so we can then build on top of it to get to that larger Metro Connects [long-range] vision.”

Allison told reporters this week that the agency is currently having to cancel 3% of trips systemwide due to operator availability, and emphasized that the changes planned for September aren’t an actual reduction in service but a recalibration of scheduled trips to better reflect reality. Metro went through a similar recalibration last fall, similarly scaling back scheduled trips on a broad number of routes. The Urbanist warned those fall service cuts should “raise alarm bells” for policymakers warning of the need to tackle the operator shortage. That has yet to happen, but nonetheless, by March, the agency had believed it was ready to enter a growth period again, which turned out to be too optimistic.

“We were really hopeful that we would get the workforce and supply chain issues to even out, and to be at a more steady state than folks are experiencing. So we kept service on the street in the hope that return-to-work would manifest in a big way and we would have the service there to meet those ridership needs. And that didn’t happen,” Allison said. “We were hopeful, and we had a lot of service out there to meet the needs of recovery, and they simply didn’t result.”

While the labor market is tight, both industry-wide and service sector-wide, other agencies have not struggled as mightily as Metro. In contrast, LA Metro just announced it had hired 1,000 transit operators, allowing it to fully restore service to pre-pandemic levels. In a post Monday, the agency laid out its successful strategy, which included a union contract that raised pay and allowed the agency to hire new operators at full-time hours rather than requiring that they start at part-time. King County Metro faces similar obstacles in recruiting, still unaddressed.

Allison said that Metro will do its best to communicate on a week-to-week basis which routes it won’t be able to deliver between now and September, but that it would still remain “clunky” for some riders.

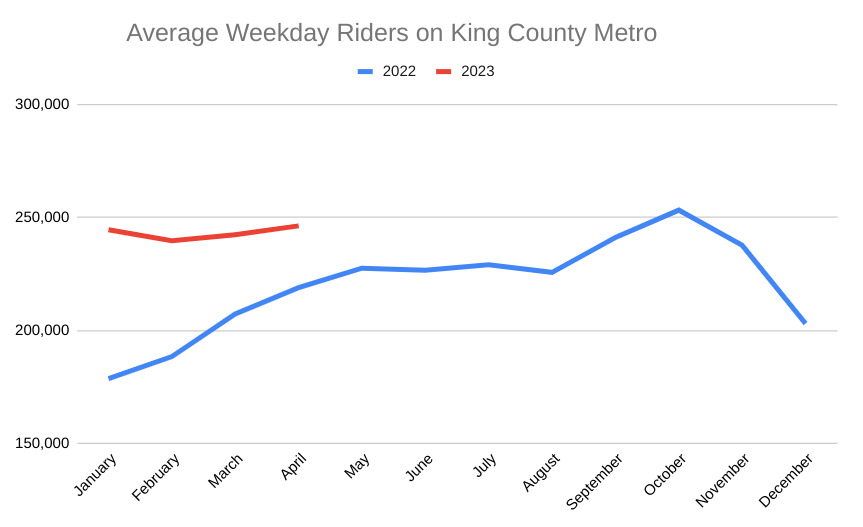

That clunky system is not likely to bring people back to the system. Metro has continued to regain ridership month-over-month, but overall weekday ridership remains in the same general window of around 200,000 to 250,000 trips made per weekday on average, around 40% below pre-pandemic levels. The agency averaged more than 400,000 daily weekday boardings pre-pandemic.

As for high ridership routes like the 36 and the 7 being on the chopping block, Chalmers defended the decision to cancel trips with the fact that overall frequencies would still remain relatively high.

“Those two routes will continue to see very frequent service, but we will be taking some trips out, particularly out of the peak periods, so rather than operating every six or seven minutes, they’re going to operate every eight to ten minutes in certain times,” Chalmers said. “Our goal is to offer that reliable service that meets demand, and we can still provide customers on those routes with that very frequent service.”

Metro’s inability to recruit and onboard new bus operators has plagued the agency for years now, with operator pay, benefits, and work environment all playing a role in sluggish hiring. Metro operators, as part of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 587, have been operating without a contract since last fall. But the King County Council, which will ultimately be tasked with fixing the hiring crisis, has been slow to provide concrete solutions while those contract negotiations are ongoing.

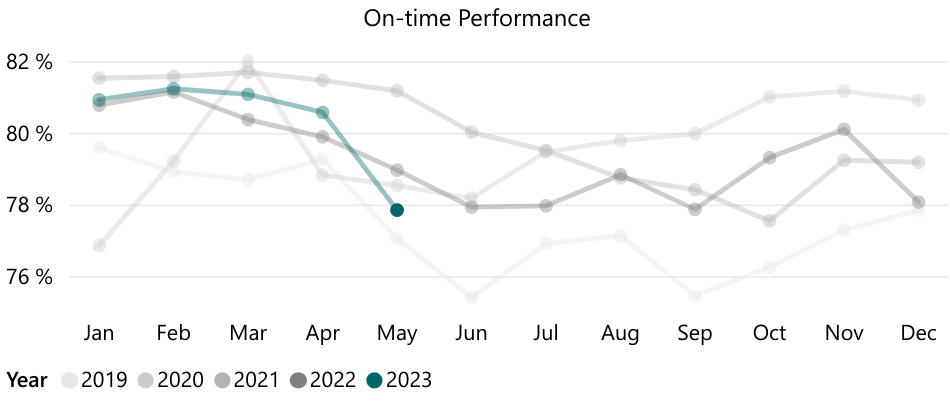

Struggles to restore service come at a time when demand for transit would be expected to increase, as more companies in and around Downtown Seattle tighten up their work-from-home policies, a change that city government has largely embraced. On May 1, Amazon put in place a requirement that workers be in the office three days a week in many instances, and the impact on traffic has been noticeable. Initial data suggests that this is also having an impact on transit reliability, with overall on-time performance dropping over 2% just between April and May so far to date.

The fact that public transit is not able to act nimbly right now will undoubtedly have an impact on the city’s downtown recovery plan. Disruptions on Link light rail and bus trip cancellations and delays are something riders have come to expect. Downtown Seattle can’t really function if everyone drives there, and buses caught in traffic add to that feedback loop.

Jamie Housen, director of communications for Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell, told The Urbanist that the administration was continuing to prioritize transit.

“Mayor Harrell believes restoring transit ridership must remain a key priority of a comprehensive and equitable pandemic recovery, including for downtown,” Housen said. “The City of Seattle remains a committed partner with King County Metro in keeping Seattle moving and encouraging more trips on transit, as well as ensuring transit is welcoming and rides are safe.”

Housen pointed to the northbound bus lane on Rainier Avenue that the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) added last year, and projects like Route 40, Route 44, and RapidRide G Line as evidence that the administration is prioritizing transit, but many of those projects won’t show benefits to riders for several more years. Later this year, SDOT will extend the 3rd Avenue bus mall three additional blocks to Blanchard Street in Belltown, which will likely provide a small gain to service reliability, but quick-build transit reliability projects are mostly few and far between, with a lot of process required to get buses moving. A bus spending even more time stuck in traffic is one that likely leads to a cancelled trip elsewhere.

Spending less on wages due to the labor shortage, Metro has money in the bank. When asked what that money would be invested in to help riders, Allison pointed to security and cleaning, which were prioritized in the last County budget, rather than bus lanes, bus stop improvements, or transit signal priority, which could speed trips and increase reliability. Metro already has a priority list of such projects, which would take collaboration with local departments of transportation to implement, but could pay dividends if prioritized. The recent Commute Seattle survey indicated service reliability, frequency, and convenience were the biggest things holding back transit ridership, well ahead of safety concerns.

There really isn’t a silver lining to Metro’s announcement this week, with riders still tasked with negotiating an unreliable system until September and no signs for improvement on the horizon. But ideally, the announcement will be a wake up call that inspires renewed interest in getting Metro back on the path to success.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.