Not allowing drivers to make a free right turn at a red light, or a left turn from a one-way street, will be the default setting for any new or modified traffic signal, according to a memo signed by leadership within the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) in early March. The memo requires a determination for any deviation from the no-right-on-red policy and outlines a clear justification for the policy around safety. The policy change comes on the heels of the “top to bottom” review of the Vision Zero program, which recommended restricting right-on-red among other safety interventions.

The change doesn’t mean that right-on-red will be restricted every single intersection in Seattle anytime soon, but rather that every time a project within the department deals with replacing or modifying a traffic signal, SDOT will have to find a reason justifying not to add “no turn on red” signage. “Prior to design, the operations team will review potential locations to determine if an exception from this general policy is recommended,” the memo states. “Vehicular delay will not generally be considered unless necessary for coordination with partner agencies.”

“The general guideline for this evaluation will be to add No Turn on Red restrictions unless there is a significant operational reason not to,” the department wrote in a blog post released today. “At some intersections, it may not be feasible to install a No Turn on Red sign until additional mitigation can be completed, such as signal timing adjustments.”

The memo cites a recent study, published in the journal of the Institute of Traffic Engineers (ITE), looking at Washington, D.C.’s implementation of no-turn-on-red restrictions at 100 intersections in 2019. Driver-to-driver conflicts were reduced by 97%, and vehicle-pedestrian conflicts were reduced by 92% following the installation of consistent no-turn-on-red (NTOR) signage. “The outcomes of this study indicate potentially positive effects of NTOR restrictions that can serve as a basis for developing a standardized methodology that considers both peak and off-peak vehicle and pedestrian demands,” the ITE journal notes. “These improvements came at overall minor impacts to traffic operations. These findings have helped the District identify a low-cost safety tool that will help in its pursuit of Vision Zero.”

But the study also noted a 30% increase in crosswalk encroachment by drivers following the deployment of the broad signage, as drivers started their turns but didn’t complete them.

The new policy will not apply when the city does routine maintenance, or when it modifies signals to add Accessible Pedestrian Signals (APS), which provide low-vision people auditory clues that it’s safe to cross the street. The rule will also not apply when signal timing is the only thing about a signal that is modified.

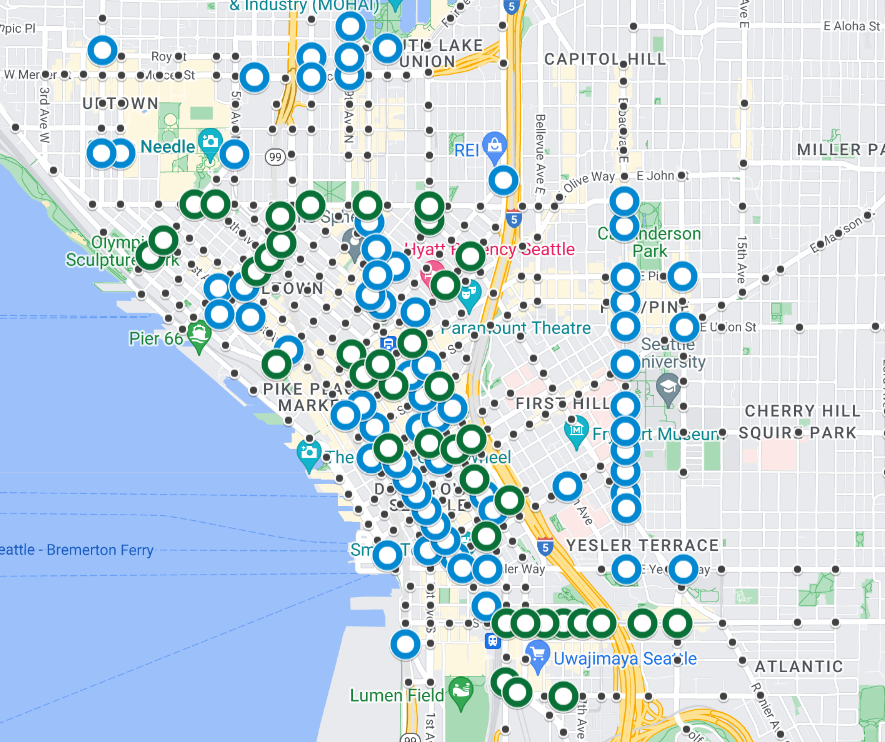

Following the release of the “top of bottom” Vision Zero review in February, which included a recommendation to expand right-on-red restrictions by this July when Seattle hosts the Major League Baseball All-Star Game and the city will see a considerable increase in foot traffic downtown, SDOT crews have already started adding new signage. SDOT Director Greg Spotts, on a field visit in mid-April, highlighted new no-turn-on-red signage in Denny Triangle and linked to a map showing where signage is currently planned to be added by the end of 2023. Only a few of the planned signs (in green) are set to be added in areas outside of central downtown.

By the end of this year, SDOT expects to go from about 100 intersections where turn-on-red had been restricted to close to 150, a big relative increase but still just a fraction of the over 1,000 signalized intersections that SDOT maintains citywide. The city has also announced deployment of no-turn-on-red along Aurora Avenue as an interim spot improvement as the city designs potential longer-term improvements for the corridor, adding right turn restrictions to its list of immediate safety interventions.

But wider deployment of turn restrictions outside of downtown still remains to be announced. “As part of our commitment to Vision Zero, we will continue to evaluate and install ‘No Turn on Red’ signs in other pedestrian dense neighborhoods throughout the city over the next year,” today’s announcement notes.

Seattle’s move follows a push at the state level to force municipalities to broadly apply turn-on-red restrictions in the name of improving pedestrian safety. A pair of twin bills introduced in the Washington House and Senate, HB 1582 and SB 5514, would have required cities to install no-turn-on-red signage within 1,000 feet of a school, park, library, childcare center, hospital, senior center, public transit center, or any “other facility with high levels of pedestrian traffic determined by the appropriate local jurisdiction.”

That push didn’t gain traction among lawmakers, with neither bill moving beyond an initial public hearing in 2023. That isn’t incredibly surprising given that the proposal hadn’t really been circulating in the legislature before this year and the fact that neither bill included any local funding for cities to install signage at thousands of locations across the state, a big hurdle for any policy change to be able to overcome local opposition.

Outside Seattle, right-turn-on-red shows signs of becoming another polarized partisan issue. In April, an Indianapolis city council committee approved a proposal to restrict turn-on-red at 190 intersections just in that city’s commercial core, with the four Republicans on that committee voting against the proposal but being greatly outnumbered by support from committee Democrats. Days later, Aaron Freeman, a Republican state senator in the Indiana General Assembly, succeeded in getting an amendment added to unrelated bill that would prevent Indianapolis from restricting turn-on-red anywhere within the city. The data illustrating significant safety gains have apparently not been enough to win over Republicans in Indiana.

No-turn-on-red restrictions are as close to a consensus issue as you’ll find in the city of Seattle, however, and the Seattle Department of Transportation’s move to make them the default with all modified signals suggests that SDOT is ready to go all-in on making them a permanent and widely deployed fixture of the city’s streetscapes.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.