What is the value of the row of trees that sit along your street?

Cities in Washington are working to give those trees more importance in their planning considerations, centering urban forestry in their community strategies. With the housing crisis and mounting pressure of climate change, city governments are balancing the need for development and safeguarding their urban natural resources.

Statewide missing middle housing reform (HB1110) passed this legislative session and ignited discussions surrounding multifamily housing, upzoning, and urban growth areas that revolve around sustainability, housing opportunity and affordability. They also intersect on the question of urban forestry and tree canopy.

“From a sustainability perspective, encouraging growth in dense areas like Seattle is a clear and definitive positive for our region,” said Brennon Staley, Strategic Advisor for the Seattle’s Office and Planning and Community Development.

Staley said development in dense places like Seattle prevents further sprawl on the fringes, preserving more land and natural resources from development.

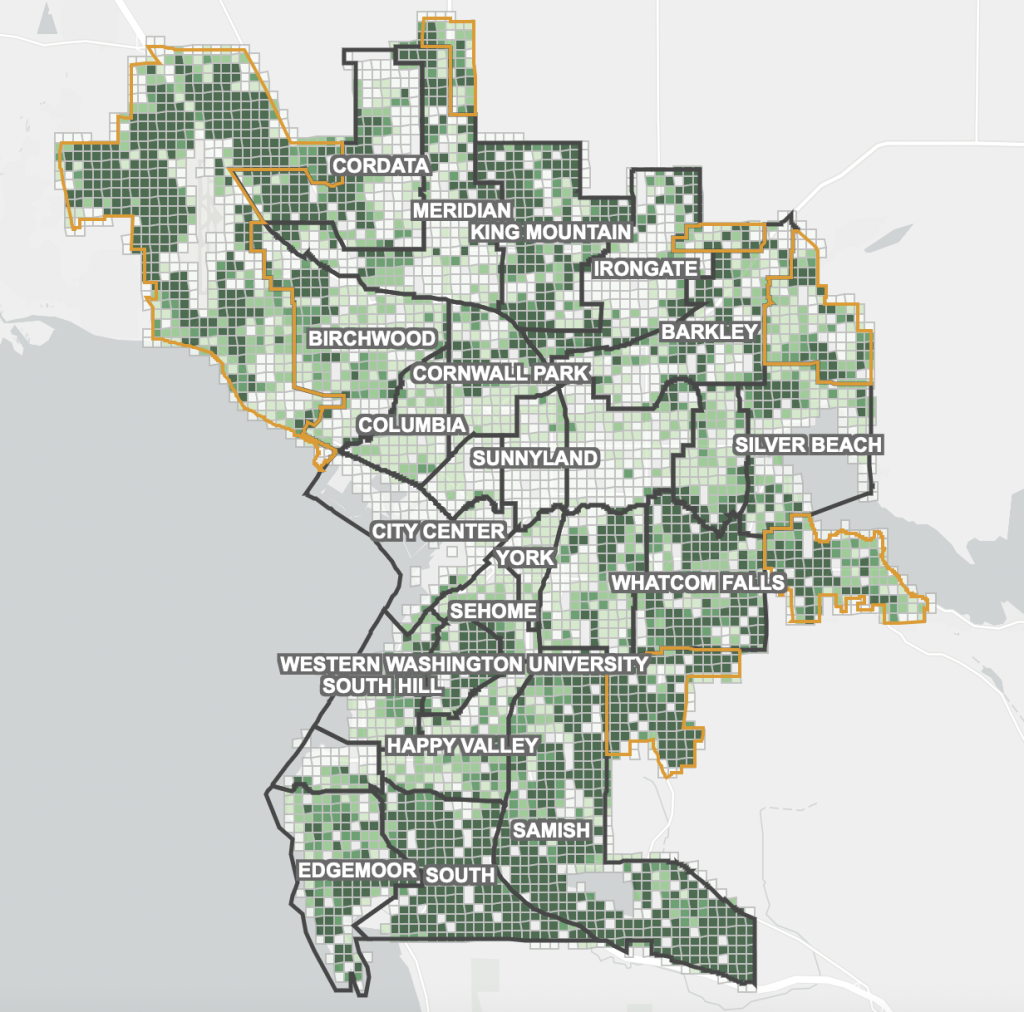

Smaller, growing cities like Bellingham are focusing on long-term plans that give a balanced approach to growth and natural resource management. Blake Lyon, Director of Planning and Community Development for the City of Bellingham, said the city is working with the existing land to minimize impact and still meet some of the housing needs that Bellingham has as a community.

The City of Bellingham is looking to complete its Urban Forestry Management Plan for the summer of 2023. In an email, Analiese Burns, Habitat and Restoration manager for Natural Resources, said the purpose of developing a new Urban Forestry Management Plan is to review this balance with specific focus on trees and forests and refine the City’s approach as necessary.

“We are in the midst of developing the plan,” Burns said. Bellingham is currently preparing its Urban Forestry Management Plan for approval between August and October of this year.

In already dense areas, like Seattle, governance is turning its eyes to redevelopment and equity. On April 13, the Department of Natural Resources and American Forests announced the launch of the Tree Equity Collaborative, “a statewide partnership to achieve tree equity across the Evergreen State by expanding and fortifying neighborhood tree canopy cover,” explained their press release.

Seattle is among the first cities to join the collaborative, pledging an equity plan for the end of 2024. The idea of tree equity and preservation is at the forefront of the city’s Urban Forestry Commission.

Patti Bakker, Coordinator for the Urban Forestry Commission, said the commission’s work is related to questions on what neighborhoods are experiencing, forest distribution and making sure that all residents have equitable access to the benefits provided by trees.

Growth management

Urban forests are vital components of healthy communities. They provide watershed management, carbon sequestration, air pollution removal, habitat, heat island mitigation and public health benefits. According to the City, Bellingham’s urban forest offsets 6,653 passenger vehicles through annual sequestration per year.

Burns said the forest canopy is one of many ways for Bellingham to address environmental impacts. “With an increasing population and changing climate, the City cannot rely entirely on forests and must use a variety of tools to support natural resources and maintain a high quality of life for all community members,” she said.

Estimates made by i-Tree Canopy indicate that Bellingham’s trees help remove 302 tons of air pollution each year. That number could grow as, according to the City, 59% of trees within city limits are recognized as young and short trees. Burns said mature trees provide greater canopy coverage and forest benefits compared to younger trees.

Most of the larger trees and mature forests reside in Bellingham’s Urban Growth Areas which represent an additional 2,325 acres of forest. Burns said development decisions in those areas weigh a variety of values to determine what is in the best interest of the community.

“Such values include protecting high-value habitats, planning for climate change, providing affordable housing, protecting water quality, providing equitable community services, and maintaining public safety,” Burns wrote.

Much like Seattle, Bellingham is experiencing a variety of housing needs. According to the City’s draft Consolidated Plan for the 2023-2027 period, housing in Bellingham is too expensive for the growing population and doesn’t meet the needs of the town’s demographics.

The City is looking to ensure additional resources that help support the growing population while protecting and preserving present natural environments. “We’re trying to get housing numbers up, we’re trying to keep costs to the point where people can afford the units that they’re living in, whether that’s rental or ownership,” Lyon said. “But we want to protect and preserve our community and our environment. So it is a challenge to do both.”

Bellingham touts 40% tree cover within city limits, representing 7,252 acres of the diverse canopy. The goal is to maintain that percentage across the city.

Urban villages and compact in-fill areas are tools to allow for development and sustain Bellingham’s current environment, according to Lyon. “By having those compact urban areas and those urban villages among other things, it helps to take the development pressures off of some of those other areas that have more green and more open space like Lake Padden or Lake Whatcom,” she said.

Permit data as of March 2022 indicates a total of 2,800 housing units were added in Urban Villages, representing 40% of all new housing in Bellingham since 2006.

“Keeping that perspective in mind is certainly beneficial when it comes to thinking about how we manage our growth overall,” Lyon said.

Learning from redevelopment

While Bellingham and Seattle are very different cities, their comparable housing issues create the same questions for city governments to consider with urban forestry.

As Seattle continues to redevelop to meet its housing demands, the City is trying to reverse the latest decline in its urban canopy and ensure the protection of trees within city limits. “We know we need to increase canopy and build the forests of the future,” Bakker said. “But we also need to maximize the potential for canopy growth that we have currently by maintaining those existing trees.”

The Green Cities Research Alliance estimated that “the replacement value of Seattle’s existing urban forest (the cost to re-plant trees and nurture them to their current size) is close to $5 billion,” Seattle’s 2020 Urban Forest Management Plan notes.

To support the urban forest through Seattle’s redevelopment, Staley said there will be requirements that incentivize the preservation of existing trees or require tree planting on streets and on properties.

But as Seattle works to offer housing opportunities across the city, Staley said a tradeoff is inevitable, at least initially.

“When new development happens, in the short term, it definitely does decrease the canopy cover on-site, but then it also results in the planting of a lot of new trees,” Staley said. “Over time, that creates the potential for getting back to canopy cover that we used to have.”

On a regional level, Staley said development in Seattle is a clear win in terms of natural resources and sustainability as density in the city prevents urban sprawl. “Within Seattle, it becomes a lot more complicated, obviously as you accommodate more housing in the city, there’s just gonna be less space for tree planting,” Staley said. “But there’s a lot of things you can do to make sure that that space you do have is well used.”

Staley said the High Point neighborhood, a place that was redeveloped in its entirety, is a good example of that. “Because of the work they did to preserve trees and plant new ones, [the High Point neighborhood] has more canopy today than it did 10 years ago when that development happened,” Staley said.

Seattle has experienced a decrease in its tree canopy in recent years, but Staley said development has not been the root cause of the decline.

“Places like Downtown, Capitol Hill, Ballard, that have had really intense redevelopment have not actually been the neighborhoods that have experienced the biggest reduction in tree canopy,” Staley said.

Seattle’s Land Use Committee is scheduled to vote on Mayor Bruce Harrell and Councilmember Dan Strauss’s updated Urban Forest Protection Ordinance on April 26 before it is presented to the full city council for a vote on May 9. The proposed ordinance’s aim to increase canopy by requiring the installation of street trees along with new residential developments. But as parts of the city saw a decline in the tree canopy, they also aim to protect what is already there. The legislation also would establish a new tier system to recognize protected trees and replacement requirements.

Equity in the cities

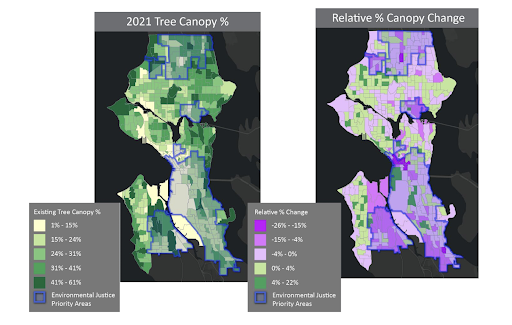

The latest accounting of Seattle’s canopy, dating back to 2021, shows Seattle has 28.1% canopy cover.

“It’s not the amount of canopy that we hope to have,” Bakker said. “We hope to have at least 30% canopy cover city-wide.”

Of the 53,505 acres Seattle rests on, 15,167 acres are covered by the urban canopy, the majority of which lies on private property. Neighborhood Residential areas represent 47% of the city’s canopy. “We know that there’s not enough canopy or not as much as we would like to have for offsetting emissions and providing all those benefits for our residents in our neighborhoods,” Bakker said.

The notion of tree equity in neighborhoods around the city is a big part of the commission’s work in Seattle. “If we look at individual neighborhoods and parts of the city, there are certain areas of the city that have much less than 20% canopy,” Bakker said, adding that the current disparity results from Seattle’s history of redlining, lack of investments and disinvestment.

Parts of the city Bakker mentioned were Rainier Beach, parts of the Duwamish Valley neighborhoods, Georgetown, South Park, part of the International District and the south end of Beacon Hill. “Even though we’ve been investing in prioritizing our low canopy neighborhoods,” she said, “it hasn’t been enough investment to overcome the challenges and reverse the disparities.”

Neighborhoods like Greater Duwamish, the Delridge neighborhood, North, Northeast, Southeast Seattle and the Central District are designated by the City as Environmental Justice Priority Areas.

In Bellingham, Burns said the canopy change analysis included an equity analysis that showed lower canopy coverage in areas with denser development. “Equitable access to forest benefits is an important Bellingham community value incorporated into the Urban Forestry Management Plan process,” Burns said. “As part of developing the Plan, staff and consultants will evaluate ways to increase equity.”

The City of Bellingham said the public will have an opportunity to provide feedback on potential actions once a draft plan is available for review.

In her poem “The Snow Pearls,” 19th-century Bellingham author Ella Higginson described the Pacific Northwest as one where “every fir tree flashes out like a tall gilded spire.”

With modern-day challenges ahead of the region, cities will have to find ways to preserve that heritage for all to benefit.

Clifford Heberden

Clifford Heberden (he/him) is a freelance journalist focused on the environment, climate and justice. A French native, Cliff moved to Washington State to pursue his journalism degree and then began publishing articles with Salish Current. Now a Seattleite, Cliff accepts 70 degrees as sunbathing weather. His Twitter handle is @cliffbutonline.