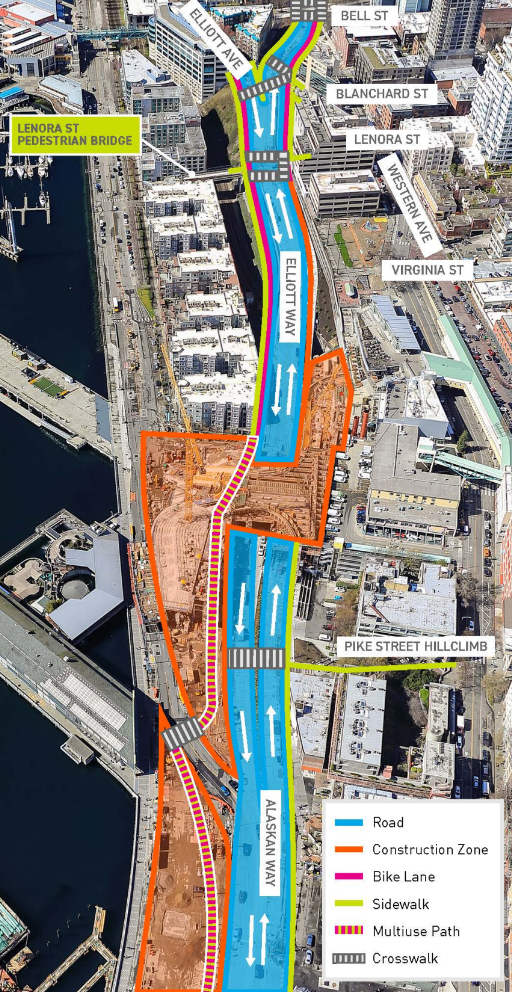

This coming Monday morning at 6 a.m., the City of Seattle will open a brand new four-lane roadway, connecting the city’s central waterfront with high-traffic streets north of Pike Place Market in Belltown. The new street, called Elliott Way, is years in the making. It sits on the former footprint of the Alaskan Way Viaduct, which included on and off ramps into Belltown before entering a now sealed tunnel underneath Battery Street.

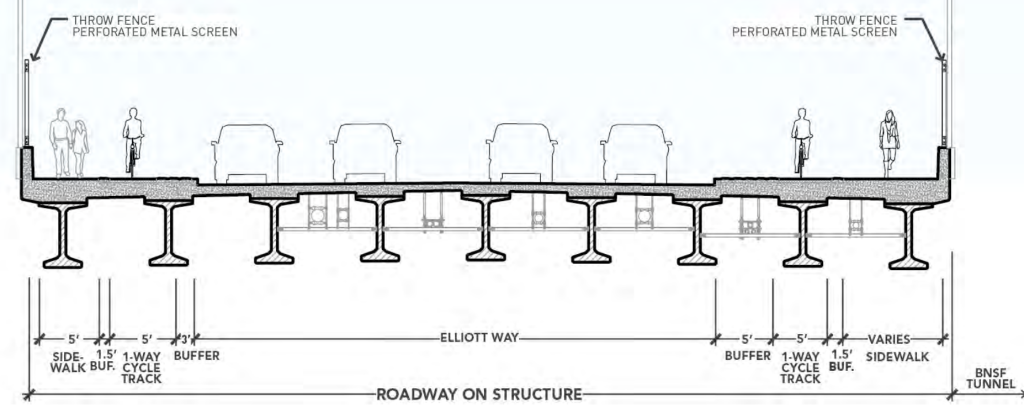

The new road will allow all vehicles heading from the waterfront toward Interbay and Ballard to bypass an at-grade railroad crossing at Broad Street. The construction has gone under-the-radar as part of the overall waterfront redevelopment project, with the promenade and Overlook Walk pedestrian connector to the new aquarium building, still under construction, taking center stage in most of the project’s renderings. When the new road has been shown in renderings and promotional images, those images have primarily focused on the view from the sidewalks, minimizing the size of the 44-foot roadway that will carry two lanes of traffic in each direction.

This week, Mayor Bruce Harrell joined dignitaries including Port of Seattle Commission President Sam Cho and Washington State Department of Transportation Secretary Roger Millar in celebrating the roadway’s impending opening, paring this event with a new honorary street name — Dzidzilalich — for the entire Alaskan Way and Elliott Way corridor from Dearborn Street to Bell Street. The honorary name honors the Coast Salish people that Seattle’s founders violently forced out of what is now south downtown.

The new roadway is being framed as essential for the movement of goods, despite the fact that the city was able to live without the connection just fine for the past four years since the Alaskan Way viaduct was closed. “We can create a livable, thriving city, with a strong freight and maritime industrial economy,” Mayor Harrell said Monday. “That’s what this represents.”

The news is considerably dampened for people who were looking forward to the new bike connection coming with the new bridge. Even though the four new general-purpose lanes will open in the coming days, only half of the pedestrian and bike connections will open at that time. Due to the continuing construction of the Overlook Walk at Pike Place Market, the northbound bike lane and sidewalk on the city side will remain closed until next year. This prioritization of vehicle traffic over other users mirrors the phasing of the rest of the waterfront corridor, where the vehicle lanes on Alaskan Way will have been fully open for over two years by the time the full waterfront bike trail from Yesler Way to Pine Street is completed.

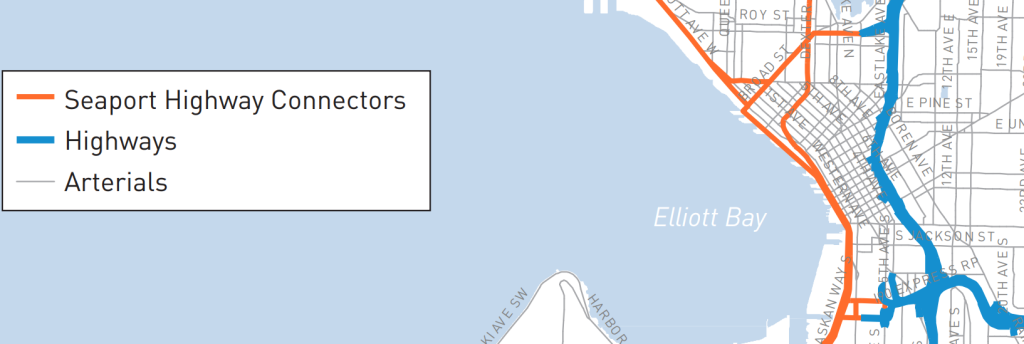

Seattle’s Freight Master Plan, last updated in 2016, does a good job illustrating why Elliott Way was created, and why it’s appropriate to label a highway connection. The broad new roadway links the state highways of SR 99 and SR 519 in south downtown and the de-facto highway corridors that serve the industrial areas in Magnolia and Ballard. Like 2020’s Lander Street overpass, eliminating the at-grade railroad crossing at Broad Street has long been a goal of freight advocates, but little analysis was done on the potential impact that the expanded general-purpose vehicle capacity will have on the city’s goals around reducing vehicle emissions. The design for Elliott Way, finalized only months after the city adopted a visionary Climate Action Plan in 2013, is at odds with the direction the city purports to want to go.

City officials praised the new roadway as being an improvement on the old double-stacked viaduct. “The vehicle-centric Alaskan Way Viaduct has long separated the waterfront from the Belltown neighborhood and we are excited to be opening a new and vital throughfare providing a multimodal connection that has not existed until now,” said Acting Director of the Office of the Waterfront and Civic Projects Angela Brady said in a release sent this week. But the new corridor will direct significant traffic directly through the heart of Belltown, even as other community assets the Office of the Waterfront promised to Belltown largely failed to materialize.

An overlook point planned at Blanchard Street early in the waterfront project failed to materialize during negotiations between the City, the BNSF railroad, and WSDOT. A small parcel dubbed the “opportunity site” had been initially put forward as a neighborhood playground in early waterfront concepts by the firm James Corner Field Operations, but that too was scaled back. City Light had been eyeing that site for a surface parking lot for electric vehicle charging, but backed away from that plan late last year, leaving its future up-in-the-air. And the largest potential piece of new open space in the area, the Battery Street Portal property at First Avenue, is being held open, potentially well into the next decade, for a possible downtown public school. The renderings for Elliott Way, which include fully grown-out landscaping and trees while they minimize the width of the roadway, belie the fact that most of the benefits of the waterfront will be seen in areas that are not Belltown.

The new roadway is taking many Seattleites, including some that have been paying fairly close attention to the waterfront project, by surprise. Even former Mayor Mike McGinn, whose term in office predates the start of major design work on the project, tweeted his surprise. “So, we just rebuilt the highway?,” he said. A 2015 presentation to the Seattle bicycle advisory board, where the designs for the overall waterfront were put forward for feedback, includes only one slide where Elliott Way is included, with no designs shown for the planned bike lanes or sidewalks. The sidewalk on the Elliott Bay side, the only one that will be opening before 2024, is only five feet wide, substandard for any new development in Seattle’s downtown.

While the City likely expects walking and biking advocates to be happy with the fact that they were accommodated on the new arterial at all, the disconnect between the celebration of this new highway and many of the city’s widely-touted goals around climate, safety, and neighborhood vitality is simply unavoidable. Boosters would do well to face that disconnect head-on. While the fact that Seattle will (eventually) have a new connection for all modes between the waterfront and the city’s densest residential neighborhood is undoubtedly good, the missed opportunities here are so large you could drive a truck through them. Four trucks, in fact.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.