In time for Earth Day, a beautiful new game that lets players unwind while unwinding civilization.

Terra Nil shows up on the App Store as “a reverse city builder.” Admittedly, I’m a little protective of my city builder games. Like, it would be weird to suggest a particular video game (SimCity) compelled me to a particular graduate degree (Urban Planning), but here we are. So reverse city building, and you have my attention.

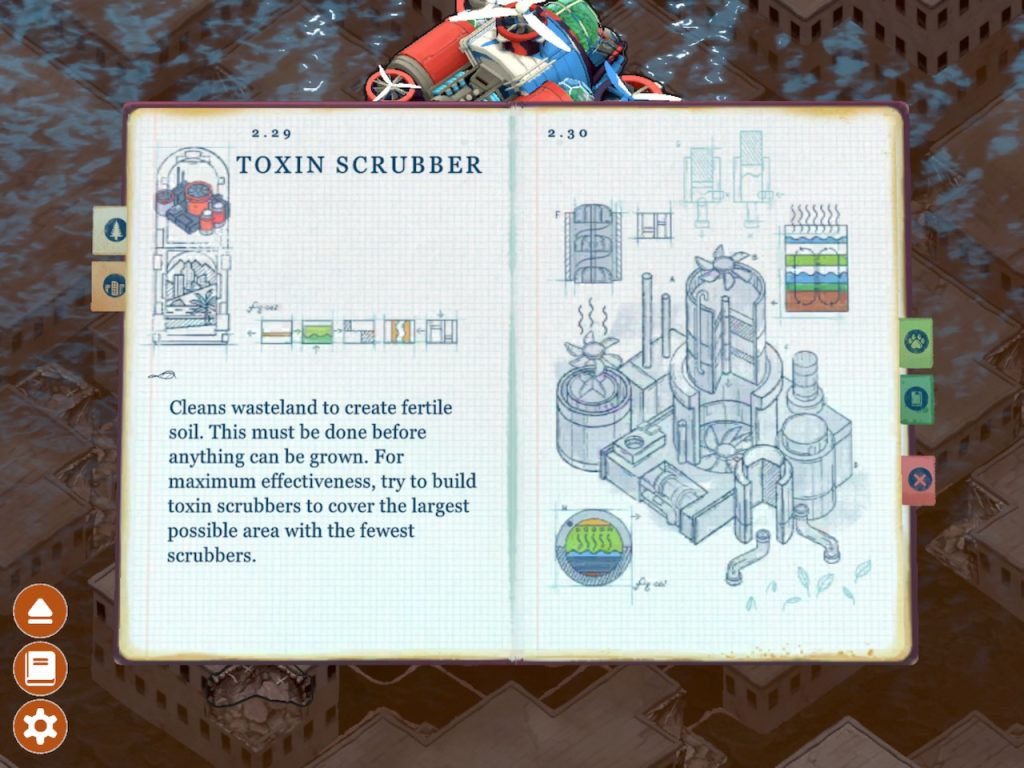

Lovely, fairly simple, with a zen soundtrack, Terra Nil has exactly the right look and feel of a game that asks you to bring life back to a desiccated wasteland. From volcanic islands to crumbling urban ruins, the game gives you a handful of tools to first decontaminate the soil, then reintroduce life to places where it’s been ruined. Slightly ironically, it does eat battery life on a tablet, so stay next to a charger.

Each level starts with a short description of the landscape to be worked and some of the initial hurdles to be unraveled. The flooded city, for example, doesn’t have enough plantable land between the ruins. So that needs to be reclaimed from the sea floor with dredgers. But the dredgers make the land unstable and too much digging will result in damaging earthquakes. Other biomes require the player to treat tainted land or blast open volcanic rock.

There is a cost to each of these actions, and a rolling tab is paid for every piece of equipment. But that account can be rebuilt with plants and animals. After the initial wave of decontamination or soil prep, irrigators can be installed to start greening the level. As these moderate the atmosphere, new plants arrive and can be installed with other types of equipment.

As each stage progresses, the biomes start to differentiate. Tundra turns to trees. Stones turn to lichen forests. Deep water turns to coral reefs. At the edges of these, animals appear. When the land achieves a certain balance, it’s time to clean up. You get an airship and transport system, then have to step backwards from the outside of the map, recycling equipment as you go. Once the garden is set, you lift off for the next level.

Lovely and zen casual games on a portable device make it sound like the game will fall into a certain category, so let’s dispatch that right now. This game is not going to appeal to someone that’s on the Candy Crush end of things because there’s not the casino payout flash of matching jewels. Terra Nil also doesn’t have a lot of the appeal of the idle games where points just accrue to unlock more ways of making more points accrue.

There’s a handful of games that came out a while back that were like little Rubik’s Cubes or puzzle boxes. They were more procedural or sequential, not about button mashing skill so much as rewarding the player finding hidden connections. Hitting the blue button would drop a seed, but it would only grow into a tree if you had opened the river gate the turn before. They’re some of the few games that I took notes.

The hardest part I ran into in Terra Nil was a stage where I had not prepared enough land to install the sunflower field. That would be fine, except there was only one chance to get it right. You either did or didn’t have enough space for the sunflowers. If you didn’t, it was time to reset the puzzle box and start the sequence all over again.

And that stands in stark contrast to city builder games. The beauty of SimCity, like its real world counterparts, is that the game is iterative. Yeah, there’s losing scenarios. (City hit by an earthquake right after you blew your budget for a stadium! Fiction is so weird.) But there are also unlimited ways to get to the winning ones, including working the problem. Terra Nil’s puzzle box doesn’t have that kind of leeway. Early mistakes can be irreversible.

Where the underpinning of Terra Nil is an unlocking contraption, the base structure of SimCity is a concept called The Game of Life. Not the one with the little cars and pins, but the one developed by mathematician John Horton Conway in 1970. It’s flickering lights on a grid, where the squares have to obey certain rules based on the state of their neighbors. Off squares, or “dead” cells, stay dead unless they have three “live” or turned on neighbors. Live cells only stay alive if they have two or three live neighbors. Fewer living neighbors and they die by underpopulation, too many living neighbors and they die by crowding. Every generation or turn checks every square on the grid, and cells switch to alive or dead. Rules for lights on a grid is a game only a mathematician would understand much less adore, and even its creator fell out of love.

Until you see it in action. Some shapes are frozen stable, like a 2×2 square where each of the live cells has three neighbors and none of the surrounding dead cells has enough to change. Other shapes are oscillators, that change in place. Certain bars just flip where they are and stars twinkle. Then there are the movers. Five square shapes that glide across the screen. Rolling, heavyweight figures that have been named spaceships by theorists and special arrangements of breeders that can spawn them.

And once you see Conway’s Game of Life underway (you can play around with a version here) it’s impossible to miss its connection to SimCity. Too much industrial pollution and your residential areas stay dormant. Commercial served by train and roads sprouts to a tower. The square zones live or die by what they’re next to. Success emerges from the interaction between cells, and there’s always the opportunity to make small tweaks or grand gestures to realign the entire game. Very much the way to build a city, either digital or meat space.

It is a little unfair to compare a recently released app about flowers to one of the most transcendent games of all time. And Terra Nil does offer both Gardener and Zen modes that make the game easier or let you just putter around without specific objectives. But it is useful to consider what it takes to make a game like SimCity so different. Surprises don’t necessary come from proscribed achievements from hitting the right key sequence. Surprises and achievements and healthy cities come from emergent interactions.

Which makes Terra Nil absolutely successful. Treating a city like a jewel box is a perfect city unbuilding simulator. If you want to take apart a neighborhood, there is nothing like adding too many rules or pretending it’s a terrarium. Boiling down urbanism’s iterative game of life to just rote procedures is absolutely the way to dismantle a city.

Terra Nil was developed by Free Lives and published by Devolver Digital. It is available on Steam, and free on various app stores with a Netflix subscription.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.