The Seattle City Council is closer than ever to tapping a new source of revenue for transportation projects, with councilmembers from opposite sides of the ideological spectrum likely to be on board. Following years of city work, transportation impact fees are being advanced, with a potential project list already presented to the council this spring. But at the moment impact fees are set to be on the table, the City of Seattle is facing a revenue forecast that shows multifamily home construction slowing significantly, prompting the question of whether the timing is right to add yet another cost barrier onto the construction of new housing.

Impact fees are one-time charges assessed on new residential or commercial construction under the assumption that this growth will produce a demand on public infrastructure that needs to be offset. They can be assessed to fund schools, fire protection, parks, and transportation infrastructure. In contrast to many Washington cities, Seattle has not assessed an impact fee, but has been pursuing one in earnest since 2014. In 2018, the city took a major step toward implementing them by issuing a determination of non-significance (DNS) under the state environmental policy act (SEPA). That DNS was appealed by a group of property owners calling themselves the Seattle Mobility Coalition. Seattle’s hearing examiner found some of their claims credible and remanded the DNS back to the city for further work in 2019, and it took until 2023 for it to be reissued. It was promptly appealed again by the same group.

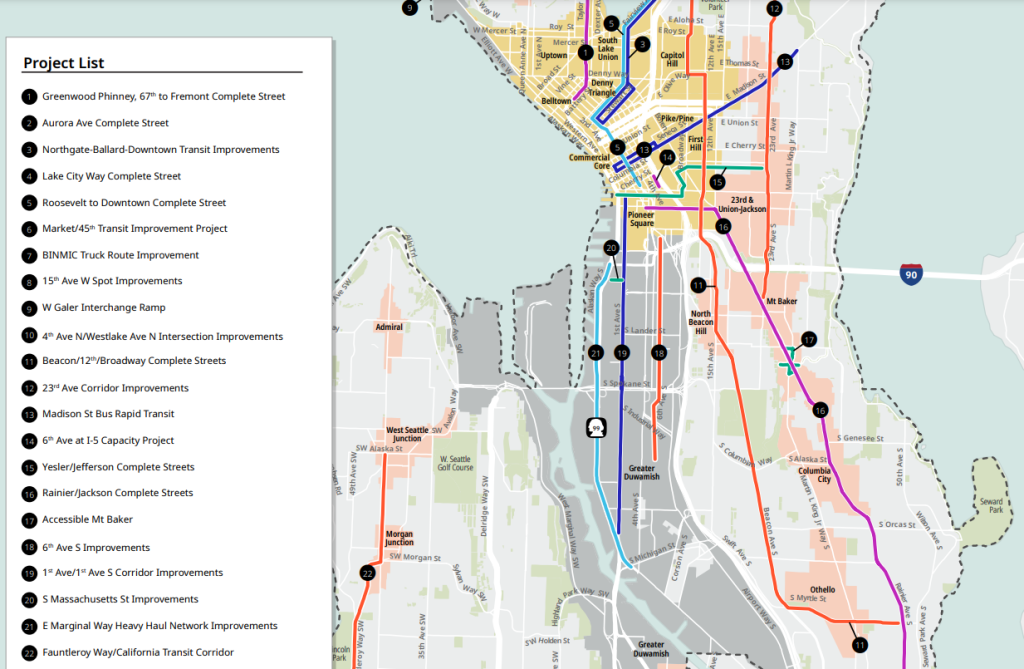

Until that appeal is resolved (a hearing is now scheduled for late May), Seattle cannot move beyond the initial rate study for impact fees, which includes a potential ceiling for the fee. Only certain transportation projects are eligible to be funded by impact fees, and often only certain elements of those projects as well. The fee is required to fund only the elements of a project that provide new capacity that would ostensibly be used by the new development, a so-called nexus between the impact and the fee being charged. The city is working to update that list of projects now, and in March, the council’s transportation committee received a briefing on them.

The current city council is particularly likely to try and implement impact fees this year, if the resolution of the legal appeal allows them to do so. Both sides of the council’s ideological spectrum have spoken in favor of approving impact fees in recent years. “The obstacles to progressive funding for sidewalks, bike lanes, and intersection improvements are the same as for other forms of transit funding. We need to expand the revenue base by taxing big business and the rich. We need impact fees on corporate developers,” Councilmember Kshama Sawant told The Urbanist in 2019. Councilmember Alex Pedersen, one of the most conservative members of the council, has also come out in support, touting them in several recent email newsletters. Both councilmembers are set to leave office at the end of the year, likely making 2023 pivotal.

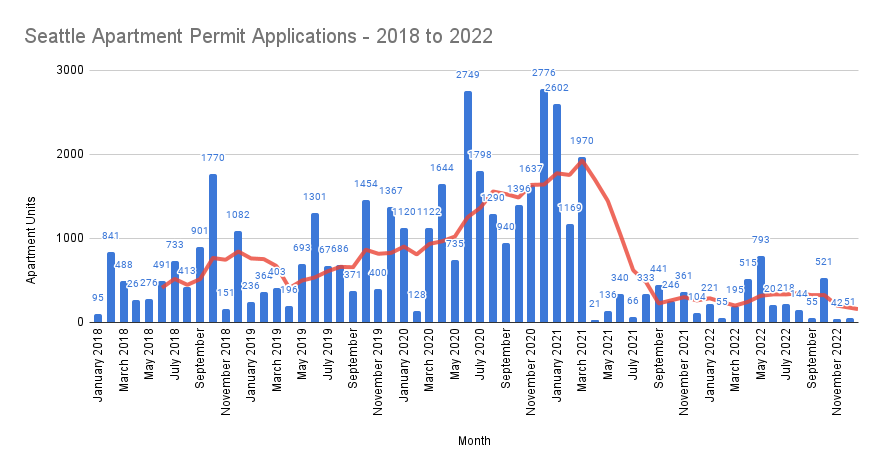

But new revenue forecast information coming out of the city’s independent Office of Economic and Revenue Forecasts suggests that the city could be in for a sustained lack of growth in both multifamily residential and commercial building construction. The drop off in multifamily permit applications was already known, but Ben Noble, the office’s director, was clear that the outlook was not set to improve. “We’re seeing less multifamily development for the same interest rate and market dynamics,” Noble said, suggesting there are unique factors at play in Seattle’s predicted apartment slowdown. And Noble was even more clear about office development. “I don’t think anyone’s going to build an office tower in the city for a long time,” he said.

With added costs like the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) fee and new requirements under the building code being blamed, at least in part, for that slowdown, the question of whether added impact fees will chill development even further will be expected to come up in the discussion. But impact fees are a politically easy sell, with most existing residents within the city not affected by them.

A Dusty List of Projects

The City has identified a $1.6 billion list of projects that would be eligible to receive at least partial funding from transportation impact fees. The project list includes a number of full “complete street” corridors that would fill badly needed gaps in the city’s transit and bike network, including Aurora Avenue, Beacon Avenue, Broadway, Rainier Avenue, and Jackson Street. Many of these projects are merely conceptual at this point, with the actual sausage-making around how they would modify some of the street’s most important corridors left to a much later date.

The list includes a number of projects designed to improve vehicle throughput, often in the guise of improving freight capacity. A $12 million project along 1st Avenue S in SoDo, for example, promises to “improve operating efficiency and safety for all modes by adding extensive intelligent transportation systems including traffic cameras, vehicle detection, and traffic responsive signals,” according to the project description. A speed study from January on 1st Avenue S, northbound at Spokane Street, found one in four drivers exceeding 35 mph (the signed limit is 30 mph) and one driver, on average, topping 70 mph per day. What exactly the “operational” improvements could be made to the street that are in line with the city’s safety goals are unclear.

Some projects seem even more blatantly at odds with the city’s decade-old climate action plan, which called for an overall reduction in the number of miles traveled in the city by 2030. A $50 million project to “build capacity” to 6th Avenue at I-5 near Yesler Way doesn’t even seem to have any nexus with active transportation. It’s not clear at all how connected this project list is with the Seattle Transportation Plan, intended to be integrated with the 2024 update to the City’s comprehensive plan, given the fact that most of the projects on this list appear to have been sitting on a shelf for a very long time.

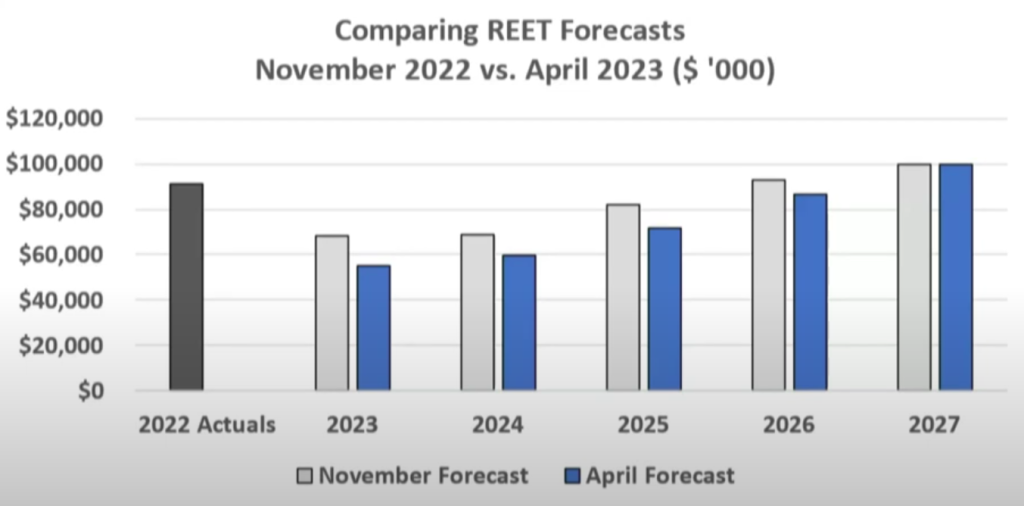

REET Downturn Could Delay Existing Transportation Projects

There is another aspect to the city’s financial picture that will likely bleed over into the discussion around impact fees: an expected downturn in real-estate excise taxes (REET), which the city collects on any real estate transaction that occurs in the city. “The speed at which REET revenue has declined has caught us all off guard,” Noble said at last week’s forecast council meeting. He noted that since the city collects REET specifically for long-term capital projects, the impacts of a downturn in REET collections will likely be felt long-term, and this could impact many of the same projects that the city might be eyeing for transportation impact fees.

Even though a slowdown was anticipated in last year’s revenue forecast, things are not improving. The City is only expecting to collect around 60% of the amount from REET that it did last year, with recovery not expected until around 2027 at the earliest.

These churning revenue forecasts are likely to intensify the push for impact fees. Alex Pedersen, chair of the council’s transportation committee, suggested in March that impact fees could become a new source of revenue for transportation projects that haven’t been able to be funded yet. “We saw the city budget constraints we had last year and the year before, when we were unable to fund several multimodal transportation projects,” he said.

The councilmember has also suggested impact fees could take the place of either property taxes, which fund the entirety of Seattle’s current $930 million Move Seattle transportation levy (up for renewal next year), or sales taxes, which fund bus service and specific physical transportation project via the Seattle Transit Measure. Pedersen opposed Move Seattle in his role as a neighborhood advocate in 2015, calling it “too expensive” and claiming that it wouldn’t promote “racial and social justice” by funding too many protected bike lanes.

Councilmember Lisa Herbold, who has supported impact fees for quite some time, co-authoring an op-ed in support of the idea 2017 with former Councilmembers Sally Bagshaw and Mike O’Brien, chastised those who were already pushing back on the idea of impact fees while the City is still in this early step.

“We are not at this time deliberating on an impact fee program,” Herbold said. “Because so many people are opining — already — on the impact of impact fees before we even have the requirements that are, again, necessary before even deliberating on a program, I just think it’s really important for public education to explain exactly where we’re at right now. We are only talking about what are the projects that would theoretically be eligible to receive funding from an impact fee if the City of Seattle were to enact one.”

But if the appeal of the SEPA determination of non-significance is resolved within the next few months, there will likely be a concerted push to move forward on impact fees. The question of whether this is the right time to add those fees on will remain salient, given the fact that the city has been able to live without them for quite a long time.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.