As different elements of Seattle’s waterfront overhaul are beginning to open to the public, Seattleites of all stripes naturally have many opinions about how things are turning out. Given the fact that most of the central pieces of the new waterfront, including the rebuilt Alaskan Way and the pedestrian promenade and bike trail still being constructed alongside it, were all designed over a decade ago, many people are seeing things go into place with fresh eyes, not having had a chance to weigh in on any of the elements.

A final piece of the waterfront project is being designed right now, and the City of Seattle’s Office of the Waterfront and Civic Projects is choosing to largely disregard feedback from members of the public telling them to be bold and reconsider some core assumptions around vehicle access. Earlier this year, The Urbanist reported on work kicking off to redesign a two-block stretch of Bell Street, from First Avenue to Elliott Avenue. Situated at the very northern edge of the waterfront’s footprint, where a number of public realm improvements have either been cancelled or deferred, the project offers a chance to connect one of Seattle’s densest residential neighborhoods with the rest of the waterfront project.

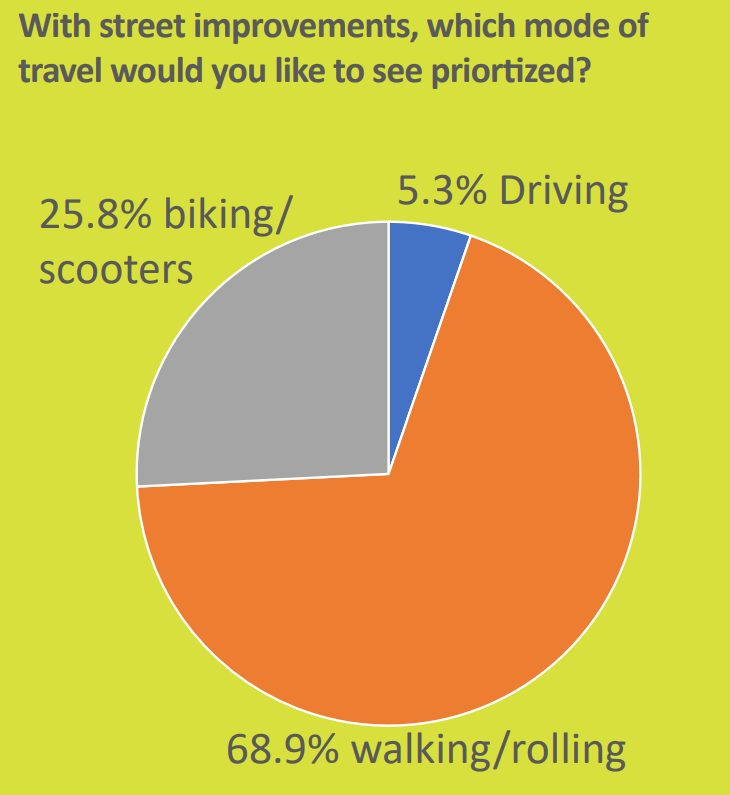

In late January and early February, the city conducted an online survey of the project that received over 500 responses. Over 94% of respondents said that improvements to the street should prioritize people walking and rolling or biking and using scooters, with just over 5% saying that improvements should prioritize people who drive. Many of the comments submitted by respondents requested that the street become fully closed to through traffic so it could become pedestrian space. “The safe street portion of bell street is much better than this section, and it would be even better for biking if it was closed to cars,” one person wrote. “The biggest improvement that could be made is to close it off to cars and replace the street with tables and spaces for people to hangout,” another wrote.

But the Office of the Waterfront is taking a narrower view of the potential pathways forward. Last month, during a meeting of the Seattle Design Commission to discuss the project, Office of the Waterfront project manager Terese Casper told the commission that they will not pursue full pedestrianization.

“We feel we’re already significantly de-prioritizing vehicles,” Casper said. “There does need to be a vehicle lane.” But alternatives to a through lane that could still provide access to current and future egress aren’t being considered either, and dead-ending the street at the alleyways wasn’t considered desirable “from an urban design perspective.”

The two design options being advanced both include a wide travel lane — 14 feet — which would be one-way, with traffic along both blocks of Bell headed toward Western Avenue. The first concept, which is being called “rooms”, would devote a section of pedestrian space along the south side of Bell Street to seating and a “community gathering plinth,” which is still being designed. People on bikes would have a full protected bike lane heading toward downtown, but no facility heading toward the waterfront until they cross Western Avenue.

Either option currently on the table is being designed around one salvaged highway sign from the Alaskan Way Viaduct, which formerly entered a tunnel near the site. Similar to plans that added a piece of the “ramps to nowhere” into the final piece of the UW Arboretum after the Highway 520 bridge project is completed, the sign is intended to be a nod to the city’s history of civic activism. Of course, the reclaimed feature could just as easily be seen as evidence that the city isn’t ready to let go of its car-dependent past.

The second option, called “garden pockets,” isn’t dramatically different from the first, with some tweaks to the seating arrangement, again on the south side of the street, and with a two-way protected bike lane extending all the way from First Avenue to Elliott Avenue. This would likely provide better connectivity to the new Elliott Way roadway down to the waterfront, which will have one-way bike lanes on either side of it.

Seating is likely to be a contentious issue in any design, with many neighborhood residents in Belltown advocating for less seating with the thinking that places to sit will encourage illicit activities. “People want seating, but then all the seating got removed [on Bell Street Park] because of what was happening there,” Casper said. “I don’t think you’ll see as much seating as what’s in the concepts.”

Jackson Teal is a Belltown resident who has been following the process around what these two blocks could look like. “The Office of the Waterfront [OOTW] has done a really great job with outreach, but then just ignored it,” he said. “I think the problem is that the OOTW and SDOT had a set of design parameters already in place prior to the outreach. I’d love to know what they thought the outreach would show, but regardless I think they’re now just trying to make their original plan fit the outreach data rather than the other way around.”

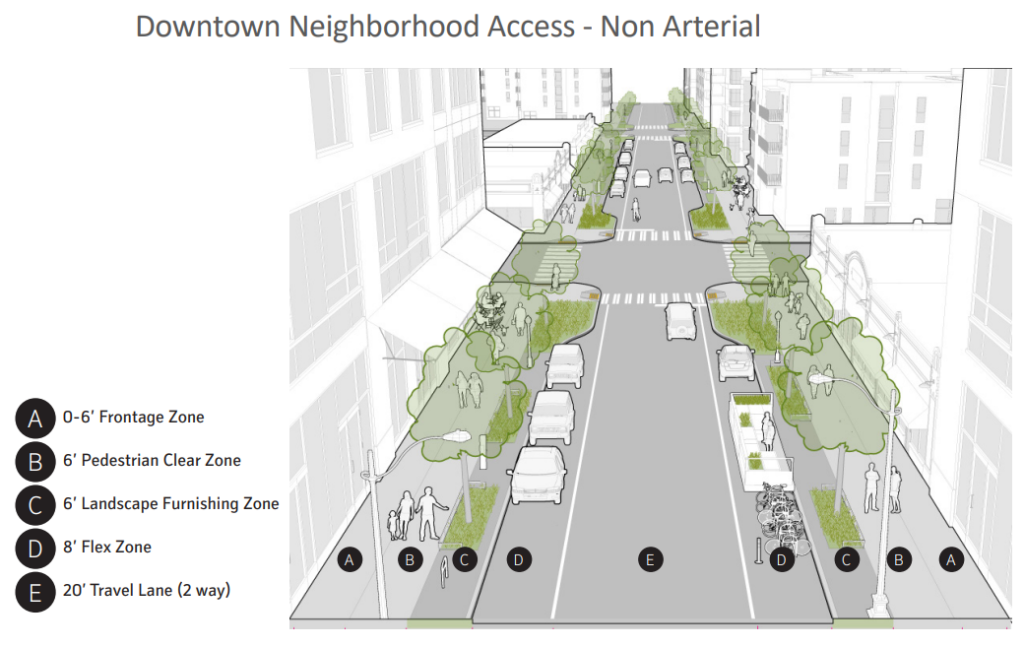

Another factor constraining the city’s thinking around Bell Street could be SDOT’s design manuals. An early March presentation to the Belltown Community Council included a slide noting that Bell Street’s current street — as a “downtown neighborhood access – non arterial” street — includes, generally, two-way vehicle access as well as a “flex” lane on both sides of the street, nearly always parking or loading. Seattle doesn’t have any street typologies for pedestrianized streets, one possible reason why there is a dearth of them citywide. Or the dearth of them citywide is the reason the city hasn’t included them in its typologies, having to reinvent everything that’s successful in other cities from scratch. It’s hard to say.

But missing opportunities here to rethink how a few blocks work, in a neighborhood lacking in open space where the city is explicitly trying to encourage more walking and biking trips, illustrates the systemic barriers still in place within a city bureaucracy that just can’t imagine turning a street with through traffic into something different.

Another big constraint on Bell Street is the relatively small budget, around $3 million. With other waterfront connection projects downtown and in Pioneer Square, with much bigger budgets, under construction or soon-to-be, it does look like Belltown got the short end of the stick, with both a lack of imagination and a lack of funds hindering what could be done here.

One possible benefit of that small budget, on the other hand, is that a full revamp of the street’s curbs, to create a “shared street” in the same way that E Denny Way at Capitol Hill’s light rail station, or Plaza Roberto Maestas festival street at Beacon Hill’s light rail station, and with another waterfront project along Pike Street near the Market. But budget constraints aren’t the only reason that’s not being pursued. “We’ve heard a lot of concerns with the curbless design,” Casper told the design commission. “The curbless design was not something we were ever really exploring for those reasons and more.”

“Overall, I’d say I’m disappointed Seattle once again can’t fathom of removing vehicles from a street, but more than that, this part of the overarching Waterfront project very much seems like an afterthought,” Teal said.

With the city keeping its visions for Bell Street incredibly constrained, it’s clear the interest lies with wrapping up this segment of the waterfront revamp with a project that doesn’t upset too many people.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.