In response, Wildfire Ready Neighbors fire prevention program launches in Western Washington

Just 10 days into this spring, a firefighting team flew in a helicopter over the dome of the Washington state capitol building in Olympia. They were on the way to quickly put out a small wildfire before it had the chance to grow along Highway 101 in the Hood Canal, an area with lush forests and a historically wet climate.

People who call cities and towns in the South Puget Sound home have watched this landscape drying out over the last few decades.

“I’ve lived in this state my entire life, other than going away for college or grad school. I’ve never remembered until recent years seeing a weather forecast for smoke,” said Congressman Derek Kilmer, who represents communities in Tacoma and on the Olympic Peninsula. “This really affects people not just in Eastern Washington, but Western Washington as well. Wildfires are devastating and heartbreaking, they are also avoidable.”

Kilmer spoke on Tuesday at the Western Washington launch of a collaborative program called Wildfire Ready Neighbors, which for the last two years has provided people in Eastern Washington with tools to prepare their properties and homes before wildfire season. It offers no-cost consultations to help people take simple steps to remove overgrown excess plants, prune overgrown trees, and other basic lawn-care that will reduce fuel for fire.

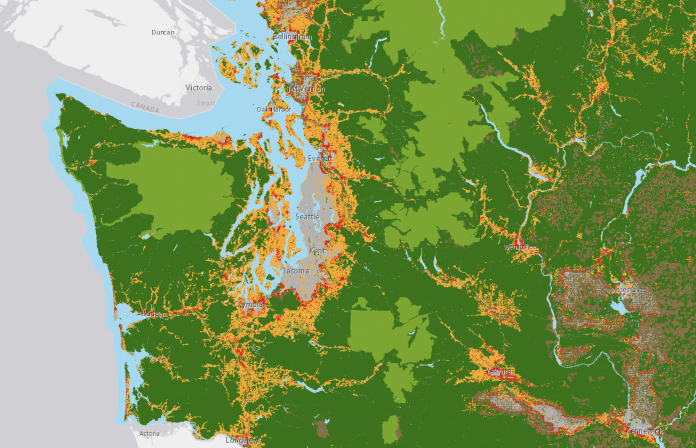

Funded through the 2022 state supplemental budget, Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) is expanding the program to Western Washington because the state now considers Pierce County, the second most populous county in Washington, high wildfire-risk in addition to Mason and Thurston. A bill this legislative session is pushing for $12.8 million over two years to further support resiliency efforts.

Nearly 30% of last year’s wildfires happened on the west of the Cascades Mountain Range. When September brought warm wind and dry air, more than 12,000 acres burned just an hour northwest of Seattle, between Skykomish and Index, prompting evacuations of 400 homes. Not only did it bring unhealthy smoke into the city, it raised concerns of what the future holds for wildland urban interfaces – a term used to describe the intersection of human activity and natural environments.

In cities, wildland fire most likely threatens infrastructure and homes near parks with urban forests and roadways with large swaths of grass, like Interstate 5. Usually, fires in these places start from trucks dragging chains on pavement or cars parking in dry grass.

That’s why it’s not just drought and record-hot summers troubling DNR leaders like the Commissioner of Public Lands Hilary Franz, it’s also the sheer density of people in the west. In 2022, all but four of the 377 fires were caused by people.

“We [in Western Washington] believe it’s a very rural issue. That it can’t happen in an urban or suburban area, and people are really wrong,” Franz said. “Every 300 to 500 years, a million acres burns in King and Pierce County, and we are in the middle of that 300 and 500 years. Obviously, 300 to 500 years ago, there weren’t so many people.”

Fire is how nature restores itself. It clears out crowded tree canopies and burns away invasive plants. Moist Douglas-fir and western hemlock forests are no exception.

Before settlers came to Washington, if a lightning strike didn’t naturally cause fire, indigenous people who lived near these landscapes since time immemorial would intentionally set low intensity burns. But since the 20th century, federal and state governments have enforced an ethic of suppression.

These early 1900 policies have compounded today’s climate-change influenced wildfire crisis. Now forests are stacked like a bonfire, fueling scorching wildfires that burn for weeks. Agencies like DNR are working with municipalities and tribes to bring back proactive fire. For everyday people, they can contribute by evaluating what’s around their home and taking action.

It’s unlikely that a large wildfire will move into places like Seattle, Tacoma, and Olympia. Smaller cities are creating a buffer between the large metro areas and wilderness, but that leaves wildland urban interfaces in South Puget Sound like Orting – where more than 7,000 people who have never lived with fire – exposed.

Zane Gibson, fire chief with Orting Valley Fire and Rescue, is among the few who have experience with both structural fires and wildland fires. A few years ago, just 10 miles north, wind gusts blew fire into his hometown, destroying four homes.

“For my entire career, we had talked for forty years about the potential of an east wind event after a dry summer in Bonney Lake, and it came true in 2020,” Gibson said. “At the same time, there was already a firestorm in Eastern Washington, so there wasn’t a lot of resources.”

The National Interagency Fire Center predicts significant wildland fire potential this summer. It could be as challenging as the taxing wildfire season in 2020, according to Franz. While winter brought ample precipitation, rain and snow slowed down in March and was below average.

While just a forecast, elected leaders and fire officials are urging high-risk communities in the wildland urban interface to prepare for the worst and hope for the best.

“The fires are burning hotter and faster, and Western Washington residents aren’t necessarily used to that fire behavior,” Gibson said. “So we’re doing our part to get our community ready.”

Ashli Blow

Ashli Blow is a Seattle-based freelance writer who talks with people — in places from urban watersheds to remote wildernesses — about the environment around them. She’s been working in journalism and strategic communications for nearly 10 years and is a graduate student at the University of Washington, studying climate policy.