Councilmember Sara Nelson has joined business leaders in opposing bus lanes.

Following the launch of the RapidRide H this month, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) is moving forward with upgrades to the six other transit corridors it promised voters with the 2015 transportation levy. With four of those corridors no longer planned as full RapidRide routes, many of those upgrades had been watered down as well. But out of the four, the upgrades to the Route 40, between downtown Seattle and Northgate via Fremont and Ballard, remain the most robust. Since 2020, SDOT has been planning to convert sections along the route that see the most bus bottlenecking into dedicated transit lanes.

The proposed improvements have come with pushback. In late 2021, The Urbanist reported on the intense pushback that the project was receiving from Eugene Wasserman, president of the North Seattle Industrial Association.

“It appears to the Maritime/Industrial community that SDOT is willing to sacrifice the viability of maritime/industrial businesses and their employees so that Amazon workers can get to their offices 5 minutes earlier,” Wasserman wrote to then-director of SDOT Sam Zimbabwe that spring, asserting that reallocating space along Westlake Avenue N and Leary Avenue NW for dedicated bus lanes would hurt maritime and industrial businesses in the area.

Wasserman asked for the department to fully restart its process for design and community engagement on the project, a request that was not successful as SDOT moved forward with design, releasing refined concepts for the project in the summer of 2022.

Since then, numerous meetings have been happening behind the scenes, with at least three city councilmembers jumping into the debate over how and whether the Route 40, one of Metro’s highest-ridership routes in Seattle, should see speed and reliability improvements through west Queen Anne, Fremont, and Ballard.

Most recently, the Fremont Chamber of Commerce, a business advocacy group that has been citing concerns from businesses in the neighborhood over loss of parking and loading zones since 2021, took a more active stance on the project, sending out emails to their members asking them to get involved.

“Be Warned! Traffic in Fremont could get much worse,” an email from the Chamber sent in early February read. That email was followed up with a second in March. “SDOT & Metro are looking to reduce bridge access to one lane each way to place a permanent bus lane cutting through our community. They are also planning on moving bus stops and removing parking,” the email read. “This action will greatly increase congestion throughout greater Fremont.”

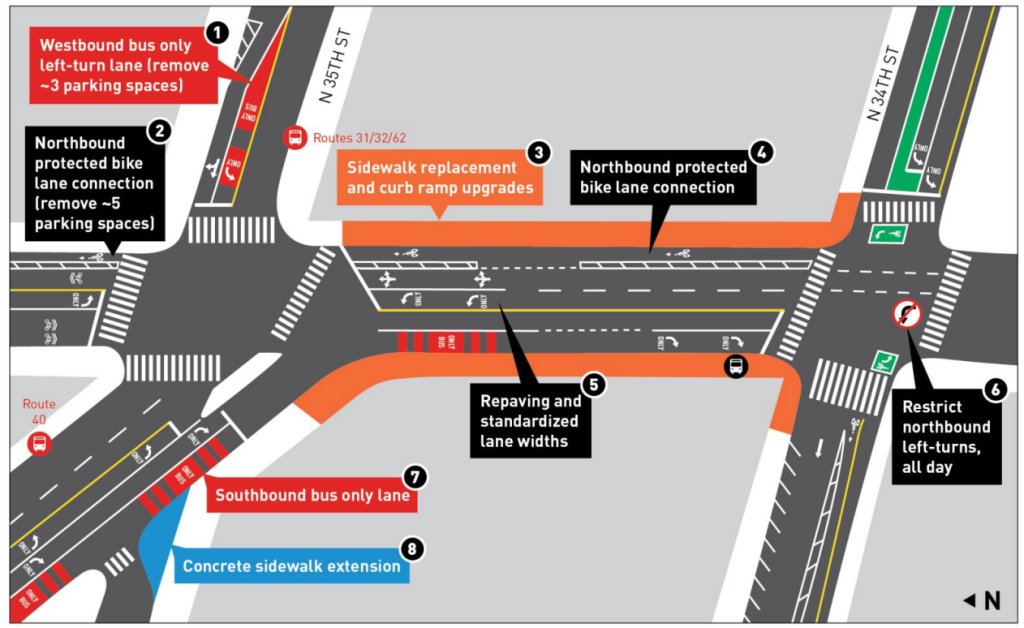

The only way the Route 40 project would “reduce bridge access” is through the conversion of one southbound lane on Fremont Avenue N between N 35th Street and N 34th Street to a bus-and-right-turn-only lane; one lane on the northbound side would turn what is mostly a bus stop into a one-way protected bike lane, with that stop relocated to N 35th Street. No changes are proposed for the immediate blocks on either side of the Fremont bridge.

A few days after that latest email alert, the Fremont Chamber held a meeting in a neighborhood business to discuss concerns with the project. At that meeting, Wasserman distributed material detailing the concerns that the North Seattle Industrial Association has with the project.

“A transit lane reserves the lane only for transit 24 hours a day, 7 days a week,” the pamphlet read. “Even in the middle of the night, only transit is allowed. Cars except for turns are forbidden. In those sections of Leary that will have transit lanes, one lane in each direction will be a regular lane and one will be a transit lane. Essentially one lane in each direction will be eliminated. The fear is that removing one lane of traffic in each direction will create traffic jams in these areas. This increased traffic will make it difficult for businesses to do all aspects of their business. For example, the Nordic Heritage [Museum] feels that increased traffic from the transit lanes will discourage their members and tourists from visiting the museum. The SDOT project staff did not do the research to show this would not happen.”

The Fremont Chamber of Commerce did not return a request for comment, nor did the campaign of Pete Hanning, the Chamber’s executive director running for the District 6 city council seat currently held by Strauss. Wasserman’s literature noted that SDOT Director Greg Spotts has agreed to meet with the coalition when the project reaches its 60% design mark, later this spring.

Even as pushback has continued, SDOT has made some concessions to voices concerned about impacts to freight mobility. An idea that did not exist when the project kicked off in 2020 was shared “freight and bus” (FAB) lanes, in which larger freight vehicles are permitted to use transit-only lanes, at least during specific hours of the day.

When The Urbanist first reported that Seattle was moving forward with potential pilot programs on a number of streets, freight-and-bus lanes along Westlake Avenue were clearly a point of potential compromise on some of the complaints raised around freight movement. Now SDOT is officially moving forward with their inclusion.

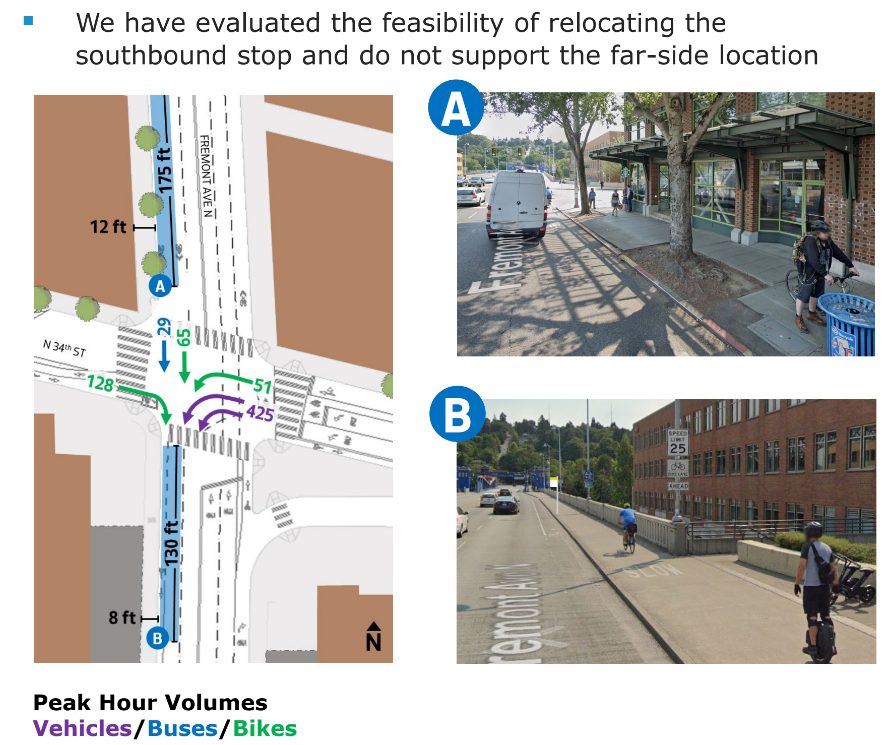

SDOT also looked at some modifications to the project that have not moved forward. A request from some Fremont businesses to relocate the southbound bus stop at Fremont Avenue N and N 34th Street, one of the busiest bus stops in Fremont, one block south to the immediate approach to the Fremont Bridge (where it had been located prior to 2007), was found to be infeasible. Riders would mostly be unable to board buses when the drawbridge is raised, and pedestrian and bike conflicts would increase, the evaluation found.

These concessions — or attempts at concessions — haven’t seemed to stem any of the criticism of the project. Wasserman has pushed District 6 Councilmember Dan Strauss to take a stance against the project, something his office has declined to do. He has provided Strauss’s office bus ridership numbers for District 6, as evidence that investments in bus infrastructure don’t make sense. In July, Strauss met with a number of Ballard business groups to discuss the project, but Strauss hasn’t come out in support of any major changes to SDOT’s plan.

Wasserman has apparently found a more willing partner in a different councilmember: Sara Nelson. Nelson co-founded Fremont Brewing, which operates a taproom in Fremont and a production facility in Ballard, but said she stepped away from the business to run for office in 2021. Following a one-on-one very early in 2022, Wasserman and others met with Nelson’s office that summer, a meeting he appeared to use that as leverage to pressure Strauss to take a position.

“Councilmember Strauss, I wanted to update you on our Route 40 coalition meeting with Councilmember Nelson,” Wasserman wrote in an email to Strauss last September. “We explained to her what the SDOT has planned for Route 40. After a discussion, she told us that she would oppose the project. I found it interesting that SDOT did not meet with her to discuss the project, particularly since one of the businesses she owns is right by one of the proposed bus lanes. We have not heard from you for a while, so we assume that you are still supporting as it is currently being presented. We hope to hear from you soon.”

In October, at a meeting of the Fremont Community Council, Nelson reiterated her position on the project directly. “My official position is I oppose this,” she said. “Taking it down to one lane for a bus lane that is perhaps not as utilized as the planners were thinking in the past to me doesn’t make the most sense.”

Nelson has jumped into a number of pre-existing transportation issues during her first year on the job, including a long debate over a protected bike lane on West Marginal Way, and meeting with opponents of completing the Green Lake Outer Loop bike lane project. But Nelson, who does not serve on the transportation committee, doesn’t appear to have made much headway on influencing these projects within the City’s bureaucracy.

As of last fall, SDOT had held over 10 meetings with different stakeholders on the entire Route 40 corridor, not including the briefings held at the request of Councilmembers Strauss, Lewis, and Nelson in 2022. So far, the tweaks made have been minor, with the goal of improving speed and reliability on the route staying front and center. Metro’s data shows they’re sorely needed, with the 2022 system evaluation showing that over one third of 40 trips were running late on Sundays, nearly one in four trips on Saturdays, and nearly one in five over the course of the entire week. But in the coming weeks, the 60% designs will truly show whether the behind-the-scenes lobbying efforts have made a difference. SDOT’s current public timeline has construction starting by the end of the year.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.