Councilmember Strauss introduces legislation to regulate 70,000 additional trees – but will the effort to boost canopy coverage to 30% slow down housing creation?

After three years of work on the issue of Seattle’s declining tree canopy, Councilmember Dan Strauss (District 6) proposed legislation last week that would quadruple the number of regulated trees on private property in Seattle and require one-to-one replacement or payment for removal of most trees larger than 12 inches in diameter.

In a city facing a severe housing affordability crisis, some advocates for housing density are skeptical of the proposal. But Strauss believes he’s achieved a balance between tree preservation and housing construction.

“Tree protection has been used as a proxy against development. And that’s not okay,” Strauss told the Urbanist. “And protecting trees has been opposed by builders. And that’s not okay. We have the ability to both protect trees and create the housing that the city desperately needs. And that’s what this bill does.”

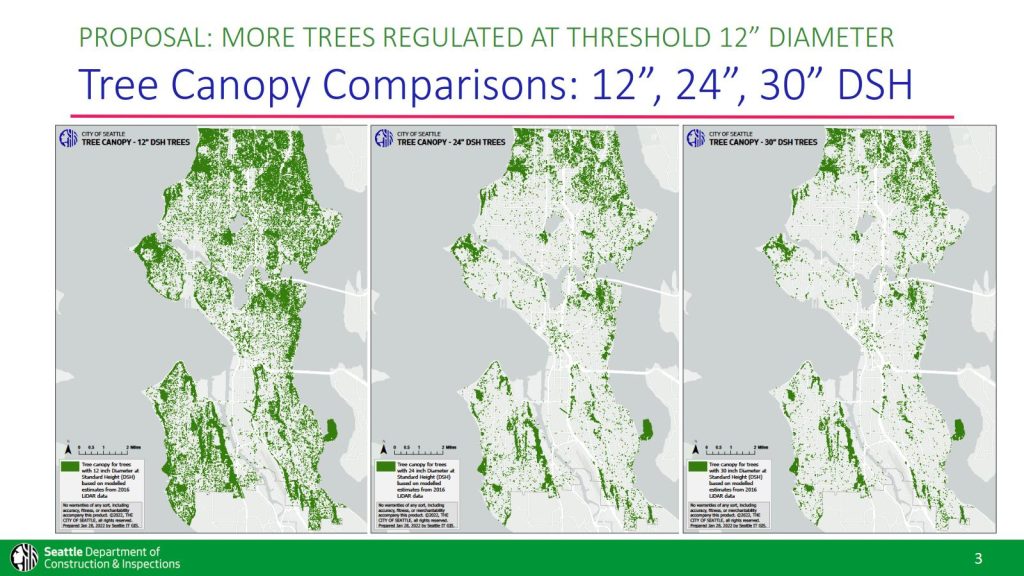

The legislation responds in part to a 2021 report from the city’s Office of Sustainability and Environment that found – using LiDAR scanning technology – that Seattle lost 255 acres of trees between 2016 and 2021, an area equivalent to the size of the surface of Green Lake. The report noted that 28% of Seattle is currently covered in tree canopy, and Strauss hopes his legislation will help the city meet its goal of 30% coverage by 2037.

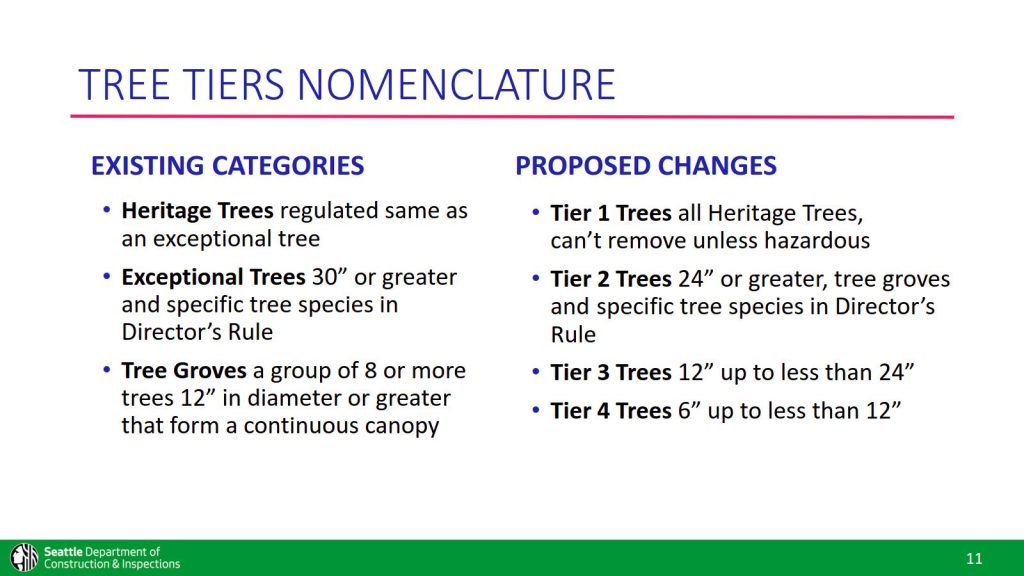

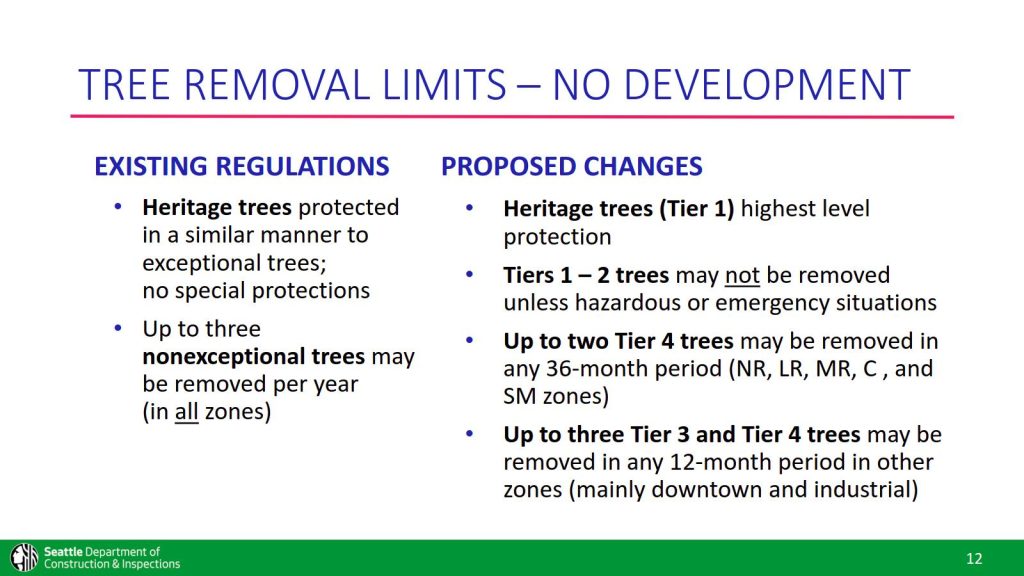

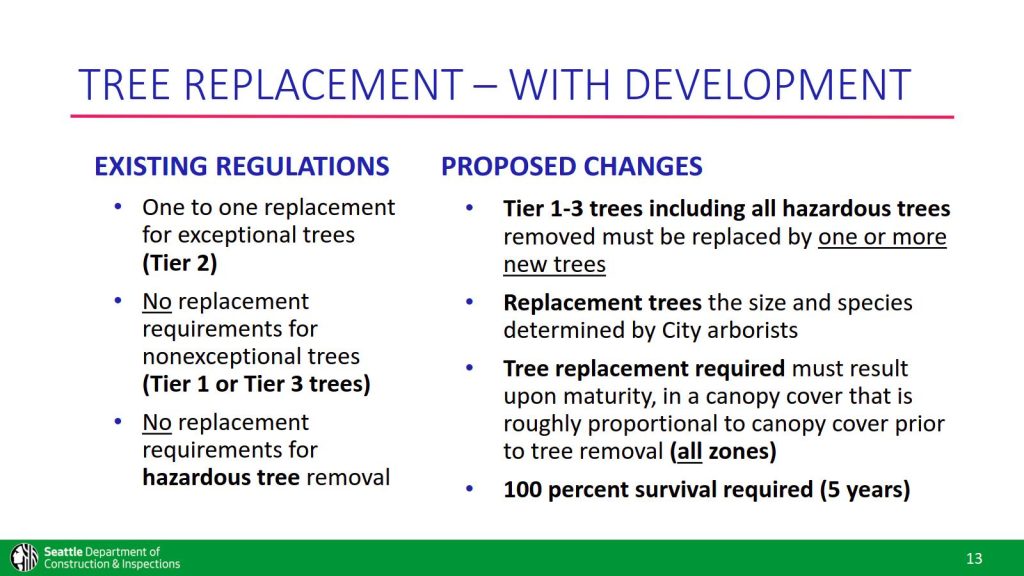

According to a presentation given by the Seattle Department of Construction & Inspections (SDCI) at Thursday’s committee meeting, Strauss’s bill makes a host of changes to existing law and increases protections for more than 70,000 city trees. It defines four new “tiers” of tree categories based on size and heritage status; generally prevents trees more than 24 inches in diameter from being cut down on a property that’s not being developed; requires one-to-one replacement of any trees removed that are 12 inches in diameter or greater; allows for some exceptions to the city’s setback and parking regulations to protect existing trees; creates an in-lieu payment option for developers who don’t want to do one-to-one replacement; and requires all new residential construction to include street trees in the right-of-way between sidewalks and roads.

Currently, the city only requires one-to-one replacement of trees 24 inches in diameter or larger, Strauss said.

“We’re experiencing a climate crisis,” Strauss said. “We know that trees clean our air, keep our homes cooler. If we plant more street trees, we’re going to cool down our concrete streets that are exacerbating our heat domes and heat events.”

Among its many provisions, the legislation re-categorizes trees by size. What were known previously as “heritage trees” (large and or historically significant trees) are now designated “tier 1,” and these can only be removed from a property if deemed hazardous by an arborist. “Tier 2” trees are 24 inches and larger, and on a property with no development, they may not be removed unless deemed hazardous. On properties being developed, tier 2 trees must be replaced one-to-one with a species that will eventually achieve the same canopy coverage, and the replacement tree must survive for at least five years.

Tier 3 trees are between 12” and 24” in diameter and are generally not allowed to be removed if no development occurs on a lot (there are exceptions for downtown and industrial areas). When a lot is being developed, all tier 3 trees removed must be replaced one-to-one.

Tier 4 trees are between 6 and 12 inches, and can be removed on property being developed. Where no development occurs, in most city zones, three tier 4 trees may be removed in a three-year period.

As an alternative, in some of these cases, a developer or homeowner can pay an in-lieu fee, which can run anywhere from $2,800 to upwards of $10,000, depending on the size of the tree.

As the above examples illustrate, the new regulations are complicated and can’t easily be summarized in a few paragraphs. Melissa Neher, director of American Institute of Architects (AIA) Seattle, says her organization is concerned about this complexity and uncertainties in the bill — for instance, a provision requiring the director of SDCI to determine which species of trees are acceptable replacements. She’s concerned that this and other paperwork could delay housing construction.

“We absolutely think that trees and housing can coexist and should coexist,” Neher said. “But our position is that housing is a human right. And the effect of this [bill] as proposed, would really increase the regulatory burden.”

Aliesha Ruiz, government affairs director for the Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish Counties (MBAKS), said the current version of the legislation is the most balanced she’s seen, though her organization is still concerned with the amount of discretion given to SDCI staff.

“Builders need predictability,” Ruiz said, noting that the rules are complicated and that this could discourage development. “Sometimes you’ll have a tree on a lot and they think they can either build around it or take it out, and then the reviewer changes that and then nothing can be done,” she said.

Ruiz worries “[developers] won’t build on a lot with a questionable tree because it’s not worth the risk. So you have to ask yourself: how many units are we losing every year?”

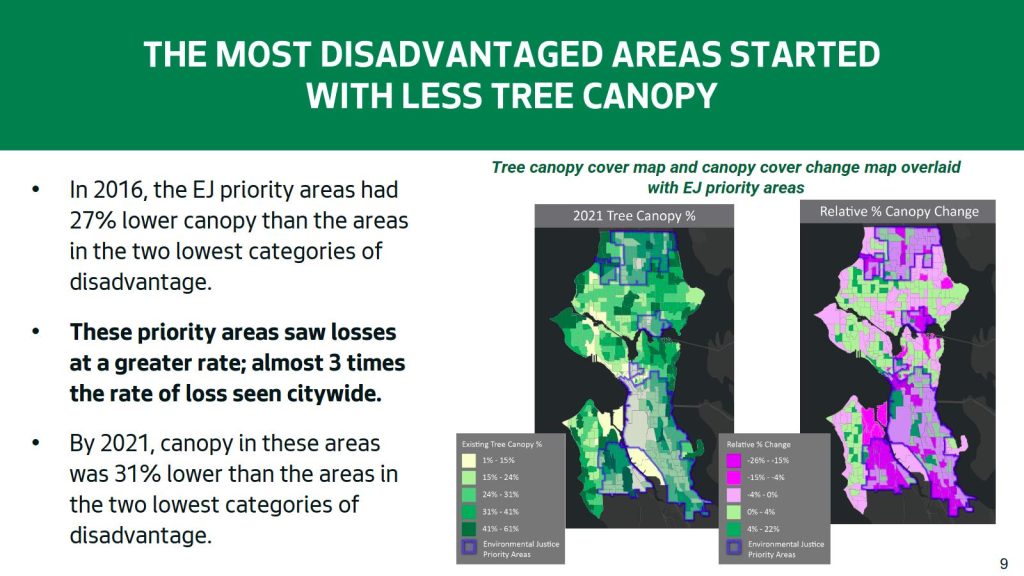

Tree advocates argue that the legislation is needed to slow the loss of tree canopy, especially in neighborhoods in the city’s South End, which the 2021 Tree Canopy Report found has been inequitably affected. “We know that people need an urban forest, and due to historical racist policies and practices like redlining, our urban forest is not currently providing benefits to everybody at the same level,” said Joshua Morris, urban conservation manager at Seattle Audubon and a member of the Urban Forestry Commission, “so the city wants to grow its canopy to 30% by 2037.”

By applying an environmental justice lens to tree canopy in Seattle, the report found that areas that were less advantaged in terms of racial and economic inequality had 28% less tree canopy and also faced 31% more tree loss.

One tool for dealing with this loss is the in-lieu fee, which could be used to plant trees in underserved areas. But SDCI calculates only about 1% of homeowners and developers will choose that option, resulting in a fairly modest annual estimated income of $191,000.

“Keeping the shift on preservation without looking at opportunities to expand canopy puts a lot of pressure on the development of housing,” said Neher, suggesting the city should focus more efforts on new trees.

In tandem with Strauss’s bill, Mayor Bruce Harrell issued an executive order aimed at increasing the city’s tree canopy, including a commitment to replacing every tree removed on city property with three new trees, and to replace all trees that die off from age or disease with an additional two trees.

On the issue of the in-lieu fee, Strauss is open to tinkering with the legislation, “I think [SDCI’s] analysis is strong,” he said. “Legislation is always an iterative process. So if changes need to be made, there’s always an opportunity to change.”

The issue of tree reservation is an emotional one in Seattle. In his opening remarks to the land use committee, SDCI director Nathan Torgelson noted, “In my long career with the city, I’ve gotten more emails on trees than on any other topic.” Tree advocates have pushed for years for a revision to Seattle’s policy, which will now more closely resemble Portland’s approach to urban forests, which was updated in 2021.

Activists went so far as to perform the infamous “Tree Murder Song” during a council session in early 2020. And the city’s recent removal of eight cherry trees near Pike Place Market by the city evoked a passionate outcry from some residents.

Without a doubt, urban trees provide numerous benefits — a 2017 Nature Conservancy report found that city trees mitigate summer temperatures, reduce air pollution, decrease stress levels, promote physical activity in children, and increase human immune system functioning.

But in a city where design review and zoning restrictions already lead to significant delays and cost pressure on the creation of new housing, Neher is concerned the added regulations will ultimately slow the pace of construction. “We’re looking at some of the vagaries of [the bill]: does this mean there are going to be significant increases in costs for every permit application, because there’s going to have to be an arborist report, detailed exhibits from the architects, review fee time, which ultimately is city staff time as well?”

Morris, of the Audubon Society, agrees these concerns are valid, but noted that the canopy report found that most tree loss wasn’t on newly developed land. “About 30% of canopy loss on our residential zones was attributable to a new development during the study period,” he said. “It’s something that we need to be careful about. Are we providing the right incentives to developers to be creative? Are we allowing enough flexibility in our design standards so they change designs to accommodate tree preservation?”

To that end, the legislation takes new approaches to site analysis, moving from floor area ratio (FAR) for multifamily and commercial development to a hardscape coverage standard equal to 85%, which would allow for more flexibility in site requirements if trees are left in place.

Strauss said that his bill allows for similar flexibility in site requirements such as setbacks if trees are protected. “There’s no reason that we need to have a concrete pathway required if it takes out a tree,” Strauss said. “Or if a building needs a certain setback and there’s a tree in the way? Remove the setback. It’s basic common sense.”

Because of the complexity of the measure and the emotional resonance with many city residents, Strauss has scheduled at least six land use committee meetings specifically dedicated to the tree ordinance before a final council vote in May.

Andrew Engelson

Andrew Engelson is an award-winning freelance journalist and editor with over 20 years of experience. Most recently serving as News Director/Deputy Assistant at the South Seattle Emerald, Andrew was also the founder and editor of Cascadia Magazine. His journalism, essays, and writing have appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, The Stranger, Crosscut, Real Change, Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Seattle Times, Washington Trails, and many other publications. He’s passionate about narrative journalism on a range of topics, including the environment, climate change, social justice, arts, culture, and science. He’s the winner of several first place awards from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.