The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has officially requested funds from the U.S. Department of Transportation to figure out how to plan and fund “low emission neighborhoods” in three areas of the city by 2028. The $1.5 million request was made via the Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity (RAISE) grant program, one of the most versatile transportation funding opportunities available for cities of all sizes.

Seattle’s request would enable the city to do a lot of verbs: “systematically plan, model, implement, and assess innovative solutions to the challenges and barriers facing our city and region in the quest to scale up to a low-emission and low vehicle miles traveled (VMT) transportation system,” according to the application, submitted earlier this year. But the request underscores a current dearth of shovel-ready, large-scale transportation projects that the city has been successful in securing funds for in the past via RAISE and its predecessor programs.

The plan to create low emission neighborhoods follows an executive order by Mayor Bruce Harrell late last year, following a visit to the C40 Cities Climate Leadership conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina. In 2017, Seattle, along with 11 other member C40 member cities, committed to ensuring that a “major area” of the city was emissions free by the year 2030. Seattle was the only U.S. city to join that pledge, along with cities that have gone on to rapidly implement and expand emissions controls like London and Oslo. Seattle’s commitment largely languished during the Durkan Administration, with an internal memo outlining potential projects representing the most progress that the city made during that time.

The Mayor’s executive order in December laid out the immediate steps that the city would be intending to take to restart the work within city government. “In 2023 this will include convening a community conversation aimed at planning low-pollution neighborhoods (like low-emissions zones, eco-districts, resilience districts and super blocks) that will align with the goals of the Seattle Transportation Plan and can inform investments in a future transportation funding package to replace the expiring Levy to Move Seattle (2024),” the order states.

“We’ve set an optimistic but achievable timeline to complete Planning work for the Low-Emission Neighborhoods project in 2025 and position ourselves for implementation by 2028, in accordance with our commitments to our local and national stakeholders,” SDOT’s new application for RAISE notes. It calls for SDOT to create a “Citywide Low-Emission Implementation Toolkit” by summer of 2024, create a “Investment Prioritization Framework” and select three neighborhoods for implementation by that fall, and fully develop concepts, and implementation and funding strategies by spring of 2025 to meet that 2028 goal of putting the projects in place.

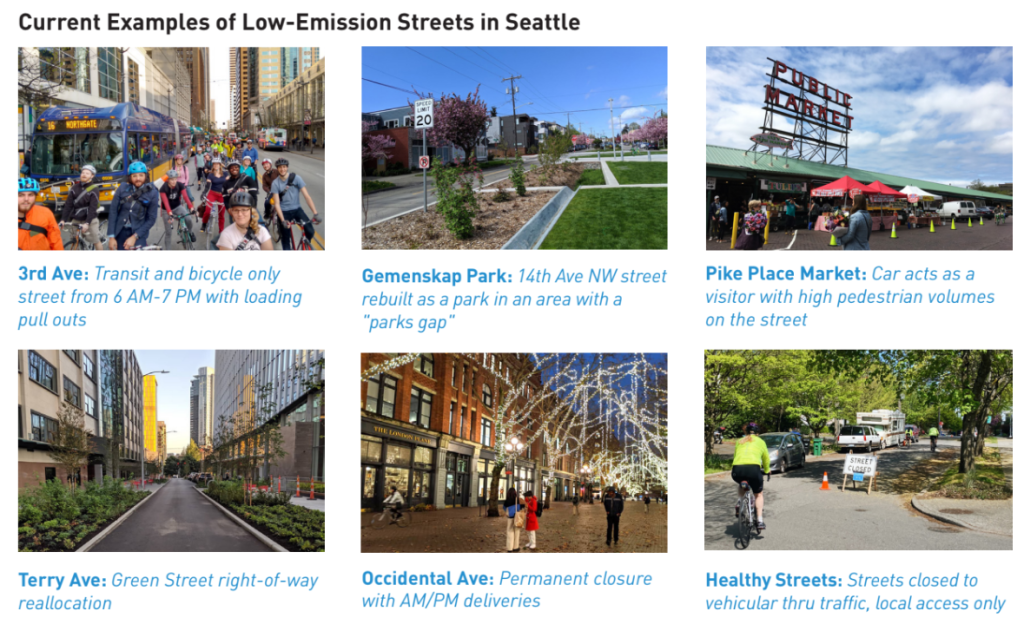

The RAISE application touts Seattle as being well-versed in the same tools that the city will need to implement these low-emission neighborhoods. “Seattle has several precedents where we have redesigned and reprioritized streets to support walking, biking, transit, and greening. We will build on these foundational efforts by working with community and industry to tailor plans for a holistic set of designs, incentives, and strategies that reduce transportation emissions and improve community health and resiliency in three neighborhoods,” it states. This is reiterated in the required “project readiness” component of the application: “The City of Seattle has established itself as a leader in climate action and is well-positioned to advance national and international initiatives for Low-Emission Neighborhoods through our networks with the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) and the international cohort of C40 Cities.”

But Seattle doesn’t actually have a well-established track record of effective general-purpose traffic controls, as evidenced by SDOT’s examples of low-emission streets as included in the proposal. All of the examples included — from 3rd Avenue downtown to Pike Place Market, to the pandemic-created Stay Healthy Streets–still allow private automobiles in varying degrees, making them all a far cry from Oslo’s Olav Vs gate, a brand-new pedestrian street in the middle of the city, to pick one example from elsewhere in the C40.

SDOT’s application to plan zero-emissions zones comes as the department has been removing signage for its Stay Healthy Streets program. The removals are from streets around the city where permanent infrastructure is not planned to be installed, including from a street directly in front of a middle school.

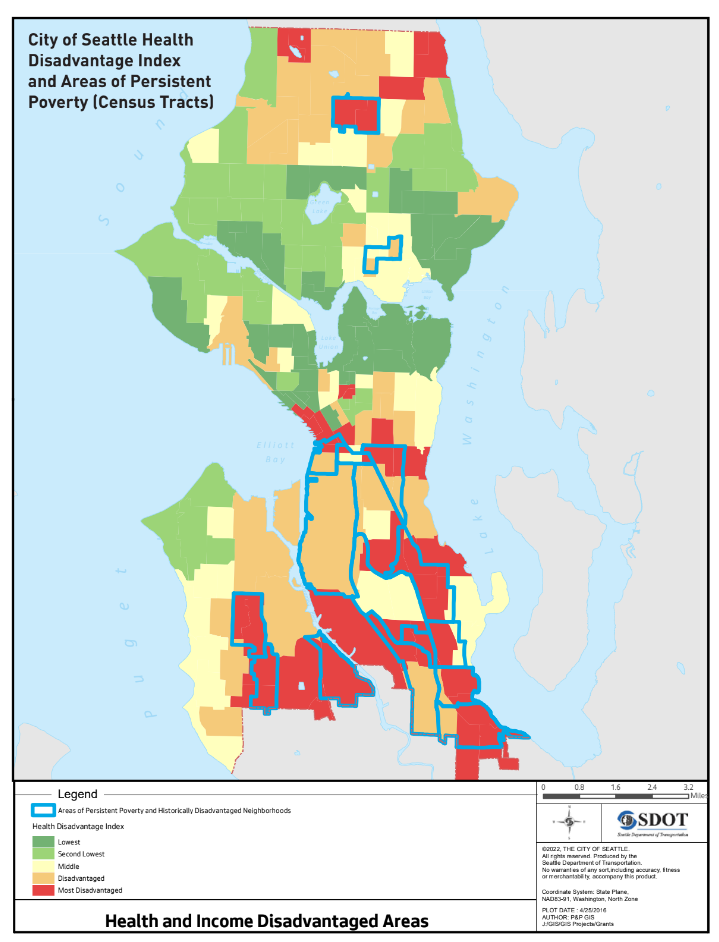

Does the RAISE grant application provide any clues as to which neighborhoods would be the first to see low-emission neighborhoods? Only insofar as it lays out how Seattle is planning to focus efforts on areas of the city where the burdens of emissions fall most heavily on residents. “By working hand-in-hand with community members, the City will seek to advance implementation of community-supported and context-sensitive solutions in those neighborhoods carrying the heaviest burdens today, per the City’s Health Disadvantage Index and Areas of Persistent Poverty, as defined by USDOT,” the application notes. It specifically cites the Duwamish Valley and its proximity to the manufacturing and industrial centers south of downtown. “Industrial pollution often blankets many of the commercial areas, inner-city neighborhoods, and cultural centers that make up Seattle’s core,” it says.

Passing on Construction Funding Opportunities

Seattle’s request for planning funds from the RAISE grant program represents the second year in a row that the City has not requested construction funding from USDOT despite a significant increase in available funds for the program thanks to the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law. Seattle did win a $20 million award in 2021 that allowed its street rebuild of East Marginal Way S to move forward, but in 2022 did not submit any grant application at all.

At the time, the city suggested that they were “likely not going to be competitive” for a RAISE grant based on the past success. However, an internal memo revealed that there were few projects that had been developed enough for the city to be able to go after federal funding, despite a lack of available funding early in the years of the Move Seattle levy leading to a scaling-back of many projects. Most notable, scaling back resulted in advancing only four out of the seven proposed RapidRide corridors promised to voters. The 2023 RAISE grant application criteria directly notes that past awards under the program do not impact current competitiveness.

Accessible Mount Baker, one of the more ambitious long-range projects that could make an impact on revamping some of the most dangerous streets in the city in Rainier Ave S and MLK Jr Way S, still appears to be languishing in the planning stage even as the city starts work on “near term” improvements promised to voters nearly eight years ago.

Late last year, Mayor Harrell’s budget proposal as sent to the Seattle City Council included a significant cut to the budget of a long-planned project to connect Climate Pledge Arena with bike facilities to the east through South Lake Union. Thomas Street Redefined, which would have constructed Seattle’s first protected intersection at Thomas Street and Dexter Avenue N, did not have its budget restored by the city council and now looks to have its scope scaled significantly back.

Seattle has shown it is incredibly competitive for federal grant dollars during this period of relative abundance, having been awarded the only implementation grant in Washington in the Safe Street and Roads for All Program during its first year in 2022, beating out other jurisdictions like Bellevue.

Regionally, other cities around Puget Sound have been successful in receiving awards, with both Lynnwood and Bothell receiving large construction grants last year for major transportation projects. Following the success of those mid-sized cities, jurisdictions like Shoreline are requesting funds this year in the hopes of being able to fill outstanding funding gaps on some of their biggest transportation priorities. This year, just like in 2022, those cities will not have to worry about competition from the City of Seattle.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.