This op-ed originally was published by the South Seattle Emerald.

On February 28th, 2001, I was in middle school, in the computer lab. I remember it vividly. Partway through class, our room started violently shaking. It felt like our school had been placed on top of a slab of cafeteria Jell-O, and someone was shaking the tray as hard as they could.

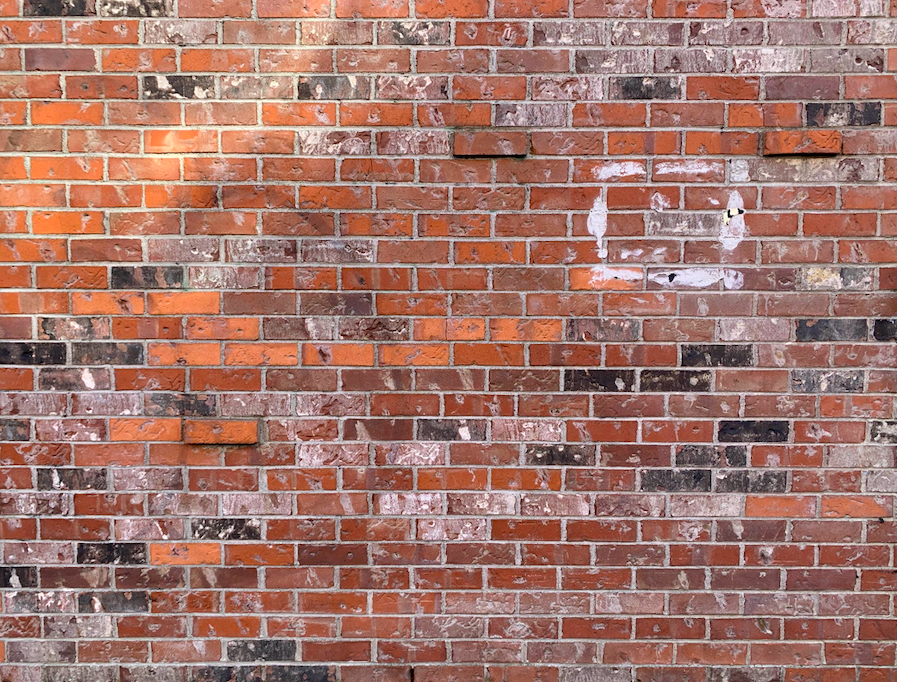

We dove underneath our desks as the building continued shaking, oscillating, back and forth and back and forth, for what seemed like a few minutes, but was actually only 45 seconds. Someone cracked a joke underneath the tables to lighten the mood. Others have told me stories about being in some of the old brick buildings in Seattle’s Pioneer Square, watching the floor beams rock in and out of the wall, hanging on by a thread.

After it stopped, we turned on the television. The magnitude 6.8 Nisqually earthquake had just struck Seattle, causing between $1 billion and $4 billion in damage. Thankfully no one at school was hurt. We lined up outside on the field and were let out early, with lingering uncertainty about a potential larger aftershock that never came.

Nine years later, I sat in Structures class at the University of Washington. The legendary professor Barry Onouye was at the chalkboard giving a lecture on seismic forces. We talked about why buildings collapsed in Haiti after a magnitude 7 quake (a rating of “major” on the Moment Magnitude Scale) had struck the island, leading to devastation and hundreds of thousands of deaths. Now, as architects in Washington State, we integrate seismic structural design and planning into everything we do.

Seattle’s next “big” earthquake will be significant. The city sits in the crosshairs of two perpendicular fault lines: the Cascadia Subduction Zone, along the coast of Washington, Oregon, and Vancouver Island, and the Seattle Fault, which runs directly underneath South Seattle. A third fault line of racial discrimination, segregation, and racially-motivated violence has set the stage to compound the damage.

Thousands of people live, work, eat, and play in buildings “especially dangerous, and prone to collapse in earthquakes” according to the City. Many were constructed using Unreinforced Masonry (URM). Yet, to date, the City has kicked the can down the road on what to do. One day, the City will kick the can off a cliff.

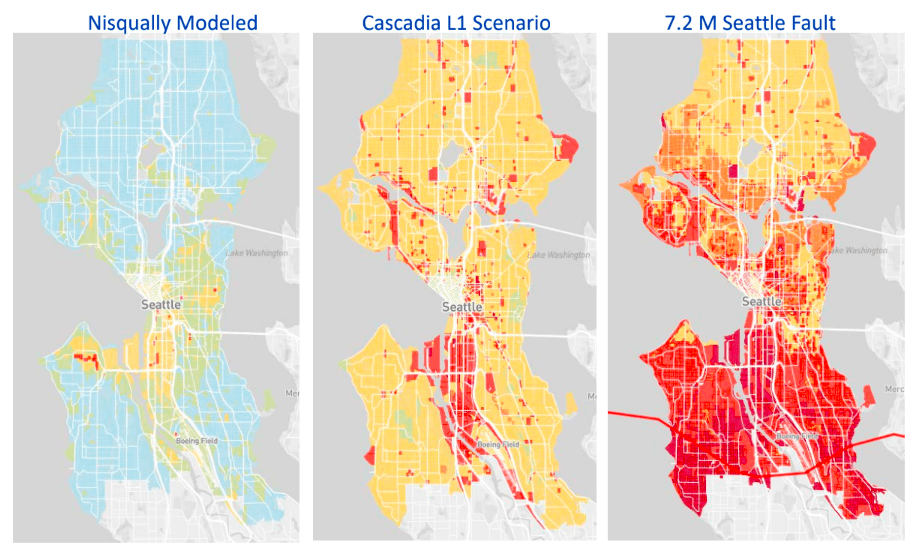

Who falls off the cliff, and who does the kicking, depends largely on the color of your skin and the money in your pockets. In 2020, Seattle’s Office of Emergency Management conducted a simulation of a big quake scenario. They found that, “Black residents were nearly twice as likely to live on a severely damaged block as white residents” in a Seattle Fault quake. In a Cascadia quake, low-income residents were 81% more likely than average to live on a block suffering severe structural damage.

The Mayor’s Office found that “Earthquakes, Seattle’s #1 disaster risk, have inequalities built in.” In essence, the City Government is internally planning for inequitable impacts, and has taken no legislative action to avert these projected impacts. Disparate impacts could be negated through clear policies and investments in building upgrades, education, outreach, and preparation, yet we have seen no action to make any concrete investments or to create legislation where it is needed. Pritzker Prize-winning architect Shigeru Ban emphatically stated that, “Earthquakes don’t kill people, buildings do.” Within Seattle, we have some killer buildings, apathetic policy, and decades of racially motivated land-use planning forming perfect crosshairs over South Seattle.

To understand how and why Seattle lawmakers don’t approach this problem with the same sense of urgency they show for junk police surveillance technologies like ShotSpotter, we must introspect into Seattle’s town legacy of de jure segregation and founding principles of white supremacy.

Seattle, since its town founding, has, through the law, explicitly excluded all other racial groups from the city — Indigenous people in 1865, Chinese people in 1882 and 1886, and restrictive covenants and policies including redlining, excluded Black, Asian, and Jewish people throughout the 20th century. Seattle police enforced, under the color of law, “sundown” laws in today’s wealthiest and whitest neighborhoods, such as Magnolia, forcibly removing and detaining Black men. In 1958, Seattle police refused to investigate a cross burning at a Black home in the U-District. To this day, Seattle police are under federal investigation and oversight for explicitly racially biased practices of policing. One SPD officer even told a colleague in 2020, “Well if I wasn’t racist before … I’m getting there now.” A former SPD cop called the City’s Race and Social Justice Initiative a “sickness infecting Seattle since 2005.” The violence and dispossession of minority groups, and specifically Seattle’s Black population, can be seen on a continuum.

Today, the compounding gap in generational wealth accumulation has reduced Seattle’s Black population’s buying power and increased Black homelessness to a rate four times that of their white peers. Evictions in King County also disproportionately target Black residents, “not simply due to lower incomes, but rather, it relates to the legacies of segregation that prevented many households of color from purchasing homes and participating in the building of the middle class through historical policies that subjugated and segregated Persons of Color. The dynamics of persistent urban segregation limits access to better neighborhoods, jobs, and class mobility and is reinforced through discrimination in housing access.”

Our next big earthquake will bring another overlay of violence to the city. Building damage can lead to building collapse. Rental agreements will be voided as buildings are severely damaged, leaving many without housing. Collapsed structures will cause injuries and possibly deaths, all with a predicted disproportionate impact again, to Seattle’s Black community. To understand this violence is to understand it as an extension and continuation of these state-sanctioned de jure segregation policies and state-sanctioned white-supremacist violence.

After the Quake: Disaster Gentrification

As we found with COVID, non-white racial groups suffer the most in a disaster. As we saw in the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, Black populations will even be maliciously targeted by white-collar scams that jeopardize economic, social, and housing security. As the City itself is predicting, Black residents will bear the overwhelming brunt of collapsed and damaged structures in the next big earthquake.

Anyone who has studied the history of the United States knows that it is on the ashes and ruins of structures inhabited by Indigenous people — by Black and Brown people — that our city and nation is built today. Seattle City leaders such as Charles Terry were even reported to have led the mobs of violent white supremacists razing and destroying the ancient dxʷdəwʔabš (Duwamish) village of həʔapus (ha-ah-poos). Terry would then donate the “Metropolitan Tract” to the University of Washington.

In 2021, the Los Angeles PD detonated a massive explosion in the middle of a formerly redlined Black and Brown neighborhood, causing significant displacement. In 1985, Philadelphia police detonated a bomb that destroyed 61 homes in a Black neighborhood, leaving 250 people homeless. Our history is full of whites firebombing and razing Black homes — under the color of law — in mobs or through racially motivated urban planning.

St. Louis demolished an entire black neighborhood to build the St. Louis Arch, driving displaced residents to Ferguson. New York’s Lincoln Center sits on the ground of a “Slum Clearance” project, which destroyed the vibrant San Juan Hill Puerto Rican neighborhood. Significant evidence suggests that a gentrification effort by Louisville developers led to the murderous raid on Breonna Taylor. After she was killed, the City and developers purchased the house she lived in for $1.

Our collective history of Black buildings razed to the ground by policies and state-sponsored violence shows that structural damage and collapse of Black buildings in Seattle after the next big quake can be understood as a continuation of that destructive structural racism.

Many in Seattle are aware of these trends. A coalition of community groups produced a 2021 report identifying the problem and called it by name: disaster gentrification, a practice where developers capitalize on disaster by buying property from vulnerable low-income residents and selling or renting it to people in a higher income bracket. In the report, the authors outline six concrete actions for policymakers to prevent it. Yet, none of these have been fully adopted by the City Council.

As the City contemplates updates to its Comprehensive Plan, up-zoning within South Seattle could cause property values to be worth millions more, increasing incentives for developers to target tenants and homeowners for predatory development.

After an earthquake, the City may require condemned buildings to be “demolished in a timely manner,” potentially leaving entire blocks of South Seattle as a billion-dollar greenfield development opportunity for the real estate industry, and thousands of Black and Brown families permanently displaced, faced with yet another lever of structural racism to bear against them.

The Mayor’s Office is well aware of the problem. Seattle deserves action to avert this looming crisis.

Glen Stellmacher (Guest Contributor)

Glen Stellmacher is a licensed architect. He is a graduate and former lecturer at the University of Washington. His work can be found around Seattle and in print within Advancing Wood Architecture: A Computational Approach, Trajectories, a compendium of research on robotics, digital design, fabrication and sustainable forestry practices and online.