A long-planned street revamp in downtown Seattle made headlines this month when a group of preservation advocates, many aligned with Pike Place Market, pushed back on the planned removal of two rows of cherry blossom trees across the street from the Market along Pike Street. The trees, which are nearing the end of their lifespan, were planned to be replaced with hybrid elm trees, intended to provide a robust tree canopy as they grow over the coming decades. However, the plan to remove the beloved trees drew criticism, in large part because the trees were seen as directly connected to the city’s history.

“Cherry blossom trees are more than a symbol – they invoke heartfelt feelings and represent decades of history – both the good and the bad – as part of our City’s deep connection to Japan,” Mayor Bruce Harrell said when he announced that the city would be reversing course, and will replace the current trees with new blossom trees. Eight new trees will be installed along the contested stretch of Pike Street and another 16 elsewhere in the city, possibly somewhere on the footprint of the waterfront redevelopment.

Removing the trees, which the City calls “in decline,” has been planned as part of the Pike Pine Streetscape Improvement project for several years, but their removal had escaped notice until the construction equipment was essentially in place to start work. The Pike Pine project extends from First Avenue all the way up to the foot of Capitol Hill.

But the episode obscures the work of biking and walking advocates who have been trying to influence the overall design of the project — and the block on Pike Street between First Avenue and Second Avenue in particular — for years with limited success. The work underway now, which will include some valuable and needed street upgrades to downtown streets, will leave many big opportunities on the table in terms of making the best use of some of the city’s most high profile public spaces.

This was exemplified with wide consternation at the wording of a March 4 tweet from The Seattle Times: “To make way for a bike and pedestrian corridor, eight cherry trees will be cut down.” In fact, the 100 block of Pike Street is the one area along the corridor where a set of two-way protected bike lanes are being removed in favor of a new curbless “shared street” where people riding bikes will need to share space with drivers using the street, and where new areas will be marked for loading. The most likely outcome is that cars will become parked anywhere there is room for them.

Brie Gyncild and David Seater are co-leaders with Central Seattle Greenways, and have been involved in the Pike Pine Streetscape project since its inception as “Pike Pine Renaissance: Act I” in early 2017. Few people in the city likely did more to push the city away from its concept of a curbless street, which had originally been envisioned for both Pike and Pine Street until the project’s budget scaled it back to just Pike Street.

Seater points to a requirement that Seattle Fire needed a large clear zone for its ladder truck as putting the kibosh on any bollards, and to the fact that parking stalls that could potentially be removed along First Avenue in the future for the Center City Connector streetcar as leading to the decision to add parking. But they both see the street as failing at what it was intended to do before it’s even built.

“Everybody thinks that a curbless street is somehow pedestrian friendly,” Gyncild told The Urbanist. “Without understanding that it’s not the curblessness that’s pedestrian friendly… curbs aren’t attacking pedestrians. It’s how you design the street that can make it pedestrian friendly.”

Seater notes that the decision to have no physical barrier between car space and pedestrian space, apart from the trees and lighting fixtures, will have consequences. “Most pedestrian curbless streets have bollards on them. If cars are going to be allowed there, they need to have defined spaces to go,” he said. “If a driver can put their car somewhere, they will. Especially without curbs, you need some kind of physical barrier to keep cars in their lane, literally.”

“Everybody wants to do curbless, everybody wants to do all-way-walk [pedestrian crossings]. There are all these things that are sexy, that sound good, and don’t necessarily work in every context,” Gyncild said. “I think if you actually stop and look at what you’re trying to achieve, and who’s going to use it, and how they’re going to be affected, you can come up with a much better design than just grabbing something off a shelf and saying ‘well, let’s do that.'”

But the wall of resistance at the city, and the Office of the Waterfront in particular, in influencing the design of the corridor project is not confined to its Pike Place Market end. Seater and Gyncild are even more frustrated with the way the project will be changing the configuration of downtown streets on the border of Capitol Hill. Where both Pike and Pine are both now two-way streets west of Bellevue Avenue, Pike will be reconfigured to be one-way eastbound and Pine westbound. But the conversation about potentially extending those one-way streets all the way to Broadway, which would be much more legible, hasn’t gone anywhere and the City doesn’t appear to be interested in restarting it.

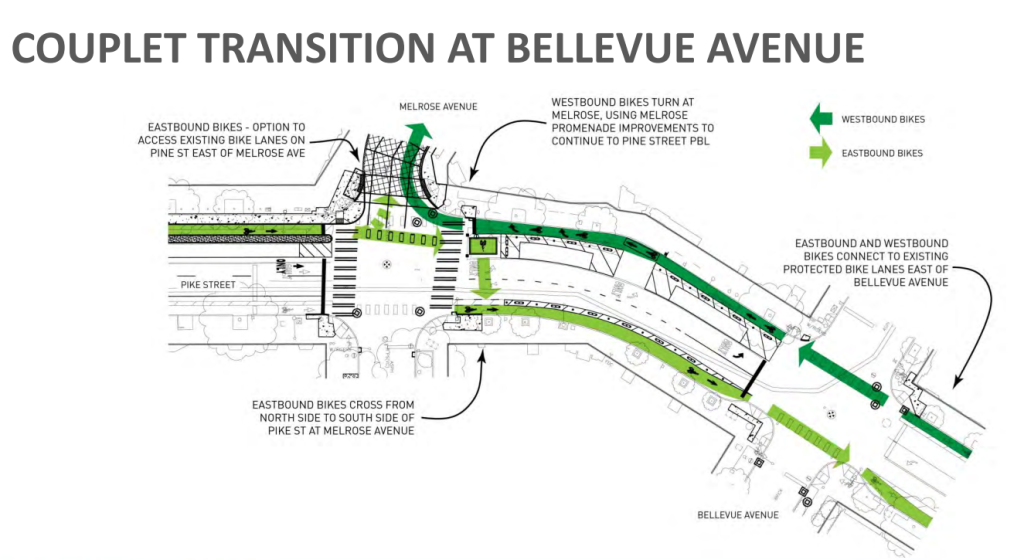

In practice, the configuration will put the safest bike route between Capitol Hill and downtown through an awkward transition at Melrose and Pike Street, with riders coming up the hill required to do a dangerous two-stage turn to switch sides of the street, and riders coming down the hill on Pike required to head over to Pine Street at Melrose. Central Seattle Greenways is concerned that people on bikes will not notice the transition point at all and will bike directly into oncoming bike traffic.

Meanwhile, an unrelated project, the Melrose Promenade, has created a mixing zone very similar to the one planned at Pike Place, with a brand new “raised crosswalk” in front of the Starbucks Roastery at Melrose and Pike. The design turns even more of the street into space for drivers without any barriers between car and pedestrian space. Due to the plans around extending the one-way streets, Melrose between Pike and Pine will become the official transition point for people on bikes travelling between Capitol Hill and Downtown, even though the lack of a barrier means the street will not be safe for people on bikes of any age or ability.

That transition would not be needed if the full street conversion was still on the table. “What we heard loud and clear from the community, was that it made a lot more sense to just go ahead and make both Pike and Pine one-way all the way up to Broadway. It’s a missed opportunity to not do that now, if you’re already changing all the streets up to Bellevue, you might as well do it all the way up to Broadway so people don’t have to adjust twice.” Gyncild said. “And it was a non-starter with the City, over and over again, and we never got clear information as to why.”

There are still outstanding questions around the way that the Melrose Promenade project was implemented, particularly how the raised crosswalk ended up not really being raised at all. But for Pike and Pine, Central Seattle Greenways will continue to push to make the most of the substantial investments. The project will finally bridge the incredibly unsafe gap for people biking around I-5 on either Pike or Pine Street, including eliminating the portion where cyclists are directed to use the sidewalk near the Convention Center. But for a full overhaul of two of downtown Seattle’s most important streets, the changes are not seen as achieving its full potential.

Gyncild notes that the primary focus of the upgrades to Pike and Pine was as a retail district enhancement, with mobility coming second. “Branding the entire thing as a pedestrian and bike project when it’s really not, has been really problematic,” she said. “It would be fantastic if it really had been.”

The last-minute change toward saving the beloved cherry trees, in the form of new ones, illustrates how the city is able to be responsive to pressure even as projects are heading toward construction. But when it comes to changes that could truly orient the project toward the goals and outcomes that are said to be the project’s main purpose, the city has been nowhere near as receptive.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.