Almost every single Monday or Tuesday night of 2023 has seen city councils in cities of all sizes across Washington meet with a common topic on agenda after agenda: House Bill 1110. The bill has become a lightning rod since its introduction at the beginning of this year. It would most impact cities — of any size — within the state’s biggest metro areas, raising the base level of allowed density on residential lots to four units, and six units close to the state’s most frequent transit lines. With most of these areas zoned for just one unit right now, low density residential areas would see a significant increase in zoned capacity, although analysis of the bill conducted in recent weeks suggests that increases in development will be modest and spread across the entire region.

Local city councils are spending quite a bit of time advocating against HB 1110, along with several other bills working their way through the legislature that would impact their ability to set local land use regulations. The arguments they’re using run the gamut. And all of them — go figure — come from the same baseline assumption that local land use decisions are best kept to jurisdictions of random sizes, with city councils whose members are, by and large, products of that same status quo.

Last night, HB 1110 passed the Washington House of Representatives by a wide margin, 75 to 21, suggesting that many of these arguments aren’t holding much water with lawmakers, but that might not be the case when it comes to the Washington Senate.

Not Enough Affordable Housing

Across the state, one of the most frequent talking points from local leaders in Democratic-leaning cities, is that statewide zoning changes don’t do anything to require that new units will be affordable to the people who most desperately need homes. One of the biggest advocates for this viewpoint has been Salim Nice, who has served on the Mercer Island City Council since 2017 and was elected Mayor by his colleagues in 2022.

“Mercer Island has consistently recognized the need for additional housing in our region,” he told the House appropriations committee in February. “In a time when Washington State is calling for one million new homes, half of which need to be affordable at 50% [area median income] and below, it’s disappointing that HB 1110 isn’t being positioned to deliver that affordable housing need.”

In early February, the Mercer Island City Council unanimously approved a letter opposing HB 1110, sent to the legislators who represent the 41st District where the city is located, Representatives Tana Senn and My-Linh Thai and Senator Lisa Wellman. “HB 1110, similar to legislation proposed last legislative session, is being marketed as an affordable housing bill to address the ‘missing middle,'” the letter stated. “This is a misnomer as the bill will produce almost exclusively market-rate housing. This means, especially in Mercer Island, that housing produced under this bill will be out of reach for low-and moderate-income families.”

In actuality, the “missing middle” refers to types of housing that would be allowed: duplexes, quadplexes, townhouses and cottage courtyard housing, that used to exist in many of the cities opposing HB 1110 but which they do not allow to be constructed now.

Even the town of Yarrow Point (pop. 1,125) near Bellevue, with an average home price of over $4 million according to data from Zillow, is using the argument that HB 1110 wouldn’t provide affordable housing, stretching the argument close to its breaking point. Yarrow Point’s mayor, Katy Kinney Harris, wrote to that city’s state legislators on March 2, asking for a no vote on HB 1110.

“The ‘supply’ created under HB 1110/SB 5190 will likely be completely taken up by market rate housing by the time affordable housing policies are implemented and the funding to construct affordable housing becomes available,” Kinney Harris said.

HB 1110 does include an affordability bonus, with up to six units permitted per lot on areas away from transit, if two of the units are affordable to renters of a certain income level. But the latest version of the bill also does not preclude cities from adding on additional affordability requirements. Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, requiring either on-site units be affordable or developers pay a fee create units off-site, will be allowed to continue and be applied to the new types of housing permitted under the bill. And many affordable housing providers themselves are supporting the bill.

“The types of projects that this bill will allow for, the types of homes that we at Habitat build: whether it’s quadplexes in Lake City, cottage housing for veterans in Pacific, and everywhere in between,” Ryan Donahue, chief advocacy officer at Habitat for Humanity Seattle-King and Kittitas Counties, he told the House appropriations committee. “These projects can be built in some specific, discreet areas today, but thanks to our outdated land use codes, even we at Habitat can’t build in something like 70 to 80% of our service area. If we want to build more homes — not just Habitat homes — but homes for all types of Washingtonians, we need to open up more land for more types of housing.”

But it looks like arguments like the ones Mercer Island is making are persuading some lawmakers.

“Washingtonians need affordable housing, and while HB 1110 should be commended on its goal to increase housing availability, unfortunately, it falls short in addressing affordability,” Rep. Senn said in a statement timed with the release of Mercer Island’s letter.

Senn succeeded in getting an amendment added to the bill Monday that would remove the requirement that cities automatically allow additional density near large parks and public schools. Another amendment she added to the bill will only require cities like Mercer Island (with fewer than 75,000 residents) to allow three units on most of its residential lots instead of the previous four.

Environmental Destruction

With Governor Jay Inslee coming out hard on the need to reform local land use to accommodate more housing, Edmonds City Councilmember Diane Buckshnis wrote the Governor in late February regarding the missing middle bill. “Your Presidential bid had one major platform of the impacts of Climate Change and yet, your discussions regarding housing do not address geomorphic events as they continue to be explosive and more frequent. So, I am asking you to be conscientious of the knowledge local lawmakers possess when it comes to zoning decisions and veto any bills regarding removing local control.”

Buckshnis, who was endorsed by Washington Sierra Club in 2019, does include a theoretical compromise. “Cities on a coastline or with major watershed(s) and the surrounding jurisdictions within a 15-mile radius would be exempt from any state mandate relating to zoning jurisdiction,” the letter suggests. This would make most of the state off-limits, particularly the most exclusive areas along the coasts.

In December, before HB 1110 was even filed, the Edmonds City Council adopted a resolution opposing any statewide laws preempting local zoning and land use decisions. “The Edmonds City Council opposes legislation, or other outside mandates, which changes or attempts to influence local zoning or building codes or any definitions associated with them,” the resolution states. It goes on: “The Edmonds City Council further resolves that, by its legislative policy, single family zoning will continue to be a component of our zoning codes.”

The Edmonds resolution succinctly summarizes its position that their existing local regulations are somehow best for the environment. “Edmonds is a waterfront community with a built-out city that has a unique topography with large watersheds and public spaces which limits our land capacity for new structures,” it states.

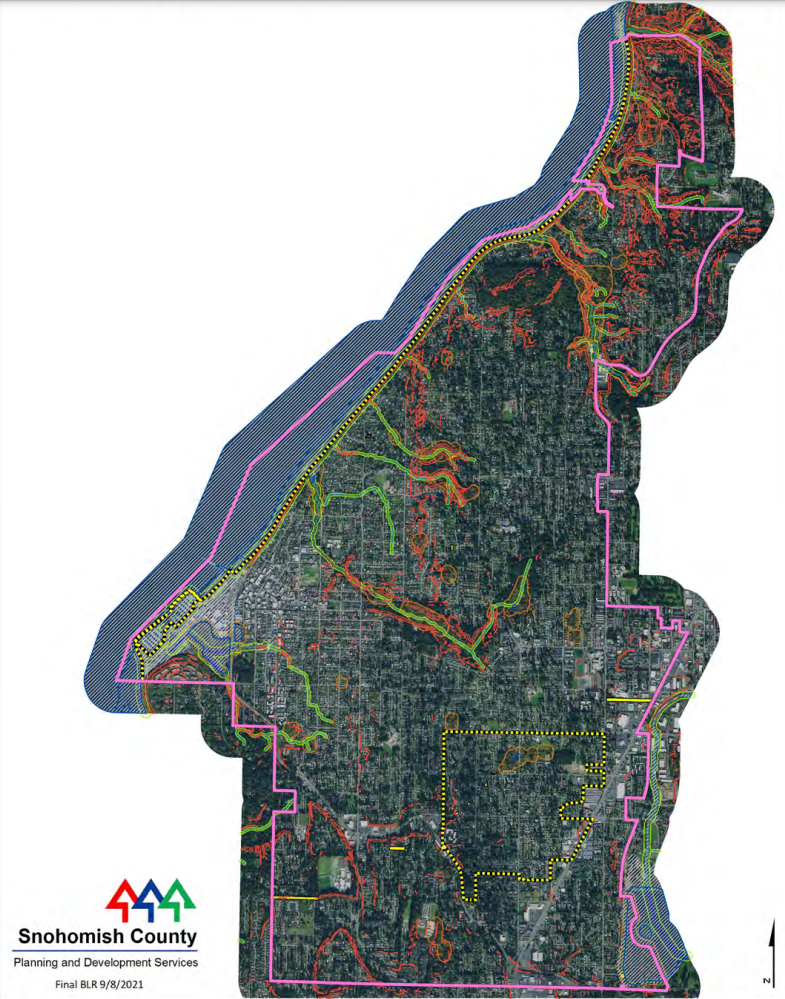

Critical areas and the buffers around them are already exempted from HB 1110: and large swaths of Edmonds are not actually within any critical area buffers. The city has made it pretty clear that it will be seeking to accommodate any anticipated population growth over the coming decades in a slim segment of the city alongside State Route 99, doubling down on policies that force new residents to bear the brunt of pollution, traffic violence, and the other externalities of a car-centric region so that the rest of Edmonds can be preserved. While it’s not unusual for a city to do this, it is not usually done so directly in the name of environmentalism.

The More Honest Answer: “Neighborhood Character”

Behind the litany of technical justifications that local officials are using to argue for maintaining local control, one argument surfaces most frequently and from many corners: “neighborhood character.”

“If you have a single family neighborhood, and your neighbor wants to sell the house…you could end up with a fourplex next to you if this bill passes,” Federal Way Mayor Jim Ferrell told his colleagues on the city council in late February. On the one hand, additional homes would be allowed to be built, a small step toward filling the anticipated need as Washington’s population continues to grow over the coming decades. On the other hand, you might have to see a slightly larger building next door.

Of course, “missing middle” housing types envisioned by HB 1110 generally blend right into neighborhoods, with many duplexes and fourplexes similar in scale to the larger single family homes being constructed in many of the region’s wealthiest cities. The mayor’s claim highlights that exclusivity is as much an element of “neighborhood character” as direct aesthetics.

“Thank you for taking the time to support the Town’s efforts to protect our neighborhood’s character and our local autonomy,” reads the call to email legislators from the city of Yarrow Point, getting straight to the point (so to speak), even as the mayor uses more complicated arguments in her letter to lawmakers. But the argument is incredibly widespread.

At a meeting in late January, members of the Bellevue City Council debated whether they should become the largest city in Washington to officially go on the record as opposing HB 1110. The city’s lobbyists in Olympia had been testifying as “other” on the bill, the same position as the Association of Washington Cities, in the hopes of prompting some concessions on the bill’s core provisions. In a long speech, Bellevue Deputy Mayor Jared Nieuwenhuis went through the laundry list of concerns the city had, including the ones noted above. But an exasperated Nieuwenhuis eventually got to the core of his argument.

“I’m just really concerned with the impact to the character of our neighborhoods,” he said. “Those people that have earned and saved, like myself, for many many years because I wanted to live in Bellevue but I couldn’t afford to live in Bellevue until I did everything I could to put myself in a position where I could finally get there…and then when I get there, I’m not sure I want a sixplex right beside me.”

Now that the bill is heading to the Senate, local governments will likely ramp up their advocacy against the bill. The Senate, having already passed its statewide transit-oriented development bill, may decide that the flimsy laundry list of reasons to oppose HB 1110 are enough and kill the legislation. Even as those arguments are simply standing in for the fact that local officials just don’t want their cities to change too much in service of the state’s pressing housing crisis.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.