In September of last year, Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) Director Greg Spotts took the megaphone at a rally of around 100 people on bikes at the Harbor Island site where Robb Mason had been killed while biking through a crosswalk three months prior. Spotts had been on the job for less than one month. He told the crowd, many of whom were mourning the loss of their friend and who were looking to the city for a response, that SDOT was taking steps to center safety inside its ranks.

“Vision Zero isn’t going to live in a little pocket of the organization any more,” Spotts told the crowd. “On my very first day on the job, I issued a call to action, to all of the senior people at SDOT that we need to do a top-to-bottom review of Vision Zero,” he said. “I know it’s easy to say we know what to do, but actually in government, with limited resources, we have to put those resources to the highest use and that has to be both data-driven and community informed.”

Now that review is over, and the resulting report has been released to the public. And it ultimately confirms that what Spotts said that night was true: the Vision Zero program indeed has been living in one little pocket of the Seattle Department of Transportation’s overall work. Despite all SDOT presentations starting with a rundown of the department’s vision and values, with safety near the top of the list, the report confirms many things stand in the way of safety improvements becoming fully embedded in everything that happens at the department. Some were broadly suspected, but getting the issues down on paper is a productive and valuable step.

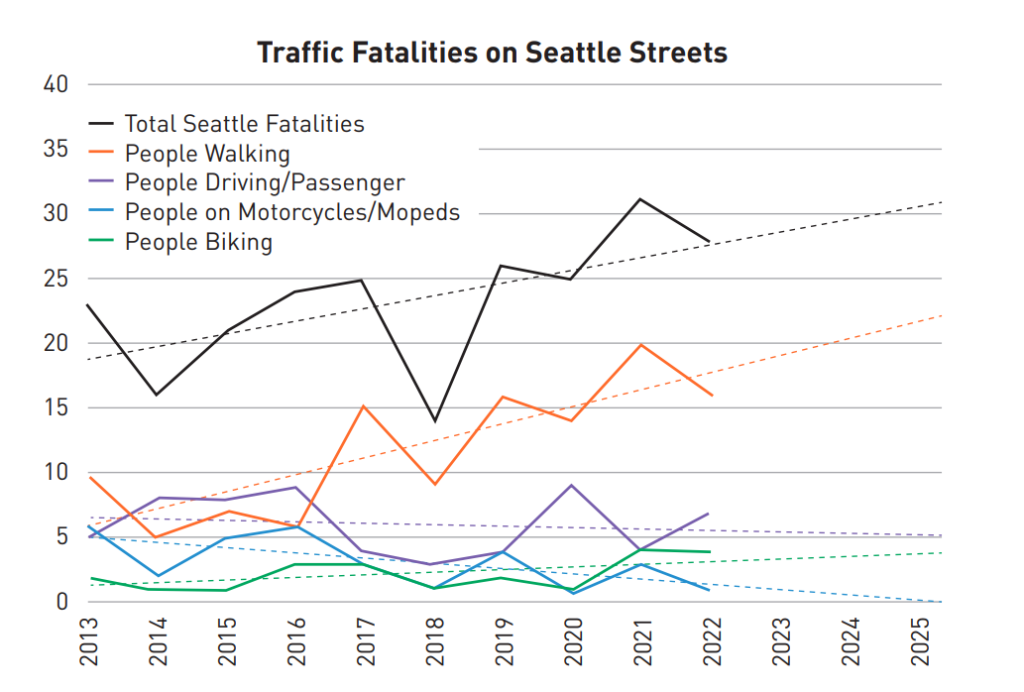

Ultimately the report doesn’t show the whole picture. It focuses on a relatively narrow range of projects where the department was able to make progress on safety, and not on two larger categories: opportunities where safety improvements were ineffective, and opportunities where safety improvement were not included at all. The report touts successes like the deployment of Leading Pedestrian Intervals: the tweaking of traffic signals to give pedestrians a short head start before a light turns green. However, the majority of the report ignores the broader question that the city as a whole is asking: why are serious injuries and fatalities increasing even as some of these treatments are working?

Insight into procedural barriers.

The report does offer a big opportunity for the general public to finally see what barriers exist to fully incorporating safety upgrades in the department’s daily work. On some of Seattle’s largest transportation projects, which represent the biggest potential gains for safety, cost impacts are cited as a major impediment to maximizing investment.

“When adequate funding is not identified to implement best Vision Zero practices as part of a capital project, SDOT does not have a consistent mechanism to plan for future improvements in that corridor or location,” the report notes. “In some cases, SDOT has phased improvements by implementing lower-cost improvements first and planning for upgrades over time. However, more often, improvements are not included in the capital project initially, or no plans are made for future additional improvements after lower-cost improvements are installed.”

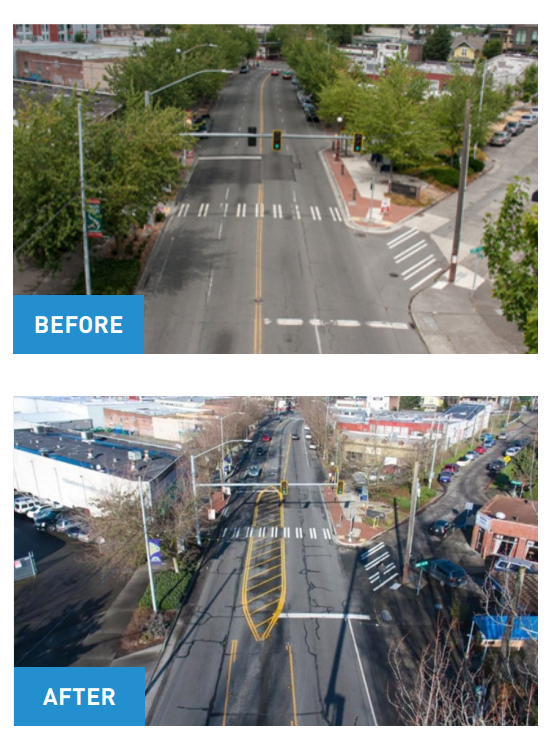

This is exemplified with the $16 million 15th Ave NW and Ballard Bridge repaving project. A “complete streets checklist” in the project’s planning document acknowledged the city’s vision for the street “encourages slower speeds and clearly communicates that walking, bicycling and transit access are prioritized,” and then completely skirted around the issue of making any improvements outside of the minimum legally required scope. After community groups sounded the alarm, Director Spotts announced that he was looking into ways to increase that scope. Since the director stepping in is not a systemic way to improve things, the top-to-bottom review notes that “SDOT staff are working on an ongoing basis to improve Complete Streets decision-making to right-size and clarify the internal decision pathways for specific types of issues.”

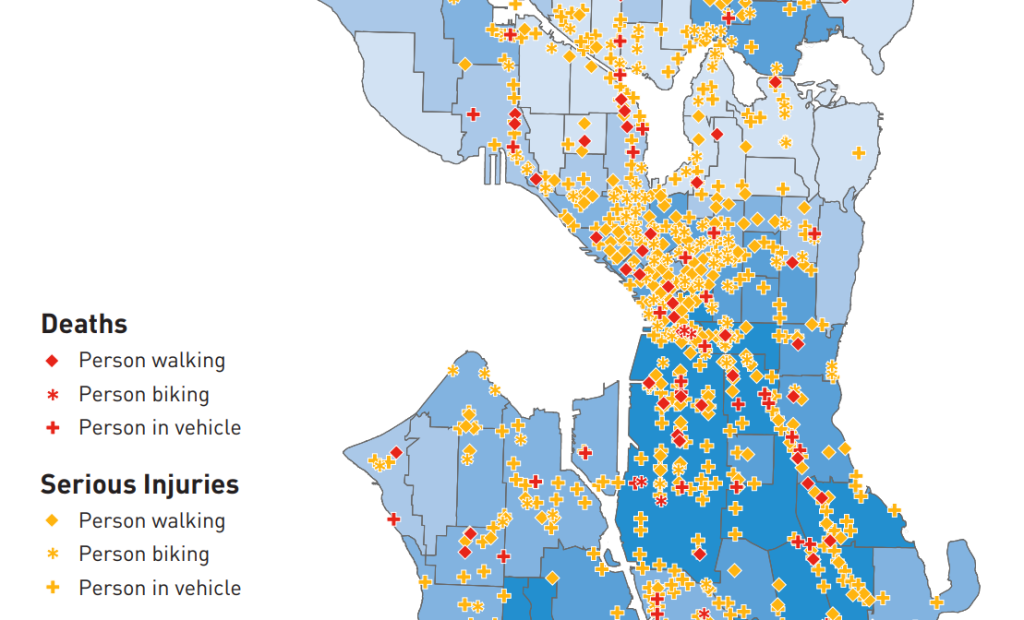

The report includes a map showing where fatal and serious injury crashes have occurred in the city since 2015, when the city first launched the Vision Zero program. While the data makes pretty clear where the most dangerous areas of the city are — wide arterial streets, particularly in South Seattle, and downtown — it’s minimally helpful in figuring out where safety interventions have been working. The city instituted multiple phases of improvements to Rainier Avenue, for example, implemented at different times. Clumped together in this analysis, it is impossible to move forward without knowing which were effective.

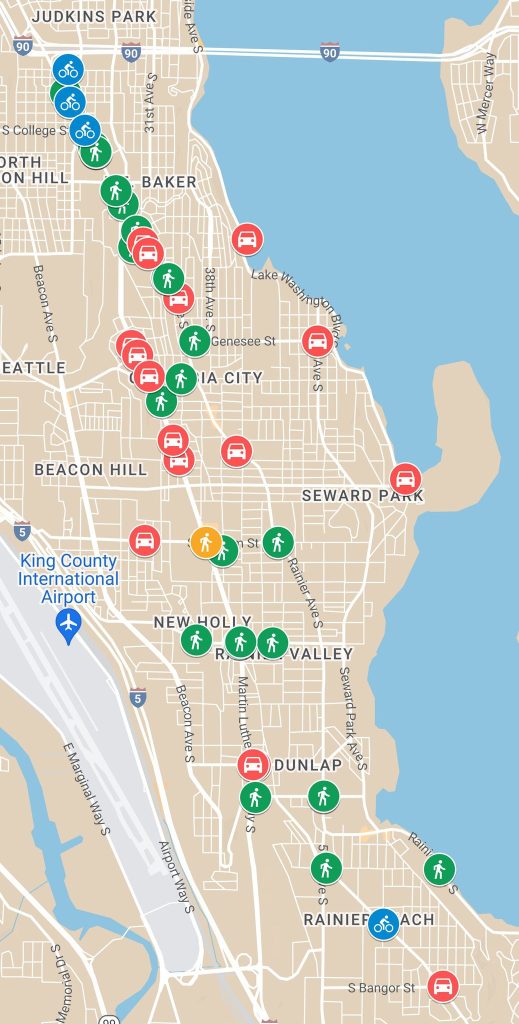

Rainier Valley Greenways, an advocacy group focused on improving safety and mobility in Southeast Seattle, created a different map, showing crashes that have occurred just since the start of the “top-to-bottom” review in early September 2022. The result, particularly along different segments of Rainier Avenue that have been treated very differently by the city, is stark. The map includes very few crashes on Rainier through Columbia City, where the city reduced the total number of lanes to improve safety in 2015.

But the report doesn’t really get into what the barriers — political, technical, or otherwise — would be to extending that successful treatment to other areas: higher traffic volumes on Rainier closer to I-90 and pushback from freight advocates would be at the top of the list.

Omitting lessons from unsuccessful changes.

One of the biggest missed opportunities in this report is a failure to look at strategies that have been deployed but haven’t worked. Incredibly, the impact of reducing the speed limit on nearly every arterial street in the city in 2019 and 2020, one of the most significant steps taken on safety during Mayor Jenny Durkan’s entire term in office, is completely evaded.

“We are rolling out a series of investments and changes we know will work to improve safety in our City and help all our residents feel safe getting where they need to go,” Durkan said when she announced the citywide speed limit reduction. But the top-to-bottom review focuses on the targeted speed limit changes that the department had been implementing in a few neighborhoods before that change.

“Data from 2018 to 2019 showed a 20 – 40 percent drop in the number of crashes in locations with new 25 MPH speed limit signs in study areas,” the report notes even as it declines to weigh in on what impact, if any, deploying that strategy citywide immediately after that had. Were the changes in traffic patterns from the pandemic so significant that they cancelled out any potential gains citywide? Did the gains on those specific streets also get erased? The city deserves a clear-eyed look at what happened so we can build on it, or not repeat our mistakes.

Mayor Harrell, who has primarily focused on issues other than transportation during his first year in office, lauded the release of the report. “This review and the concrete actions that follow reaffirm our One Seattle commitment to safety, as we work relentlessly to get back on track to reaching our Vision Zero goals,” he said in a statement following its release. But the limitations of the report were acknowledged elsewhere in city government.

Perhaps the highest-level elected official in city government interested in oversight of SDOT’s safety programs, Councilmember Tammy Morales, noted the review stops short of detailing how the department can rapidly scale up its deployment of strategies it knows are effective. Morales praised the department securing the United States Department of Transportation Safe Streets for All grant and the potential opportunities it represents.

“I am glad to see Director Greg Spotts and the department are committed to making a cultural shift to prioritize people’s safety where it has historically prioritized convenience for cars,” Morales wrote in a statement following the release of the report.

“At the same time, this report stops short of calling for dramatic or swift action to combat the unprecedented number of collisions, injuries, and fatalities on our streets, particularly in District 2,” Morales continued. “Changing signal timing and adding leading pedestrian intervals will not change the geometry of our streets, and as a result, will likely not change the behavior of users on these dangerous stretches of roadway. These actions are a start, but we need to fundamentally change our streets to address this crisis.”

Signs of hope.

With the report’s release, we now have a tidy list of one hundred actions that SDOT is set to internalize— hopefully. “Our recommendations place renewed focus on efforts to advance Vision Zero and are intended to provide an important input into SDOT’s upcoming update of the Vision Zero Action Plan,” the report’s authors note. But the real signs of hope that the culture is indeed shifting will come on the ground, in projects being implemented.

The “rapid response” changes that SDOT made along 4th Ave S in SoDo last year, in which the department did some outreach but primarily framed the changes as immediate ones that were intended to respond to the uptick of fatal crashes in the neighborhood, were noticed as a change in tactics by many in the transportation advocacy space. So too was the rapid deployment of a temporary bike lane in SoDo in response to an indefinite closure of the Spokane Street bridge. But ultimately these strategies can only aid in the culture change that the department is trying to foster if they’re broadly demonstrated to be effective, and (here’s the critical part) embraced by elected officials like the mayor and the entire city council.

And that gets to a core truth that we wouldn’t expect to be addressed in a five-month review: any strategies are only going to be effective if local leaders allow SDOT to try bold things, and not reserve safety treatments to only the instances where there’s little pushback. If they are, the city will find itself spinning its wheels indefinitely. And any report the department produces isn’t going to be enough to compel that to happen.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.