Seattle’s era of small thinking and smaller plans must come to an end. In order to face the combined climate and housing crises, the city and region must crawl out of its own navel and see the opportunities. This isn’t Burnham’s trope about making no small plans. This is moving past the immobilizing shock of the impossible moment we face and casting for ideas that have any hope of meeting the challenges.

Uncork the North End city center

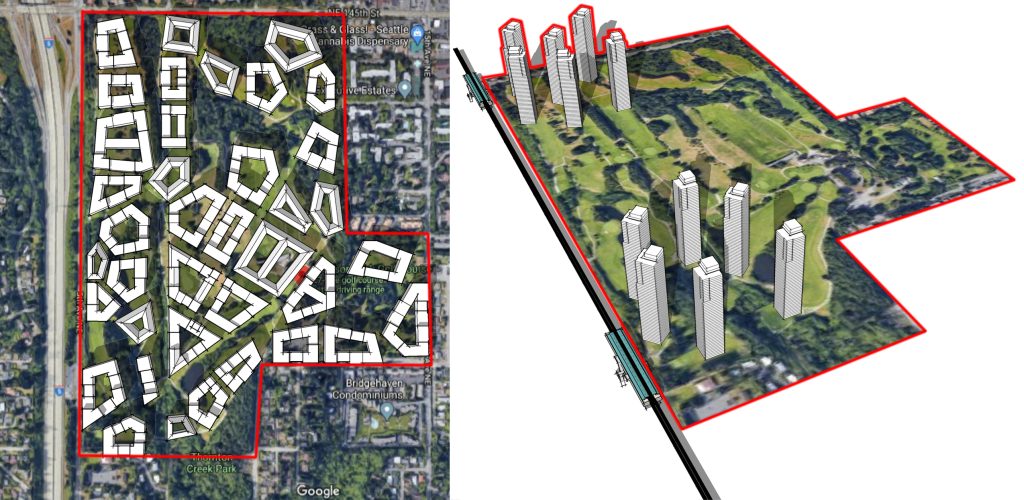

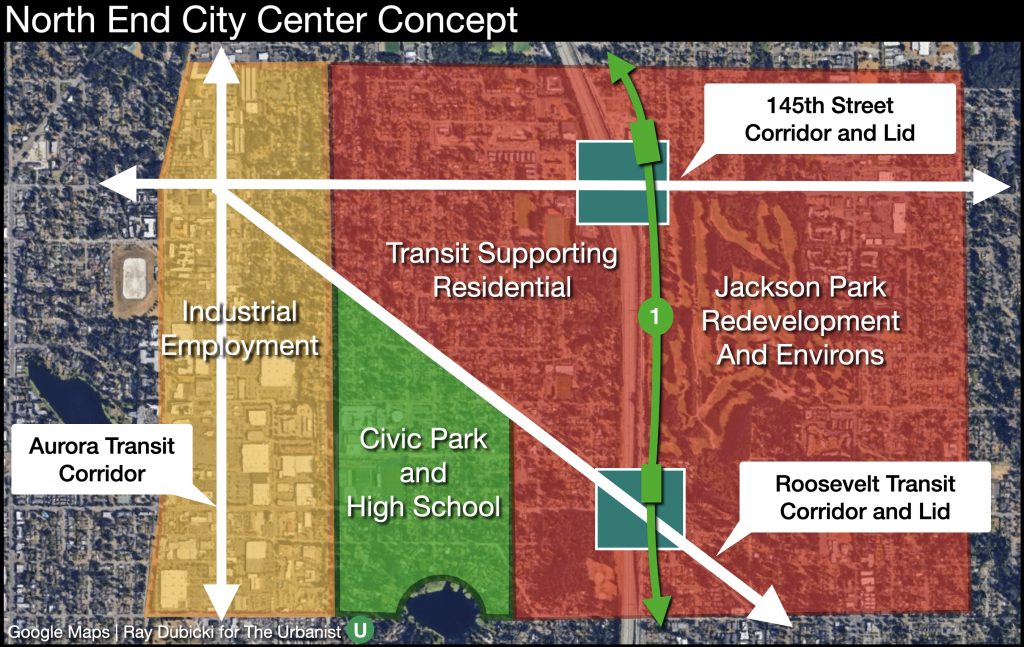

As light rail opens north of the quickly changing Northgate Station, focus is turning towards Jackson Park and the city’s northern edge. A number of proposals have cropped up for the golf course and its environs, including full redevelopment of the site and possible lids to reconnect Roosevelt Avenue over Interstate 5.

Casting slightly further west, the opportunity goes from big to megaproject. It is less than a mile to connect a light rail-centered Jackson Park redevelopment with opportunities on transit rich Aurora Avenue. At this location, Aurora is lined with large footprint, car-intensive commercial lots that can be consolidated into employment centers under Seattle’s new industrial zones. The two parallel corridors are just less than a mile apart. Combine the two, and it becomes a brand new urban center optimized with pedestrian focus.

Between the corridors is the low density neighborhood of Haller Lake. A generous estimate puts the area’s residential density at just over 3.5 units per acre, less than half what’s considered the baseline for frequent transit service. The area also includes a couple schools and some churches. As a latter annexation into Seattle, there are quite a few blocks without sidewalks. And it is getting some of the best transit being developed in the country.

To go big with rezoning and development in this area could add more than 60,000 homes, even if only built to Capitol Hill height. An industrial employment area along Aurora would be a third the size of Interbay, and with the right niche, could support 8,000 jobs. All that’s before deeply imagining the place as a new urban core. The terminal end of Roosevelt Way crosses the neighborhood diagonally, and could present a broad transit and pedestrian boulevard. Ingraham High School and its fields could be parts of a city center rather than exits off 130th Street. All of which could leverage burying the scar of Interstate 5 and connect with developments on Jackson Park.

The legality standing in the way here is Seattle’s noxious Initiative 42, a law passed by the voters in 1996 that bars selling park land without the city receiving “land or facility of equivalent or better size, value, location and usefulness in the vicinity.”

The last “and” here is problematic because it throws up a bar to trading the fenced, fee-based, underutilized Jackson Park golf course for well designed green spaces integrated in new communities. If the new spaces don’t check all four boxes of equivalent size, value, location, and usefulness, it doesn’t matter how used the new spaces will be, then the deal is off. Until Initiative 42 is amended to change “and” to “or,” it is a green space trojan horse hiding a climate suicide pact.

The bureaucratic bar is just as profound. The north border of 145th Street is a Washington State Department of Transportation surface highway as well as the boundary between Seattle and Shoreline, with King County responsibilities thrown in to boot. Just reconsidering the lanes of the road to make it slightly less of a deathtrap required extensive public consultations in two jurisdictions, and reams of interlocal agreements. Worse, Shoreline has already approved plans to increase density around the station, confined to their side of 145th Street. The road is not just a hard city line, it’s a barrier to imagination.

Overhaul heavy rail in the city.

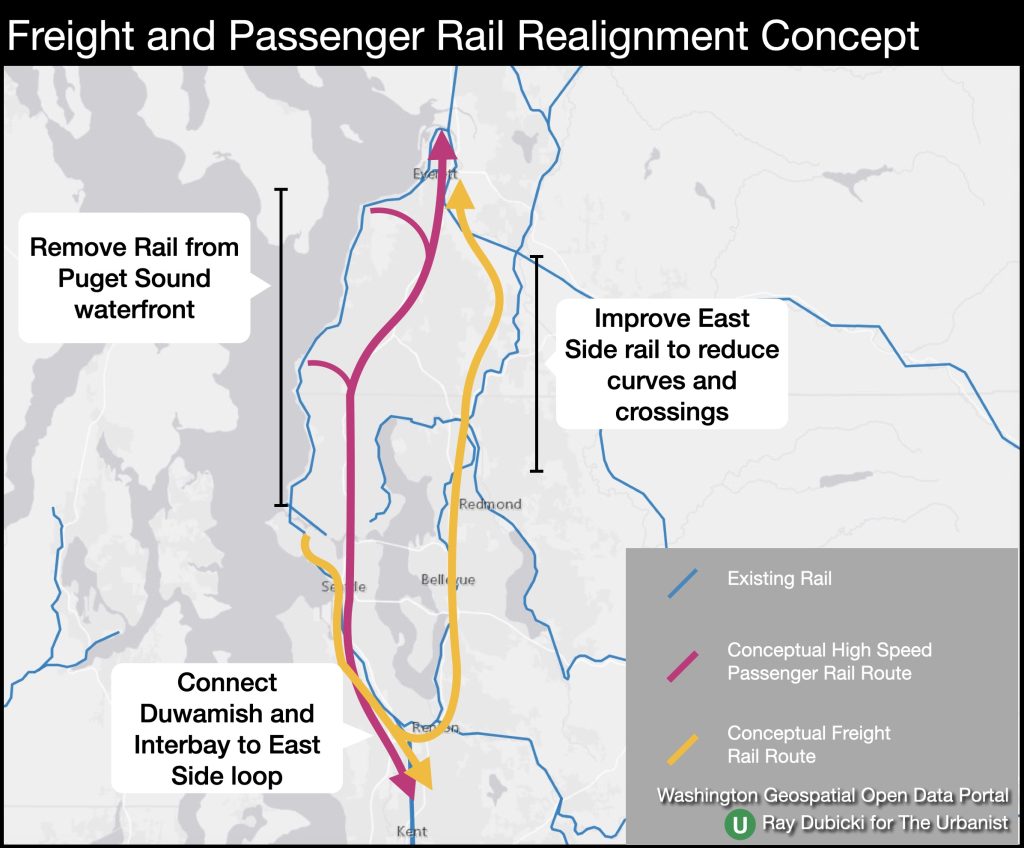

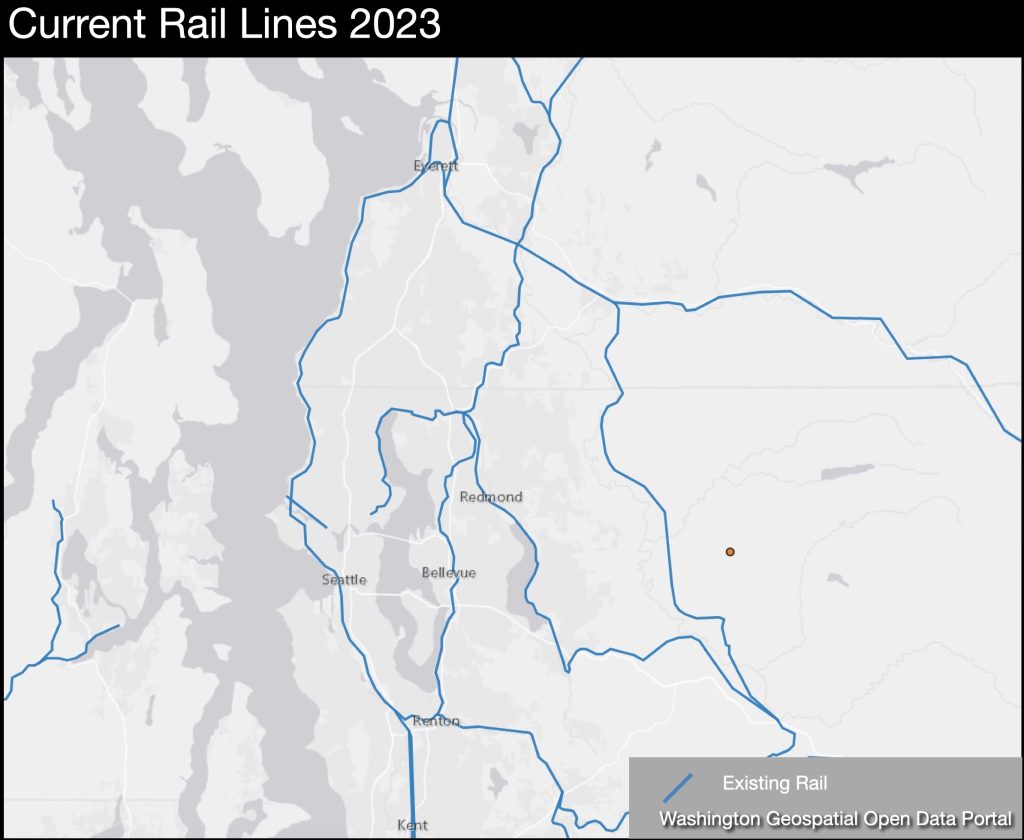

Trains in and out of Seattle depend on a thin line of beach along Puget Sound. Once trains cross the Salmon Bay Bridge and move north of the Ship Canal, they run at grade along the water until entering Everett. While mudslides onto the tracks have been infrequent for several years, the rising waters of the Sound present an existential threat to train routes.

Meanwhile, the industrial purposes of the system dwindle. There are no industrial users for the rail line between the Port of Everett and the Ship Canal. The Point Wells tank farm has been empty for three years. The rail yard in Interbay is subject to liquefaction and flood inundation, and the Port of Seattle’s new adjacent industrial park adjacent is being designed to face away from rail. And train derailments like in East Palestine, Ohio and Lac-Mégantic, Quebec show the danger of moving bomb trains through the city’s urban core. Every tank car with a 1267 placard is carrying crude oil under Seattle.

It is time to redesign Seattle’s heavy rail system. That needs to happen in two parts.

The first part is easy. Build a publicly owned passenger rail network. High speed rail was never going to happen on BNSF owned right-of-way because they have no incentive to build track that supports traffic over freight’s current 80 mph speed limit. So it’s imperative that the city and state get off their duffs and start acquiring the straight shot right-of-ways that are necessary to crank up the speed and not contend with freight delays and landslides. That means service from north to south AND east to west, spreading from downtown stations in Puget Sound’s largest cities to stops over the mountains and on the coast.

The second part involves far less visibility but far more difficulty. Preserving freight rail in the region is going to mean moving it inland. From Everett, trains could head directly south and wrap to the east side of Lake Washington before reconnecting with the existing lines in Renton. Trains to the Port of Seattle and the grain or maritime connections in Interbay can enter the city. As there are not oil depots in Seattle, the bomb trains would no longer need to go under downtown or past packed stadiums. Trains would also stop needing to roll across the Ship Canal and north Seattle’s entire coastline can be designated park land.

The primary barrier to any change is the train companies. Union Pacific and BNSF own Washington’s primary corridor rail lines, and they viciously guard their turf. Politicians are deferential to the companies, often because of the threats rail corporations make at the slightest whiff of not getting their own way, but also as owners of the land under the rails. For example, BNSF paid $224,000 in taxes to King County on just the northern portion of the Interbay rail yard in 2022, and that is a tiny fraction of the company’s overall holdings.

Redevelop King County International Airport.

Denver closed Stapleton airport when DIA opened in 1995 and has been redeveloping the site into a community of 30,000 homes. Chicago famously closed Meigs Field on the shores of Lake Michigan, or at least Mayor Daley did with bulldozers overnight in 2003. And Seattle already closed one airport when the Navy left Sand Point and the city converted the land to Magnuson Park. Perhaps it’s time to do it again.

With the region casting around for another airport location, it is time to take a hard look at the utility and future of King County International Airport/Boeing Field. Over 1.2 square miles of land in the Duwamish Valley, the airport hosts a central Boeing facility and 180,000 takeoffs and landings each year.

But those numbers can be misleading as a majority of flights are cargo, private planes, or short hops to Bozeman and Friday Harbor. And Boeing consistently shows itself to be a fickle neighbor. Whether it’s leeching the state for tax breaks or playing dance of the headquarters locations, Seattle should ask itself whether this is a group to be tethered to in the long term. Is it really worth giving up the city’s space for an airport to “frequently host celebrities, dignitaries, and sports teams” as the county’s website points out.

A redevelopment plan for the airport could break the site into four major parts. The north end adjacent to Georgetown would see fairly dense housing and amenities, taking gentrification pressure off the community. The north central part of the site should complement residences while maintaining industrial uses buy applying the city’s new Urban Industrial zoning which allows a mix of uses and local manufacturing. The bulk of the central airfield could reconnect the rail line along the east side with the Duwamish waterfront, one of the few places in the city where rail and water functionally meet. The remainder of the site could reflect the aerospace history and Boeing’s presence with the development of high-tech office space.

And consider the benefits. A quieter south end to the city without low flying aircraft. The possibility of a first ever east-west connection between South Park and Beacon Hill. A multitude of employers rather than a single too-big-to-argue behemoth. A future that doesn’t depend on continuing short hop flights everywhere.

The major barrier here is King County who released a high level economic impact study for the airport in 2021. Using the state’s Online Aviation Economic Impact Calculator, they figured that KCIA has almost $6 billion in impact on the community, a total of business revenues, jobs, and money pumped in by visitors. The number pollutes a lot of discussions about the airport, just as the airport does the surrounding community with noise and fumes. The report made no calculation for environmental impacts or public health.

The first and most difficult megaproject.

Just asking that an airport study make the slight recognition that airports aren’t great for everyone seems like small potatoes. But it’s really evidence of the most insidious roadblock to change. Agencies and groups throw up blinders to avoid hard questions and harder decisions. And that’s really what all these barriers are: self imposed silos. Initiative 42, jurisdictional boundaries, corporate governance and pointed “studies” that don’t ask real questions are all just rules and lines that were created by people and can be changed or removed by people.

While these three megaprojects may seem outlandish, they’re good illustrations of the mechanisms that get in the way of all plans in this town. The Urbanist covers a lot of development ideas, and reading through them shows most of the hurdles aren’t money or ideas, it’s the artificial barriers. They are siloed thinking wreaking havoc on even the most basic functions of government going on in Seattle today. We can’t get Sound Transit to talk with the Seattle Department of Transportation about working together on a bridge replacement. We can’t get Seattle Schools to coordinate with the City about building enough houses to keep from closing schools. All because of silos.

The most important generation defining megaproject in Seattle would actually be a demolition. Implode the silos. Erase those status quo blinders that keep good people from seeing outside of narrow lanes. Take down the barriers to communication between agencies. Dissolve the walls that prevent organizations from pooling their money to undertake bigger projects. Dismantle the ridiculous fiefdoms. It’s not nearly as sexy as a high speed train, but nothing is getting out of the station with all these barriers in the way.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.