The French Alpine town was offered a quirky alternative and turned it down.

Even in the United States, there was a point in the early 20th Century where most American cities and small towns had trains, trolleys, and interurban rail, often better than what is available today. It is a story that most people in North America are likely familiar with: the destruction of the trolley lines and replacement of them with large highways and arterial stroads.

What may come as a surprise to some is that this is not just an American issue. After the Second World War, numerous cities such as Paris, London, and Dublin abandoned their trolley or tram lines in the name of progress and modern infrastructure. Yet, within a few decades of their abandonment, one city helped kick-started the tramline revival in France and became a model for cities elsewhere. The small French alpine city of Grenoble brought back its tramlines, and teaches a lot by its example.

Welcome To the Alpine Train

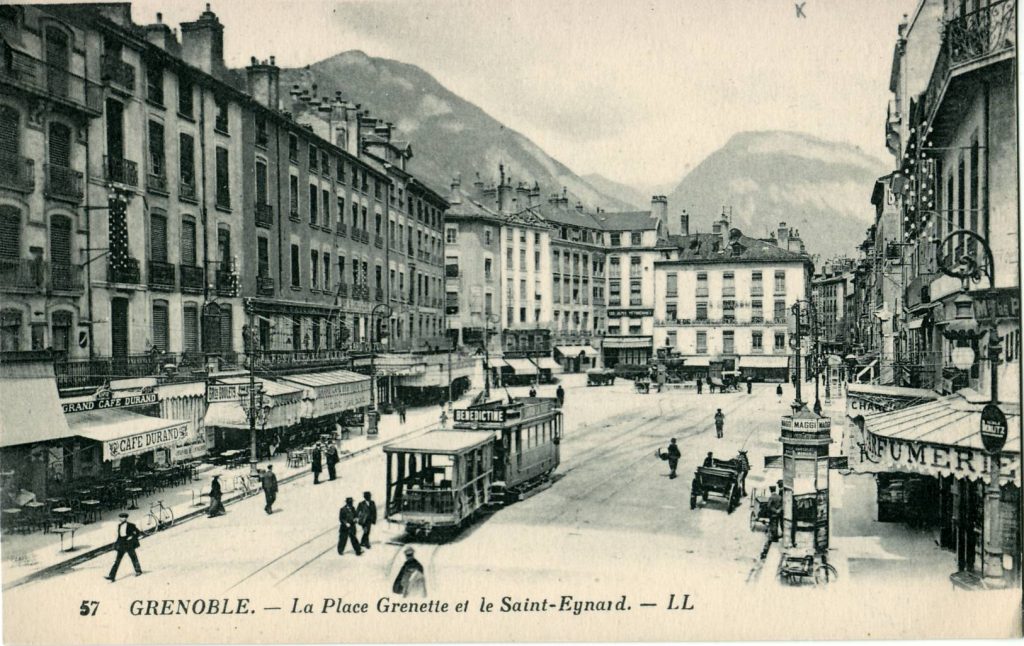

Grenoble, like most cities and towns in France, had a sprawling tram system for much of the 19th and 20th centuries. The first trams were horsedrawn before Thomas The Tank Engine-style mini steam locomotives took over and then electrified lines took hold. Impressively, Grenoble had more tram infrastructure by the end of the Belle Epoque than the current line, including the insane feat of a tramline going up the Massif du Vercors mountain range to connect villages up in the mountains.

While the lines of the city and its connectivity were impressive, the hardships which France faced in the first half of the 20th century meant that the city and the surrounding villages failed to keep up with the needed improvements to modernize the network. Grenoble was rocked by an ever changing economic situation from the end of the 19th century until 1945, including the decline of its historic glove-making industry, the loss of many locals as battlefield casualties in the First World War, the Great Depression, and then fascist occupation during the Second World War.

Following the war, France’s new government, the Fourth Republic, modernized its infrastructure. Nationwide, historic tramlines were ripped up and replaced by trolleybuses, buses, and cars instead of modernizing the fleet of trams, as they were considered obsolete.

In Grenoble, the combination of several factors lead to the dissolution of the tramlines in the city and the surrounding areas. Much of the rolling stock was old and obsolete compared to the newer and easier to aquire fleet of gas and trolley busses. Grenoble went on a series of building projects outside of its urban core inspired by a new generation of architects and urban planners. The main railroad was elevated above traffic to allow cars to pass under, and new suburbs and an American style university campus were built on the periphery of the city. While the tramlines could have been modernized, local policy makers at the time decided against it.

By 1952 Grenoble had ceased operating any of its old rolling stock and decided to replace the tram network with a fleet of modern trolleybuses with a greater carrying capacity. What trams were not scrapped were abandoned and left to rot. As the French economy began to rebound during the “three glorious decades” post-war, Grenoble grew. Car traffic became a bigger problem, peaking after the OPEC embargo in the 1970s. It was at this point a nearby cable car company proposed a gadget bahn to solve the traffic problem, the POMA 2000.

Enter the Gadget Bahn

The term gadget bahn was coined by Anton Dubrau in his urbanist blog. However, the term was popularized by civil engineer/ podcaster Justin Rozniak in his criticisms of the The Loop. A gadget bahn is a proposed fix to modern transportation issues with new transportation technology, usually proposed by private companies which will make a profit on the public infrastructure. Gadget bahns normally attempt to fill the same niches as trains and trams, but with varying degrees of success.

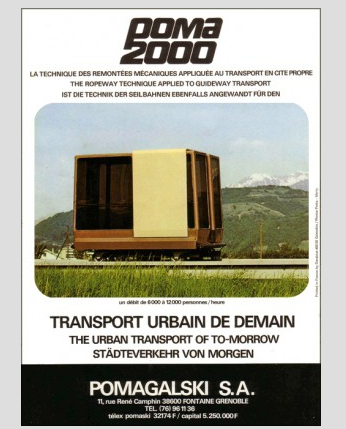

The POMA 2000 was an elevated transit system proposed by the nearby POMA cable car company which wanted to leave a mark on the city. At about 35 kilometers (20 miles) long with 83 proposed stops, the system was supposed to bring Grenoble into the future. It would have been an above ground towed cable car, and was supposed to be funded by the French government and the local metro area. The images of the proposed project and the test track are almost out of Disney’s Tomorrowland. Today though, the POMA is best remembered for being the gadget bahn which unwittingly helped spur the return of the tram to the Alps.

The most gadget bahn thing about POMA 2000 was that it never was built. The 1973 financial crisis led to cuts in the proposed budget. The POMA never got off the ground beyond a test track built on the city’s edges. The closest the line came to fruition was a smaller system built in the northern French city of Laon.

Beyond financial issues, the POMA cable car had other objections from locals. The proposed images of the project, which showed large above ground images of the cable car above the city, would have changed the cityscape. Additionally, while a cable car might make sense for the city’s mountainous surroundings (Grenoble has a small cable car built by the same company to a nearby park) the concept of a cable car in what is ironically one of the flattest cities in France aroused a negative reaction from locals. A reaction strong enough to rouse the memory of trams among many Grenoblois.

A Broad Social Movement for Trams

Public opinion mobilized behind the idea of bringing back the trams instead of chasing the POMA. A new group “ASSOCIATION POUR LE DÉVELOPPEMENT DES TRANSPORTS EN COMMUN” (ADTC) was formed in 1974 in reaction to the POMA. Made up of locals opposed to the proposed cable car, the ADTC championed improving public transit in the metro-area and organized around rebuilding tram lines throughout the city.

For more context, the tramlines would not have been made without a strong political and social support of local residents. During the 1970s there had been active political mobilization by the communist dominated suburbs to expand public transport over building more car infrastructure. While some local businesses and right wing political parties opposed the first proposed plans for bringing back the tram lines, a political coalition began to emerge involving the mayor, regional planners, neighborhood unions, supporters of public transit, and organized labor.

This coalition of support made planning for the tram focus on the social needs of the city. Even when the mayor changed, the new mayor turned out to be in favour of the tram system, but only with a referendum included. The fight for the tram culminated when the people of Grenoble voted by a narrow margin to bring back the trams in 1983. It was nearly a decade to get from the proposed cable car to a real tram line, and it had been a struggle, but the proponents of trams had won.

Finally, 35 years after the original teams of Grenoble were taken out of service, Line A debuted 1987, making Grenoble the second city in France to rebuild its tramlines. As for the POMA 2000, by this time, the idea was completely scrapped into the dustbin of history. The tram had beaten the cable car.

A Growing and Equitable System.

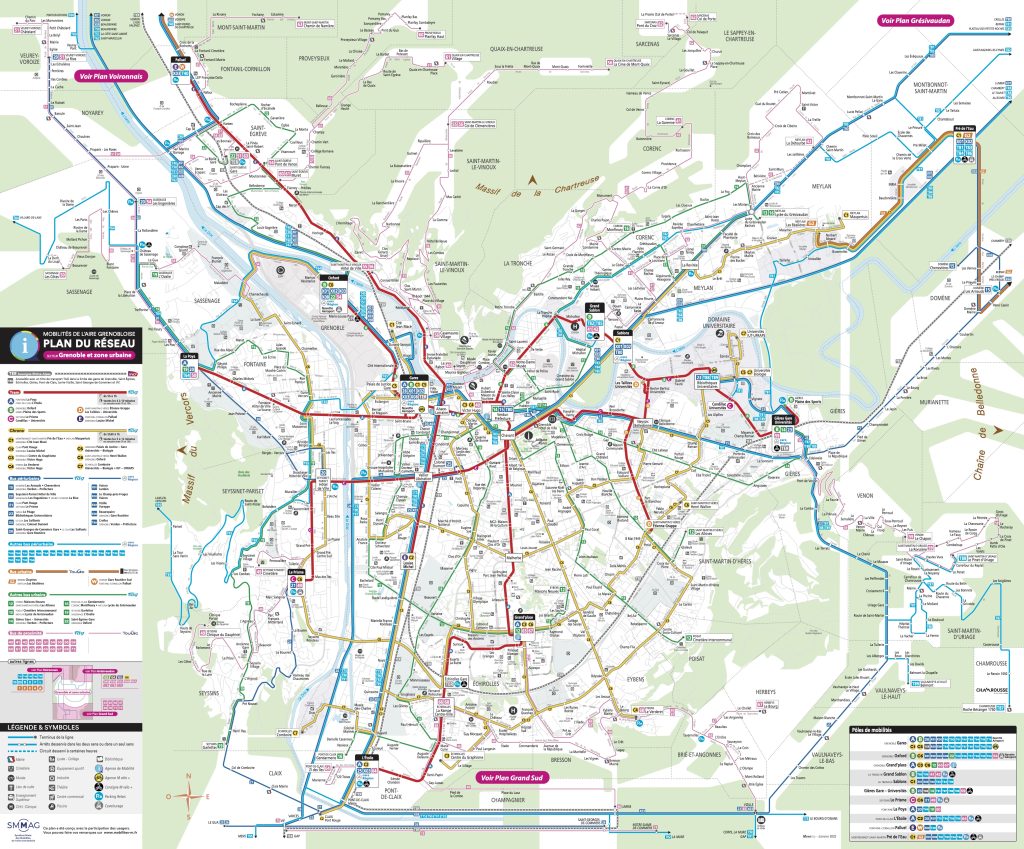

Grenoble’s tram renaissance could have ended with this underdog victory and become its own sort of gadget bahn. But it didn’t. The system is still growing. Since the original re-opening, four more lines — B, C, D and E — have been added with plans to extend the A Line further through the spine of the city. At about 40 kilometers long, the tram is much less than its heyday before WWI, but it’s still going strong.

The system connects the city to the nearby suburbs where the working class and middle class locals live and commute from everyday. The system was also built with beautification in mind. Fountains, wide pedestrian areas, cycle paths, and bus lanes are all adjacent or nearby the tram lines throughout the city. Additionally, TAG, the agency which manages the tramways, is planning on retiring the 1980s and 90s style tramcars and investing in new tram technology.

The system not only is well funded and supported, but the lines are interconnected to other parts of the transportation network. Most of the tram lines connect to each other at different points, as well as connecting to other modes of transit such as numerous citywide bus stops and three of the four train stations. (Hopefully Gare Pont de Claix will be added soon.) Additionally, when building the tramlines, city streets were re-designed to allow for less car traffic by reducing lanes for cars, turning some of the largest city highways into boulevards.

Another lovely feature about the tramlines in Grenoble was that early on there was a major focus on accessibility for everyone. The trams and platforms are wheelchair accessible and have been since the 80s. This is something not common in some networks in the US, as the urban planning YouTuber Alan Fisher showcased in a recent video essay on how un-accessible the trolley lines are in Philly. Grenoble solved the problem decades ago. It feels wonderful to see what a city would be like when designed for disabled people.

Further, exciting plans are in the works. There are plans to build an RER style transit system – Réseau Express Régional or commuter system – to expand service to the surrounding metro areas. It would do wonders for regional transit. There are also more plans to expand the tram lines around Grenoble- helping to extend the line to places outside of the immediate suburbs. (Also, I as a hiker would like the city to take up my request and rebuild the old tram line up a mountain plateau, please.) Regionally, a mountain railway which was set for closure was renovated because of the railway workers and the local communities fighting to save it.

As for the POMA 2000, the company has proposed plans to build a cable car from Massif Vercors into the business and research district, connecting parts of the city directly that previously have been cumbersome to reach. This too, however, has received much protest and opposition from locals. We will just have to see where the cable car goes, but I for one look forward to going anywhere in the Alps by tram and train.

Push for Tram Over the Pull of a Gadget Bahn

Grenoble shows a wonderful example of how an organized push for bringing back inter-urban rail, or even simply a better bus system, can be achieved. A highly organized movement of people can really force the issue, and can spur the need for better organizing on a grassroots level. The ADTC that began the movement are still around today.

Moreover, Grenoble showcases that building a comprehensive system over time is financially feasible, and that if built and implemented in a thoughtful way, people will ride public transit. Oftentimes it feels like what little public transportation that exists in the US is designed as a means of last resort. In Grenoble, it’s assumed to be for all. What is remarkable about the story of Grenoble’s tramway revival is that it could have easily not have happened. The city only voted for a tram line after much heavy political organizing from locals, planners, and politicians. It was a struggle to do, and in the end has been worth it.

The story of Grenoble’s tramlines is a story of a city rebuilding and rectifying an urban planning mistake. It’s a unique exception to what otherwise has been decades of neglect for public transportation throughout the western world. Not everything in France is as shimmering as a glittering croissant, but Grenoble’s transit system is at least a system urban planners in the US and Canada could learn from.

Sam Levitt

Based in France, Sam Levitt is an American writer who holds a Masters in History from University College Dublin. His love for hiking, urban planning and history has influenced his decision to live abroad and write along the way. Nestled in the French Alps with his wife and cat, Sam plans to expand his knowledge of Urban Planning by attending a local university in Fall 2023. His experiences living in the Czech Republic, Ireland and France have greatly impacted his perspective on urban planning. He enjoys a good pint of Guinness, talking about history with friends, and gardening.