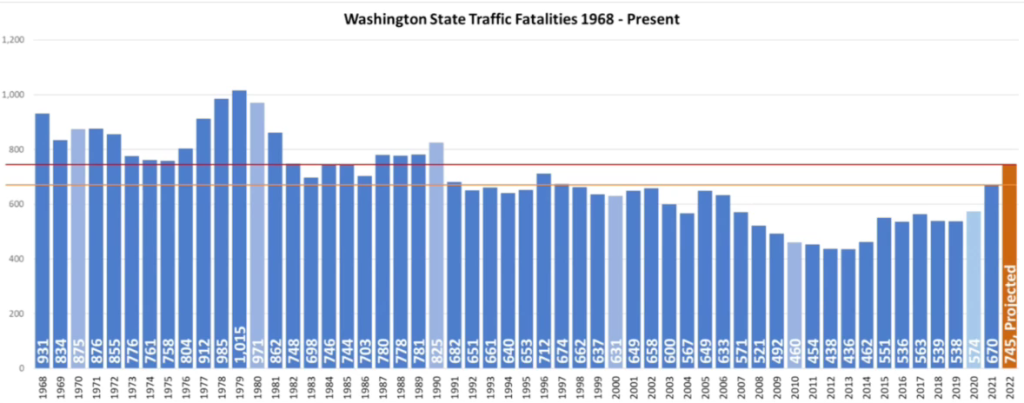

The Washington Traffic Safety Commission held a difficult conversation last week around its longstanding goal of ending fatalities and serious injuries in traffic by the year 2030: whether that goal has now slipped out of reach. Washington’s “Target Zero,” established in 2000, with Washington one of the very first states to commit to ending traffic deaths on any timeline, is drawing ever closer but for another year in a row, deaths on Washington’s roadways increased in 2022.

“For many many years it looked like we were going in the right direction, and it was very hopeful. At this point, we’re not going in the right direction, we’re going in the opposite direction,” Shelly Baldwin, director of the commission, told the commission’s other members, who all represent different sectors of state government in Washington: transportation, the judiciary, the state patrol, the governor’s office, and more.

Baldwin wanted to put the question on the table: should the commission consider extending the timeline for its goal of getting to zero traffic fatalities and serious injuries, or even remove a date from the goal entirely?

Early data presented to the commission, which uses a projection for the final month of 2022, showed 745 people statewide killed by traffic violence last year, the highest number since 1990. That number includes 122 people walking, anticipated to be a slight decline from the staggering 145 people killed while walking in Washington in 2021 but still much higher than numbers seen prior to 2020. It also includes 129 people driving motorcycles, which the commission was told was the highest number of fatal motorcycle crashes in state history.

There was not much appetite among the members of the commission to actually change the goal. But the fact that the conversation was even taking place was a striking turning point for the body.

“I feel strongly that we should not back off our aspirational date,” Sue Birch, Director of the Washington State Health Care Authority, said, instead suggesting that the commission should instead work with the Federal government to double down on its current strategy of relying heavily on educational campaigns, “focused on the intersection of behavioral health and driving.”

As to the role of infrastructure, Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) Secretary Roger Millar downplayed the role that the design of the state’s highway system has played in the dramatic increases in fatalities seen since 2020.

“The trajectory over the last three or four years is astounding. Now, the transportation network has not changed that much over the last three or four years,” Millar said. “So you can’t really blame the increase on the way we design and build highways. You can blame the horrific baseline we had in 2019, in part, on the way we design highways, and we own that.”

Millar’s analysis, however, sidesteps the issue of how most state highways, designed to maximize throughput, were poised to become more dangerous as dangerous activities increased statewide.

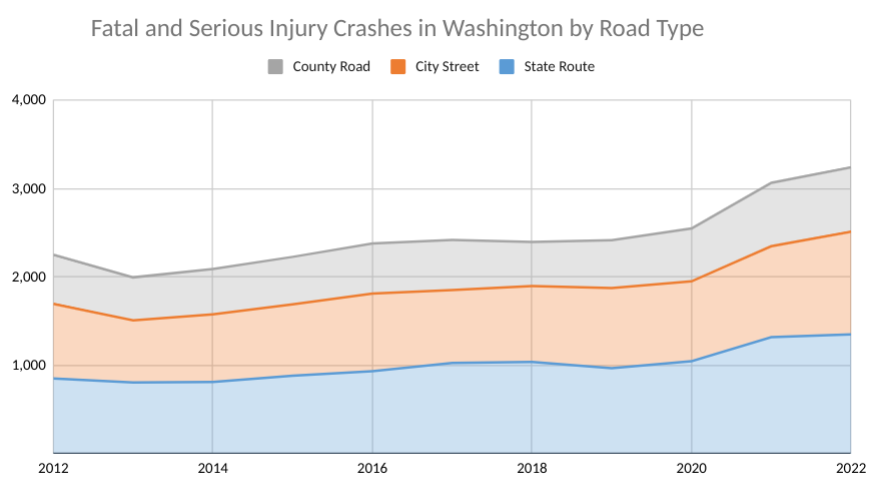

Preliminary data from last year shows that increases in fatal and serious crashes are being seen on both local roads and state highways alike. A decade ago, roughly 39% of the fatal and serious crashes in Washington occurred on state routes, compared to 41% over the past three years, a slight bump against a backdrop of an overall rate of increases of more than 25%. But state routes represent enormous opportunities to make gains on safety, with so many crashes concentrated on a small portion of Washington’s roadway network.

Millar pointed to legislative direction from the Move Ahead Washington transportation package that will require Washington’s transportation department to incorporate missing bike and pedestrian infrastructure, and infrastructure to lower vehicle speeds, into almost all of its highway maintenance projects, as a way that the agency is moving to address the state’s climbing crash rates. Last year, WSDOT noted that it’s expecting to be utilizing half of the $1.5 billion set aside in Move Ahead Washington for highway maintenance to add sidewalks, bike lanes, and speed controls to state highways, but those infrastructure changes will be gradual and not necessarily tied to the most crash-prone locations.

Millar also seemed to push back on the commission’s longtime focus on messaging campaigns: “PSAs are great but…this commission needs to think about the things that can be done, that are going to make people uncomfortable, that are going to be heavy lifts.”

He pointed to the bill, proposed by Senator John Lovick (D-44, Mill Creek), that would change Washington’s threshold for charging a Driving Under the Influence (DUI) offense from 0.08% to 0.05%. Utah, where a similar law took effect in 2019, saw a double-digit drop in traffic fatalities that year without a commensurate rise in DUI-related arrests. He also brought up driver’s license re-examination, which has been a bit of a third rail in traffic safety discussions for a long time.

In the 2023 legislative session, there does seem to be a large amount of energy to examine how to improve driver behavior, but that energy will likely wane the more drivers in Washington are impacted by potential changes.

“This is the time to be bold. I know we have the attention of the legislature,” Debbie Driver, representative from Governor Jay Inslee’s office, said. The Governor’s proposed budget includes $5 million for WSDOT to be able to respond to urgent safety needs as they arise, most frequently following a high-profile crash. Traditionally enforcement or education, and not infrastructure changes, have been a go-to when elected leaders want to demonstrate they are taking the issue of traffic safety seriously.

“I don’t want to lose the motivation we have,” Driver said. “Changing the Vision Zero right now might lessen the attention we’re receiving and the importance of our message.”

If past events are any guide, the efforts expended this year to improve safety won’t go as far as what is needed to to get Washington on the right track toward dramatically decreasing the number of people seriously injured and killed on the state’s roadways. Any elements of the all-of-the-above strategy that can get us closer, though, will be worthwhile. But it’s not clear how much the state’s Target Zero goal, now in its third decade, will have had to do with any progress.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.