The bloody saga of the Burke-Gilman Trail’s Missing Link never seems to end, and the latest disappointment in this odyssey involves treacherous gravel pits. Ironically, the gravel was intended to make the trail safer by forcing riders to perpendicularly cross railroad tracks in a particularly troublesome section just east of the Ballard Bridge underpass. Through the installation, the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) was attempting to meet (in its own way) a legal settlement requiring them to improve conditions.

Last Thursday, Seattle Bike Blog‘s Tom Fucoloro published a critique of the new design, which confirms (along with comments on the story and social media) that the change was not well received.

“SDOT completed work on an ‘interim’ redesign of the problematic track crossing under the Ballard Bridge for people attempting to bike the Missing Link of the Burke-Gilman Trail, but the new gravel pits sporadically placed in the area seems to be baffling riders rather than helping them,” Fucoloro wrote.

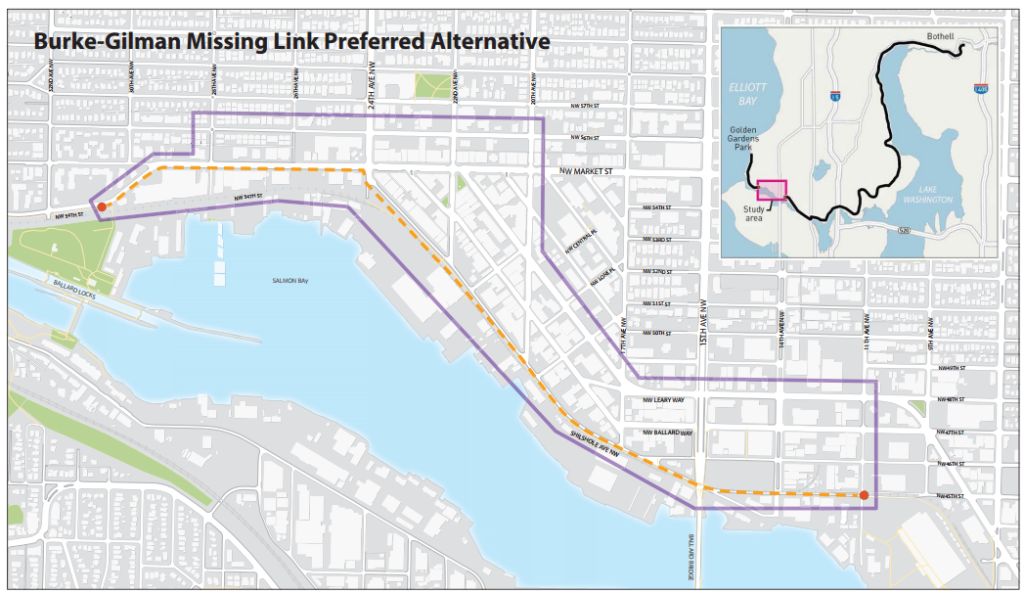

The long Missing Link saga

Fucoloro has closely covered the decades-long Burke-Gilman Trail Missing Link saga, and has a book coming out in August sure to touch on the topic. A lawsuit and a series of appeals funded by Ballard industrialists (the North Seattle Industrial Association often speaks as their collective voice) has delayed and forced the scaling back of a shovel-ready design the City has had since 2017, and squashed a supposed compromise clearing the way.

“People have been crashing on the train tracks consistently for decades as they try to navigate through industrial Ballard after the abrupt end of the Burke-Gilman Trail, and a group of eight injured riders filed a lawsuit against the city last year,” Fucoloro wrote. “There are many hazards in the Missing Link area, but the tracks under the Ballard Bridge are the worst. Many people have been seriously injured — left with everything from broken bones to head injuries — after crashing while trying to cross the tracks, which have wide and uneven gaps on either side of them that can surprise riders by grabbing their tires or otherwise knocking them off-balance.”

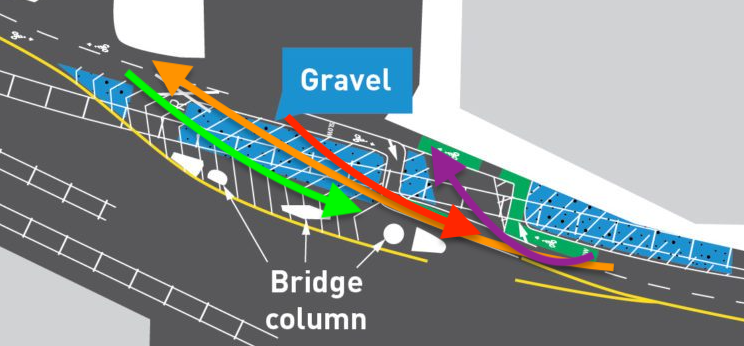

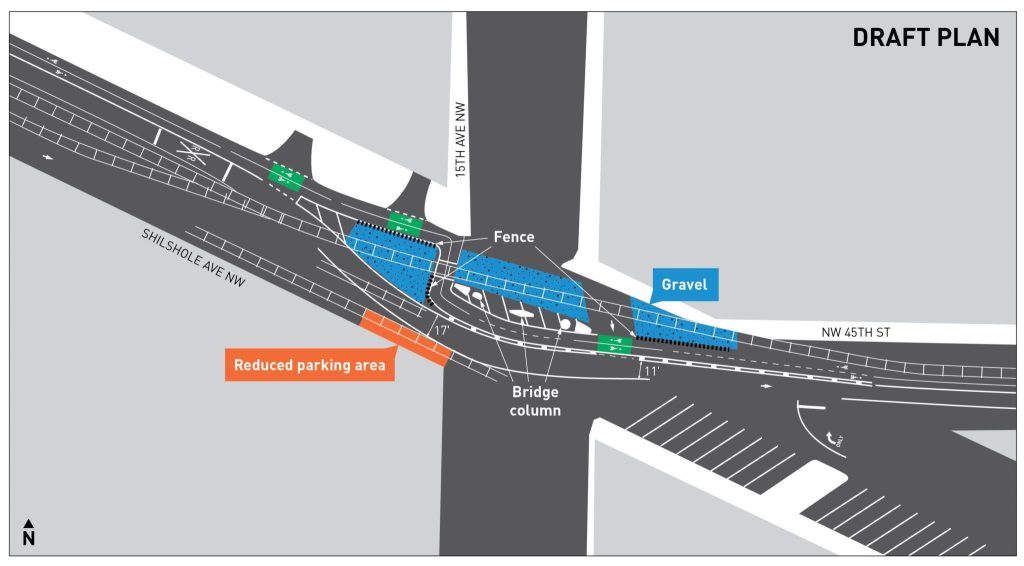

The intent of the gravel pits was to force people biking to cross the railroad tracks at a perpendicular angle or close to it. SDOT has further changes, such as fencing and a new crossing location, planned to reinforce that behavior. However, because SDOT designed a tight and awkward turn to cross the tracks, many people biking attempt to cross at different locations in order to avoid the slow, awkward pinchpoint or a potential collision with oncoming bike traffic navigating the hazard from the opposite direction.

In fact, around 80% of people biking through the stretch in Fucoloro’s 20 minutes of observation did not take the route SDOT is attempting to force them to take, instead taking a gentler turn through the area now consumed by gravel. The new design has likely led to some close calls and the loosely packed gravel is already deeply rutted with tire tracks, he reported. Fucoloro sketched the most common routes on the diagram below.

“As you can see, only the purple route avoided the gravel (this is also my suggested alternative in either direction if you can’t make the city’s sharp turns,” Fucoloro wrote. “Everyone else ended up riding through at least a little gravel, and a surprising number of people rode significant distances through the middle of the pit. I suspect this is the route they were used to riding before the gravel pits were dug out. I talked to several riders and asked them what they thought of the gravel, and they all absolutely hated it. Words were not minced.”

Observing for 15 minutes over the lunch hour, The Urbanist today found closer to a 50-50 split of people taking SDOT’s intended route or an alternative, which may be a reflection of the orange traffic cones helping to raise awareness of the marked crossing zone or repeat customers having enough experience with the gravel to know to avoid it. Some who did take the gravel route had fat tires and didn’t seem to have any trouble with the route. Small amounts of gravel had spilled out of the pits, but the bike lanes were generally clear during the visit.

“Safety is our top priority, and we are continuing to work to make it more intuitive for bike riders to navigate across these railroad tracks at the appropriate angle,” an SDOT spokesperson said. “As we continue to work to build additional safety enhancements, we encourage bike riders to keep in mind that the goal of these changes is to encourage people to slow down and stay safe when approaching the train tracks.”

Separating the marked turns for each direction of the bike lane to different sections of the track rather than the prior side-by-side arrangement does seem like an improvement that will come in especially handy as traffic picks up in summer months. On warm sunny days the Missing Link can be very busy. However, Phase Two of the changes will revise the alignment to again be side-by-side turns.

Bike education and forgiving designs

Due to the sorry state of transportation education in the United States, many people biking do not receive formal training in how to navigate railroad tracks. Many end up learning through trial and error — and hope the price for their first mistake is not too steep. Crashes occur because bike tires get sucked into the grooves next to rail tracks, which causes a sudden stall or change of direction that can send riders careening out of the saddle.

Avoiding crossing tracks at too shallow of angle is the first key to staying upright. A fully perpendicular route is not essential, but shallower that 45 degrees starts to get dicey, especially when riders don’t follow a second bit of advice: When crossing tracks stay balanced over the bike and do not change direction while over the hazard. Railroad tracks (and other slippery obstacles like ramps or gutters covered in leaves) become especially slippery when wet and initiating a turn while on them can lead to wipeouts.

Even the most seasoned and trained bicyclist can have a lapse of concentration which is why streets must be designed to allow for mistakes and prevent unnecessary hazards. Unfortunately, this stretch of trail in Ballard was never designed to be forgiving.

The Urbanist reached out to Bob Anderton, founding attorney at Washington Bike Law, which represents the litigants injured biking across the tracks that won the settlement with the City to Seattle to force a safer design at the spot.

“I am indeed concerned about the current condition of the Missing Link’s Crash Zone,” Anderton said in an email. “What I really want is for this area to be made reasonably safe for bicycle travel but that requires that the City complete all of its agreed changes in the Missing Link’s Crash Zone.”

Anderton has a long history representing the many people injured biking through the Missing Link.

“Washington Bike Law began litigating on behalf of people injured in the Missing Link’s Crash Zone in 2003,” Anderton added. “While there have been many plans to complete the Burke-Gilman Trail over the decades, the trail remains incomplete, and people keep regularly crashing on the railroad tracks there. Ultimately, if/when this area becomes part of the Burke-Gilman Trail, it should become much safer, but in the meantime, the City had — and still has — a duty to make the area reasonably safe for ordinary travel… and ordinary travel includes travel by bicycle.”

As The Urbanist reported in February, a recent settlement negotiated by Washington Bike Law has forced the City to implement a safer design immediately rather than waiting for the grand design of a full Missing Link fix, which again has been tied up it litigation for many years due to the endless string of appeals brought by neighboring industrial businesses. While Washington Bike Law said they didn’t ask for the unfenced gravel, SDOT argued they’re just following the settlement.

“We are required to build this project in this specific way and timeline due to a binding settlement agreement [pdf] with plaintiffs in the Robinson v. City and Ballard Terminal Railroad (the legal case described in this Urbanist article published last year),” the SDOT spokesperson continued. “The project will be built in two phases, as described in this blog post. Please note that this is a separate project from [Missing Link] work described on this webpage.”

Anderton noted those designs will be enforceable due to the settlement.

“In the most recent litigation, Washington Bike Law’s clients obtained not just insurance money to make up for the harm done to them as individuals, but as part of the settlement they obtained an enforceable agreement from the City of Seattle with deadlines to make specific changes to the Missing Link with the goal of making it safer for everyone,” Anderton said. “This agreement was signed on behalf of the City of Seattle on December 20, 2022 and includes illustrations of the agreed changes to come.”

A look at Phase Two

While Anderton seemed disappointed by the latest changes to the “crash zone,” he said the next phases of changes should rectify the issues.

“I am not a traffic engineer, but I am a person who rides a bike pretty much every day, and anyone who rides a bike knows that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to make extremely sharp turns like those currently on the Missing Link Crash Zone,” Anderton said. “Thankfully, this is only the initial step of the City’s agreed changes. The City has also agreed to increase the space for riders to turn to cross the railroad tracks and add fencing to keep riders off the gravel and the gravel out of the bike lanes.”

The settlement gives the city until the end of 2023 to finish Phase Two of the redesign and add the fencing, which limits legal recourse in the near-term.

“Unfortunately, the agreement gives the City until December 31, 2023 to complete Phase Two,” Anderton said. “It is my sincere hope that the City will complete all of its agreed work much sooner than that, but Washington Bike Law will not have the power to enforce our agreement with the City regarding the completion of Phase Two until 2024.”

An SDOT spokesperson said they intended to follow up with Phase Two once the dry season returns but didn’t pledge any earlier deadlines for the work.

“Building the next phase involves paving work which requires predictable dry weather. We plan to prioritize scheduling this once sunnier weather arrives,” an SDOT spokesperson said. “In the meantime, we will have street cleaning crews visit the site to manage the gravel that gets into the bike lane.”

This is but the latest frustration for people biking the Missing Link, but Anderton saw a light at the end of the tunnel: “While December 31, 2023 may seem like a long time from now, in the context of decades of people regularly crashing on the Missing Link and the many plans to complete the Burke-Gilman Trail through Ballard but few actions to make the street reasonably safe, it is at least a date by which this known danger to people riding bicycles should be made safer.”

Hope for a full fix to the Missing Link

Meanwhile, the legal wrangling continues to complete the entire 1.4-mile Missing Link of the Burke-Gilman. It is unclear how soon the lawsuits can be dispatched with to clear the way for construction. SDOT’s project webpage still imagines Shilshole Avenue construction will start this summer, but that appears wishful thinking without legal challenges cleared. Some politicians have proposed switching to a different route, such as Leary Way NW, to circumvent the legal block, but political or legal obstacles could arise for those routes, too.

“Ultimately, we want to see the Burke-Gilman Trail completed, but until then, it needs to be made safer,” Anderton said in a comment thread on the Seattle Bike Blog. “This is the first step.”

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.