A primer on the four horsemen of sprawl – zoning, subdivision, covenants, and mortgages.

There is good news coming out of legislatures and city councils. Housing is on everyone’s mind, and abundance is the keyword. Many jurisdictions and the State of Washington are considering lifting restrictions on density and increasing housing choice in a broad variety of neighborhoods.

Unfortunately, many of these changes are happening at just the level of zoning. Make no mistake, zoning reform is a very big deal and a vital change if we are to overcome the housing affordability crisis and meet our climate goals. Zoning is a huge impediment to missing middle housing, but it evolved parallel to three other land use controls.

Zoning is the shape of the building, its use, and its placement on a property. The shape of the property is determined by a plat that is developed through the city’s subdivision rules. Conveying the property is done through deeds, which often carry covenants that restrict the use and look of buildings. And few can get their own deed without a mortgage. Those are the four legs of our housing table – zoning, subdivision, covenants, and mortgages.

For almost a century, these four legs have worked together to build a massive amount of single family detached, car-dependent houses on cheap land outside of cities. For at least 40 years, the mechanism has been in overdrive. Even if zoning gets fixed and stops dictating sprawl, here is how the other three parts reinforce private, separated houses.

Subdivision for separate lots and parking

The purpose of subdivision is to carve buildable, sellable lots out of larger properties. To do that, cities have to follow arcane state rules dictating how the shape of the property impacts the health, safety, and welfare of the community. This includes making sure there are connections to utilities and streets, as well as adequate fire and police services. Subdivision approval concludes by writing these requirements permanently into a plat that is filed in the land record.

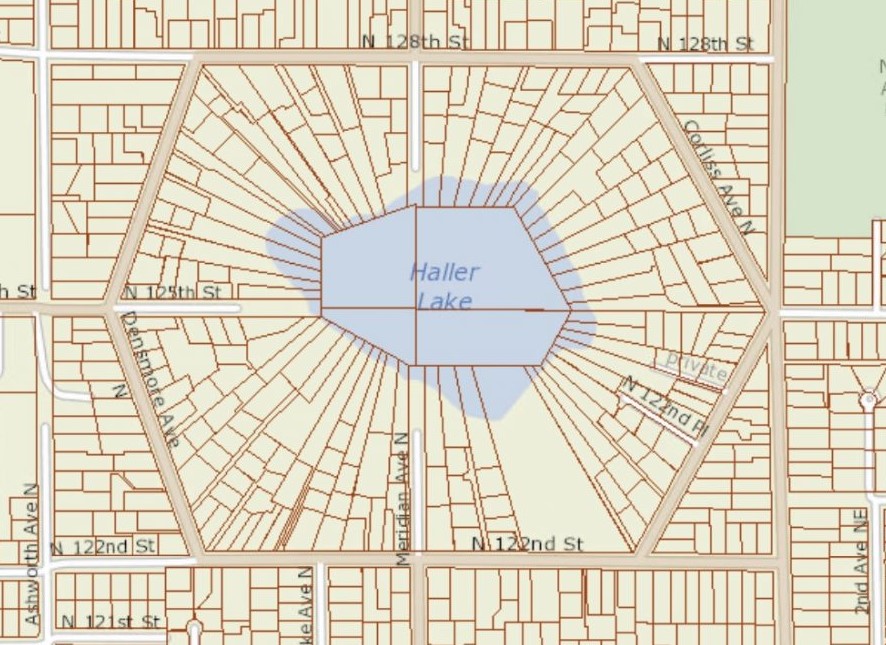

Subdivision reinforces individual homes in two ways. First, subdivision is specifically designed to create separate lots for sale. As we have covered, subdivision is a process that shreds the land into tiny pieces that will not reassemble for the life of these buildings, just for the purpose of attaching a single house to its own chunk of ground. They may be attached townhouses, but the land underneath is carved out from all others and adds a massive expense to the house. Other attached units like condominiums fall under a completely different provision of state law.

Second, all of the concepts of “adequate” in subdivision rest on that separation. The infrastructure must be in place for each lot to be served individually. For example, the Seattle code requires “vehicular access to every lot shall be from a dedicated street.” Exceptions can be granted, but they are exceptions and only granted if a check down list of items are met. The result is asphalt everywhere and bizarre lots just to support driveways.

The art of the Covenant

Everyone gets hot and bothered about the idea of homeowners associations and many of us take pleasure in the stories of people sticking it to their overbearing homeowners association (HOA). But such non-profit associations arise for very specific purposes. When a large lot is subdivided, there are often community spaces or private streets that need an entity to own them. This is the case in the appalling, climate destroying design for McMansions at Talaris. Tying the HOA to the individual properties and the individual properties to one another are deed restrictions called covenants, or agreements to refrain from an action or change.

Covenants have a very bad name because many arose due to racism. Racially restrictive covenants prevented Black, Jewish, Indigenous, and Asian-descended people from living in new housing all over Seattle. As noted here before, the local paper spent years profiting from advertisements touting euphemistically “deed restricted” developments.

Sometimes those racial restrictions were established in the same breath with land use controls. For example, in Quigley’s Northend Tracts, the restriction reads: “The property covered by this contract shall not be conveyed to any other than one of the Caucasian race; that no building shall be closer than twenty (20) feet from the property line, facing any street. The property covered by this contract is to be used for residence purposes only.”

Racial restrictions are no longer enforceable, and Washington provides a process for having them nullified in the deeds. However, the restrictions on uses and maintaining setbacks are perfectly legal and allowed to continue. Indeed, even groups of townhomes that never had an HOA often have deed restrictions and covenants because they share a driveway across those weird lots.

Mortgages for predictable banking

Even getting to those deeds depends on financing property through a system that affirms local zoning and subdivision. The most affordable mortgages are conventional conforming loans. Such loans go through a conventional bank and conform to the limits set up by the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA). If a bank writes a conforming mortgage, they can then turn around and sell that loan to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — the federal mortgage loan companies. The bank can then use the money they receive to write more loans. Conventional loans keep cash moving in the economy, so they are cheap and ubiquitous.

Though they are not zoning, mortgages control the size and shape of buildings. Like we have mentioned here before, conventional conforming loans have FHFA limits that directly oppose missing middle housing. Mortgages cannot be used for buildings with more than four units, and banks often separately limit themselves to writing loans for singles or duplexes only. The value of loans is capped, with increases for units three and four that do not pace with the increase in cost to buy. Purchasers cannot use projected rental income from other units in qualifying for the loans.

More broadly, these are limits on the purchase of an existing building. Separate loans may be necessary to build missing middle homes, instruments that are not readily available to the average person. Financing may be theoretically available to construct an owner-occupied six-plex. But the unique loan documents and higher interest rates are yet another expense that ends up being a regulatory bar to denser housing.

The horsemen ride together

The hard truth is that all of these components lean against one another. Documents reference one another, with covenants showing up in plats then recorded in mortgages. Regulations bless each other, with zoning recognizing deed restrictions and HOAs. And they all evolved together.

Some handshakes are written in law outright. Revised Code of Washington (RCW) 58.17.195 reinforces zoning in the subdivision text, stating “No plat or short plat may be approved unless the city, town, or county makes a formal written finding of fact that the proposed subdivision or proposed short subdivision is in conformity with any applicable zoning ordinance or other land use controls which may exist.” Or Seattle’s subdivision code allows the hearing examiner to waive dedication of public land for streets, but specifies that land “be conveyed to a homeowner’s nonprofit maintenance corporation.” Fannie Mae only purchases mortgages on properties that the house is the “legal conforming use of the land” and avoids properties with wetland or coastal land use designations.

Other provisions sound like an allowance, but end up reinforcing the harshest lines. The exceptions to accessing a dedicated street mentioned above rely on HOAs and covenants. RCW 58.17.217 provides for alteration of a subdivision with consent of a majority of owners, unless it is covered by a covenant which requires all subject parties approve. That is often the whole subdivision.

Now this all may sound dire, but in no way is it trying to dissuade attempts to fix zoning. What we have is more of a to-do list so that exciting new concepts can actually work. Zoning reform must recognize the whole apparatus of land use and deeds and financing that have spent a century growing together. A new zoning idea must also be able to be written into a plat, overcome covenant restrictions, and find financing. These things are absolutely possible, so long as we recognize they’re necessary.

More importantly, this is a call to try everything. The monolith of intertwined land use controls seems insurmountable now, but if we consider the last century, none of them were certain. Zoning continually gets expanded, litigated, and adapted. A third of the rules in subdivision and property law are about what to do to correct an improperly wild deed or incomplete plat. And the litany of financial debacles moves backwards from subprime mortgages through Savings and Loans to It’s a Wonderful Life. Zoning, subdivision, covenants, and mortgages evolved together because they individually had to evolve.

It is time for them to evolve again.

Ray Dubicki is a stay-at-home dad and parent-on-call for taking care of general school and neighborhood tasks around Ballard. This lets him see how urbanism works (or doesn’t) during the hours most people are locked in their office. He is an attorney and urbanist by training, with soup-to-nuts planning experience from code enforcement to university development to writing zoning ordinances. He enjoys using PowerPoint, but only because it’s no longer a weekly obligation.