It has been raining housing reports and housing news over the last week. Challenge Seattle, an alliance of local CEOs, released a 124-page housing report last Thursday that makes the case for Washington State cities to overhaul their zoning, land use, and permitting policies. The same day, Urban Institute released a lengthy housing, which The Urbanist covered. Released on the eve of the start of session for the Washington State Legislature, both reports build the case for state lawmakers to take bold actions to promote housing creation in cities statewide.

The Seattle City Council meeting this Tuesday also became an unexpected flashpoint in the battle between housing advocates and historic preservationists. The historic preservationists won this round. In a 7-2 vote, councilmembers rejected a proposal from Councilmember Tammy Morales to lift historic landmark development controls on a one-story Walgreens drive thru on the edge of South Lake Union, instead opting to preserve the building. Morales’ bill would have cleared a path to building a 16-story residential tower on the site with fewer hurdles. (Author’s note: I penned an op-ed and submitted public testimony in favor of redeveloping the entire site rather than treating as sacrosanct a non-descript old drive-thru bank turned Walgreens.)

More on that after digging into the Challenge Seattle report.

Challenge Seattle signals support for aggressive zoning reform

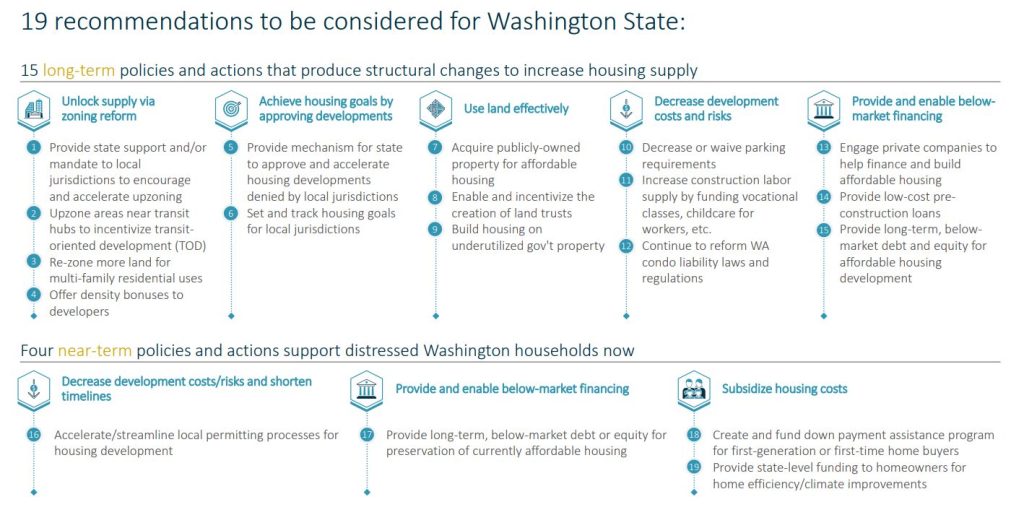

Zoning reform has already earned strong backing from urbanists, housing advocates, and organized labor. In addition to translating several broad policy suggestions to a more granular level, the Challenge Seattle report signals that business leaders support this zoning push, as well.

“The solution to the housing affordability crisis starts with zoning,” Challenge Seattle writes in first takeaway of the executive summary. “Zoning reform is the critical enabler for removing regulatory barriers standing in the way of the private market producing more housing units. In the context of Washington, we would need to change zoning laws to allow for more density and re-zone more land for multi-family residential uses.”

A statewide zoning policy could have huge implications for housing supply, the reports notes, pointing to California’s recent reforms to allow housing on commercial corridors.

“On Zoning: >90% of Mercer Island and >70% of Seattle and Bellevue are zoned as single-family,” the executive summary continues. “Up-zoning these areas will unlock a significant amount of housing supply. To the south, California recently passed Senate Bill 6 authorizing residential housing projects in commercial corridors otherwise zoned for large retail and office buildings; by some estimates, this new law could produce up to 2.4 million new units.”

The report also recommends waiving parking requirements (which add considerably to housing costs) and accelerating and streamlining local permitting processes for housing development. One bill at the state legislature (HB 1026) seeks to tackle the design review reform question, but getting the specifics right will be crucial in order to actually shorten timelines and reduce permitting uncertainty.

An earlier report from Challenge Seattle had been a bit more pessimistic about the prospects of zoning reform and building enough in-fill housing in existing cities, instead arguing for brand new “hub cities” built from scratch along a new high speed rail line in the I-5 corridor. The new report may have heard the criticism and seems more focused on working within existing built urban environments.

Deeper into the appendices, the new report walks through those hypothetical developer scenarios (or pro formas, in development industry lingo) that seek to show the cost of various regulatory policies, such as parking requirements and impact fees, which is recommends decreasing or waiving. As a more centrist take on policy, the report is skeptical of rent control or stabilization policies, trying to dispatch it with traditional classical economics arguments (some of which subsequent research has cast doubt on).

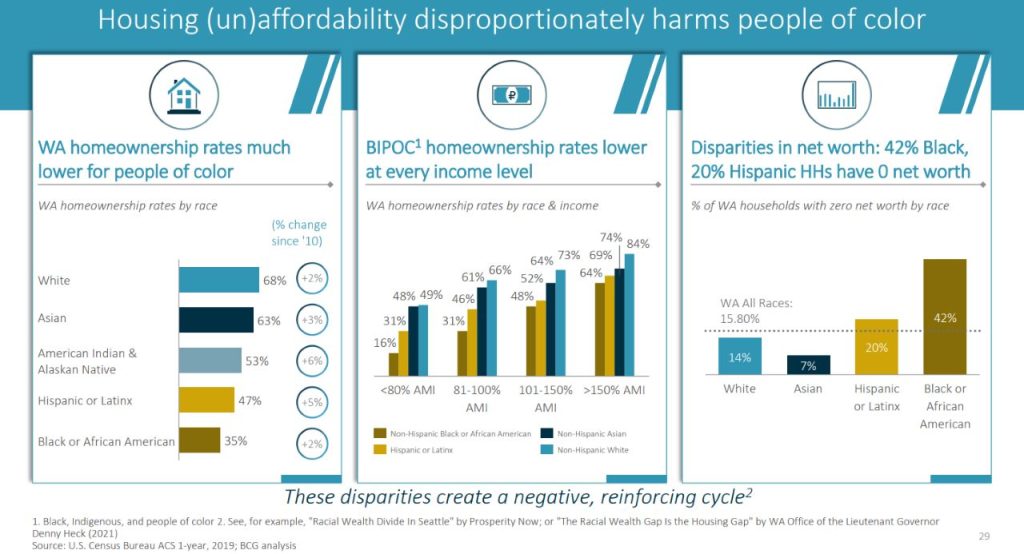

On the other hand, the report underscores the negative impact the housing crisis has on communities of color, who are much less likely to own their homes and miss the benefit of rapidly appreciating prices.

All in all, the added voice in the chorus calling for statewide zoning reform is a welcome development to the Homes for WA coalition.

Seattle Council chooses preservation over transit-oriented development

Councilmember Tammy Morales’ proposal to fully removing historic landmark status of Walgreens on Denny Way was blocked by an amendment from Councilmember Lisa Herbold that does allow a nearly 12,000-square-foot parking lot on the site to be redeveloped. A further amendment from Councilmember Andrew Lewis also removed development controls on the drive thru driveway and the signage on the site, hypothetically adding space for another 30 homes or so. Thus, a smaller redevelopment project will still be possible on the site, but the building itself will continue to face development controls via its continued landmark status.

Morales expressed her disappointment in the vote, in which only Councilmember Teresa Mosqueda joined her in opposing Herbold’s substitute amendment.

“We are in a housing crisis,” Morales said in a tweet. “While I’ve passed every piece of landmark legislation that’s come before my committee, it’s not good policy to sacrifice the potential for hundreds of homes in the densest neighborhood in Washington State to protect a Walgreens.”

The site is adjacent to the RapidRide E Line, the region’s busiest bus, and will be a few blocks of a light rail station once Ballard Link is built.

While arguing against Herbold’s amendment, Mosqueda noted that Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) contributions — which amount to about $3.5 million in a full buildout of zoned capacity — would also be jeopardized or reduced by imposing the controls, cut nearly in half if a project were to materialize at all.

Councilmembers had a difference of opinions about how big of a drag the landmark development controls would be on the building. Herbold, echoing historic preservationists who called in to testify at the meeting, argued that imposing landmark controls on the building but developing the parking lot would actually result in more housing via a transfer of development rights arrangement. Herbold’s math appeared to switch from full-sized units — including some multi-bedroom apartments — to micro-apartments of about 300 square feet in size to make the unit numbers work.

Actual developers and development professionals were skeptical that such a scenario would actually play out in practice. In fact, land use attorney Jessica Clawson said that a tower would not be buildable with the landmark controls in place because the tower would be too skinny to efficiently use the space and thus wouldn’t “pencil out” as profitable.

Councilmembers Dan Strauss and Sara Nelson seemed to be swayed by Herbold’s arguments, and also stressed the need to balance housing needs with proper process and historic preservation needs. Lewis and Strauss said they wouldn’t have supported Herbold’s amendment without Lewis’ additional amendment layered on top of it, which passed unanimously.

Councilmember Kshama Sawant, though a staunch socialist, supported the vote to preserve the historic drive-thru bank built in 1950. She laid out her own unique case for doing so, arguing that market-rate development isn’t part of the solution and doesn’t matter to Seattle’s housing affordability crisis and that the council should bow to the landmarks board and focus on building social housing.

Original sponsor Morales has also been outspoken in favor of social housing, and pushed unsuccessfully for an amendment funding a new social housing team at the Office of Housing in the last budget cycle. She had a different take on historic preservation, however. Social housing built on the site would be equally constrained by landmark controls, and the larger battle about how wide of a net to cast when preserving old buildings could impact many potential social housing sites down the road.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.